|

An Audiovisual Intervention’s

Effects on Psychological Barriers toward initiating

Insulin Therapy among diabetic type 2 patients:

A randomized controlled trial

Faisal Jammah

S Alghamdi

(1)

Mazen Ferwana

(2)

Mohammed Fahad Alsaif

(1)

Fahad Nasser Algahtani

(1)

Emad Masuadi (1)

(1) College of Medicine, King Saud Bin Abdulaziz

University (KSAU-HS), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

(2) Consultant & Trainer, Family Medicine,

King Abdulaziz Medical City, NGHA, Professor,

King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health

Sciences, Co-Director, National & Gulf Center

for Evidence Based Health Practice

Correspondence:

Faisal Jammah S Alghamdi, MBBS

Medical Intern, College of Medicine, KSAU-HS

P.O. Box 22490, Riyadh 11426, Saudi Arabia

Tel: +966566367778

Email: fj.gh@outlook.com

Received: November 2018; Accepted: December

2018; Published: January 1, 2019

Citation: Faisal Jammah S Alghamdi, Mazen Ferwana,

Mohammed Fahad Alsaif, Fahad Nasser Algahtani,

Emad Masuadi. An Audiovisual Intervention’s

Effects on Psychological Barriers toward initiating

Insulin Therapy among diabetic type 2 patients:

A randomized controlled trial. World Family

Medicine. 2019; 17(1): 29-35.DOI: 10.5742MEWFM.2019.93596

|

Abstract

Introduction: This study evaluates

the effectiveness of educational videos

against patients’ fixed beliefs and

lack of knowledge in comparison with traditional

educational methods. It investigates the

effectiveness of these tools in overcoming

patients’ psychological barriers

toward insulin therapy.

Methods: This

randomized, controlled trial used the

validated insulin treatment appraisal

scale (ITAS) to evaluate patients’

psychological barriers. An educational

video and brochure were developed, each

containing the same contents. The study

was conducted in King Abdulaziz city housing

with a total sample size of 126, divided

into an intervention group (who were shown

the video) and a control group (who were

given the brochure). Both groups filled

out the same questionnaire before the

intervention, immediately after the intervention,

and six weeks later.

Results:

Neither educational method showed superiority

to the other. Most of the questionnaire

items had a nonsignificant p-value for

both methods, and even when one intervention

method was effective, the other method

showed similar effectiveness.

Conclusion:

This study showed no superiority of

the video over the brochure, which cost

less and required less effort to produce.

Trial registration

number: NCT03544645

Key words:

audiovisual; diabetes type 2; educational

intervention; insulin therapy; psychological

insulin barriers.

|

Insulin should be prescribed more frequently

among type 2 diabetic patients, especially when

oral medications alone are not effective anymore

[1]. Despite being the most effective diabetes

treatment, patients often feel reluctant to

initiate insulin therapy when it is needed.

Many studies relate this reluctance to reasons

such as fear of disease progression, needle

anxiety, feelings of guilt and failure, concerns

about hypoglycemia, sense of loss of control

over one’s life, reduced quality of life,

and the fear of being stigmatized [1-7]. All

these reasons have contributed to the prevalence

of uncontrolled diabetes; a survey conducted

in the USA showed that the percentage of controlled

diabetic patients was only 36% [8], and a 2012

study in the Al Hassa region of Saudi Arabia

showed that the percentage of uncontrolled diabetic

patients was 69% [9].

The impact of most of these reasons are overestimated

by patients and can be overcome with an insulin

analogue and a new delivery method. For example,

a novo pen, which many studies have found to

be less painful, is easier to carry around than

traditional delivery methods and leads to less

hypoglycemic events [10-12]. The fact that patients

still so frequently cite the reasons above indicates

that up-to-date methods are not being provided

to patients, which could be accomplished through

traditional educational methods such as brochures,

leaflets, or face-to-face discussions [13].

A newer educational technology is educational

videos, and many studies emphasize the effectiveness

of this method [14-18]. In one study, a video-based

lifestyle educational trial was designed for

newly diagnosed type 2 diabetics, who were divided

into a video education group and a control group.

The video education group showed more improvement

in general knowledge related to lifestyle than

the control group [14]. Another study about

heart failure patients revealed that patients

who received video education showed less signs

and symptoms of heart failure, such as edema,

fatigue, and dyspnea, than another group that

received only traditional education [15]. Even

if we compare video education with other newer

methods such as internet research, video education

is more effective because patients are more

likely to review all the information provided

to them [16]. In addition, another study found

that video intervention was one of the best

methods to increase the knowledge of health

issues, such as certain disease complications,

in people with low literacy [17].

Furthermore, a systematic review that included

40 studies related to video intervention showed

how video education was effective in three major

ways: supporting the treatment decision, reducing

anxiety, and supporting coping skills to increase

self-care practices [18]. Since there have been

no previous studies comparing the difference

in effects between traditional and non-traditional

education methods on diabetic patients’

attitudes in Saudi Arabia, this study aims to

compare the impact of audiovisual educational

materials versus printed educational materials

on type 2 diabetic patients’ knowledge,

attitudes, and practices towards insulin therapy.

It does so by assessing the patients before,

immediately after, and 6 weeks after the intervention.

We conducted a randomized controlled trial

on type 2 diabetic patients who agreed to participate

in the study after screening them for inclusion

and exclusion criteria. The target population

of the study was type 2 diabetic patients who

had an A1c of 8 mg/dL or above, were aged 30

to 70 years, and had not yet begun insulin therapy.

Patients currently experiencing pregnancy, blindness,

profound vision loss, or severe mental problems

such as psychosis were excluded.

The study was conducted from March to June

2017 in a community-based polyclinic located

in the King Abdulaziz city housing for the National

Guard in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This polyclinic

includes primary care centers and serves about

60,000 individuals, consisting of soldiers and

their families as well as the professionals

who work there and their families. We developed

an educational video and brochure, both of which

contained the same content about knowledge,

attitude, behavior, and psychological barriers

toward insulin therapy. The intervention group

was shown the educational video and the control

group was given the brochure. Both groups filled

out a questionnaire before the intervention,

then immediately after the intervention filled

out the same questionnaire to assess the materials’

immediate effects. Six weeks later, both groups

filled out the same questionnaire once more

to measure the long-term effects. The immediate

and long-term effects of both groups were compared

to assess the materials’ effects on participants’

knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and psychological

barriers toward insulin therapy.

A computerized sequence in Microsoft Excel

2016 generated a randomized list of patients,

allocating participants into 2 groups: an audiovisual

intervention group and a printed material control

group. A serially numbered opaque sealed envelope

(SNOSE) contained these group assignments. The

total sample size was 126 patients (63 in each

group), which afforded us an 80% power to detect

a difference of at least 5% in the mean knowledge

percentage between the two groups, with an equal

standard deviation of 10% and a significance

level () of 5% using two proportions (z-test).

The validated insulin treatment appraisal scale

(ITAS) questionnaire was used [19]. It is available

on the internet free of charge, and permission

to use it was obtained. The questionnaire measured

the following variables: attitude, knowledge,

practice, and behavior. It was translated into

Arabic and pre-tested.

The educational video, which we developed and

validated for this study and presented to the

intervention group, aimed to address the psychological

barriers mentioned in the questionnaire and

tried to correct patients’

misconceptions about insulin therapy. More specifically,

it aimed to overcome the barriers by briefly explaining

the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and the

ways to manage type 2 diabetes, focusing especially

on the advantages, adverse effects, and misconceptions

about insulin therapy. Its content was developed

based on the American Diabetes Association’s

2017 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes [20];

the validation process included family physicians

to ensure that the content was appropriate for

the patients and medical students to ensure the

quality of the design and avoid any language mistakes;

it also included type 2 diabetic patients with

similar inclusion and exclusion criteria of this

study to ensure that the video is suitable for

them in terms of language and approach. The validation

paper has been published separately (27), and

the video with English subtitles can be accessed

from the link in the reference list [21].For each

item on the questionnaire, two p-values were measured.

The first was obtained with McNemar’s test,

to measure the effect of each intervention individually.

The second was obtained using a two-proportion

z-test to compare the two interventions and determine

if either was superior. Results with a p <

0.05 were considered significant. IBM SPSS Statistics

20, manufactured by IBM Corp., was used for data

analysis.

Ethics

This study was sponsored and ethically approved

by King Abdullah International Medical Research

Center’s (KAIMRC) ethic committee with

ID number (SP16/235), and all patients provided

written consent. It was also registered in the

trial registry, clinicaltrial.gov, with a trial

registration number of NCT03544645.

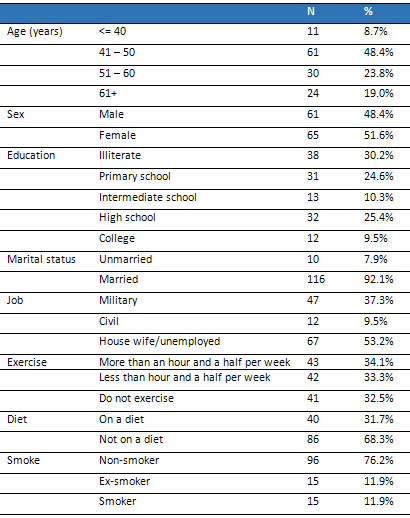

The study included 126 diabetic patients, with

no losses during the study. Patients’ demographics

are presented in Table 1. Table 2 shows the

effects of the two intervention methods (the

video and the brochure) regarding patients’

fixed beliefs, namely their psychological barriers

to insulin therapy (determined through 10 questions),

and regarding their understanding of insulin

therapy as the ideal treatment for their condition

(2 questions, q6 and q7, in Table 2). The percentages

in Table 2 represent the participants who agreed

with the questions’ statements, and each

question had 3 main p-values: one for the effect

of the video, one for the effect of the brochure,

and the last to show any superiority in method,

whether it was for the video or the brochure.

The different p-values measure the reductions

in barriers between before and immediately after

the intervention, as well as the reduction between

before and 6 weeks after the intervention.

As determined by McNemar’s test, the questions

related to the psychological barriers to insulin

therapy (questions 1 and 3: “I am worried

about starting insulin therapy” and “Taking

insulin means my health will deteriorate”)

showed significant p-values (<0.05) for both

the video and the brochure. Interestingly, questions

11 and 12 (“Taking insulin increases the

risk of low blood glucose levels” and “Insulin

causes weight gain”) showed positive p-values

for both the brochure and video, but the reductions

were of negative value and, since the question

was not a negative statement, these values were

significant for their reverse outcomes. A reverse

outcome here means that instead of decreasing

the barriers, the intervention methods increased

them , although these barriers were addressed

directly with both methods.

There were no significant p-values for the

other barriers related to insulin therapy, indicating

that neither intervention was effective in this

regard. However, q6 and q7 (“Taking insulin

helps to prevent complications of diabetes”

and “Taking insulin helps to improve my

health,” respectively), which were related

to the benefits of insulin but not psychological

barriers toward insulin therapy, showed significant

p-values for both interventions.

As for the two-proportion z-tests used to compare

the two interventions, most p-values were non-significant.

That is, even when the video showed effectiveness,

the brochure showed an equal effect; thus, neither

method appeared superior to the other.

Table 1: Participants’

Demographics

Click here for Table

2: Questionnaire Items

Although both interventions had a slight effect,

it was still not large enough to alter patients’

fixed beliefs and behaviors. The interventions

reinforced the positive ideas patients already

had about the benefits of insulin therapy, but

were not sufficient to break their psychological

barriers to insulin therapy, such as feelings

of guilt and failure, fear of disease progression,

feelings of a loss of control over one’s

life, and the fear of being stigmatized, even

though both intervention methods addressed these

beliefs directly. In fact, patients’ worries

about hypoglycemic attacks and weight gain increased

at the mere mention of them in the interventions,

even though the interventions indicated that

new methods could help overcome these problems.

Overall, neither method was found to be superior.

A meta-analysis has shown that video interventions

are effective in some settings such as breast

self-examination, prostate cancer screening,

sunscreen adherence, self-care in patients with

heart failure, and HIV testing and treatment

adherence [22]. However, this study shows that

such an intervention is not effective in changing

overall behaviors or attitudes, nor fixed beliefs

toward insulin therapy, such as psychological

barriers. Thus, the intervention’s goal

plays an important role in its impact.

The result of this study raises the question

of whether multifaceted intervention could be

more effective than one-method intervention.

One study that targeted diabetic patients with

multifaceted interventions, such as problem-based

learning sessions and educator-patient face-to-face

sessions, showed improvements in their A1C and

blood pressure [23]. In addition, two studies

on multifaceted interventions showed improvements

in drug adherence for post ACS and anti-depressant

drugs using booklets, voice messages, and counseling

interventions [24-25].

The present study had several limitations and

strengths. The limitations included a sample

limited to a clinic located in housing for National

Guard soldiers, which may not represent the

population of Riyadh as a whole. The strengths

include the study’s randomized approach,

which helped minimize bias, as well as the high

response rate, strict inclusion criteria, the

consistency of the research method, the follow-up

after six weeks, and and the fact that the educational

video was validated by the authors of this study.

Audiovisual methods such as educational

videos are important sources for delivering

different kinds of information. This

study demonstrates that these methods

can be useful for delivering new information

and increasing people’s general

knowledge, but sometimes fall short

in changing people’s pre-existing

fixed beliefs, such as psychological

barriers regarding insulin therapy.

The results of the study raise the question

of whether educational materials are

indeed superior to doctor–patient

educational sessions, which are more

interactive and allow the patient to

ask questions. It also suggests that

a multifaceted intervention could be

more effective than a one-method intervention.

Future research should consider what

further efforts are required to change

misleading information that people believe.

Determining what new technologies should

be utilized as intervention methods

is a wide research field with a promising

future. One such technology is social

media, which is now widely accepted

and has many active users. One study

has demonstrated that social media can

be effective as an intervention method

to increase patients’ physical

activity [26], but further research

on this subject is lacking.

Funding source: The research

was supported by King Abdullah International

Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) [Grant

Number: SP16\235]. The funder had no

role in study design; in the collection,

analysis and interpretation of data;

in the writing of the report, and in

the decision to submit the article for

publication.

Acknowledgments: We give special

thanks to the National Guard Health

Affair department and College of Medicine,

as well as King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University

for Health Science, for their consultations

and the permission to use their faculties.

We would also like to thank Editage

(www.editage.com) for English language

editing.

1. Edelman S, Pettus J. Challenges associated

with insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes

mellitus. Am. J. Med. 2014;127:S11–6.

2. Bogatean MP, Hâncu N. People

with type 2 diabetes facing the reality

of starting insulin therapy: factors involved

in psychological insulin resistance. Pract.

Diabetes Int. 2004;21:247–52.

3. Korytkowski M. When oral agents fail:

practical barriers to starting insulin.

Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2002;26

Suppl 3:S18–24.

4. Funnell MM. Overcoming barriers to

the initiation of insulin therapy. Clin.

Diabetes. 2007;25:36–38.

5. Davis SN, Renda SM. Psychological insulin

resistance: overcoming barriers to starting

insulin therapy. Diabetes Educ. 2006;

32 Suppl 4:146S–52S.

6. Peragallo-Dittko V. Removing barriers

to insulin therapy. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33

Suppl 3:60S–5S.

7. Brod M, Kongsø JH, Lessard S,

Christensen TL. Psychological insulin

resistance: patient beliefs and implications

for diabetes management. Qual. Life Res.

2009;18:23–32.

8. Koro CE, Bowlin SJ, Bourgeois N, Fedder

DO. Glycemic control from 1988 to 2000

among U.S. adults diagnosed with type

2 diabetes: a preliminary report. Diabetes

Care. 2004;27:17–20.

9. Khan AR, Al-Abdul Lateef ZN, Al Aithan

MA, Bu-Khamseen MA, Al Ibrahim I, Khan

SA. Factors contributing to non-compliance

among diabetics attending primary health

centers in the Al Hasa district of Saudi

Arabia. J Fam Commun Med. 2012;19:26–32.

10. Kadiri A, Chraibi A, Marouan F et

al. Comparison of NovoPen 3 and syringes/vials

in the acceptance of insulin therapy in

NIDDM patients with secondary failure

to oral hypoglycaemic agents. Diabetes

Res. Clin. Pract. 1998;41:15–23.

11. Tschiedel B, Almeida O, Redfearn J,

Flacke F. Initial experience and evaluation

of reusable insulin pen devices among

patients with diabetes in emerging countries.

Diabetes Ther. 2014;5:545–55.

12. American Diabetes Association, Standards

of medical care in diabetes—2008.

Diabetes Care. 2008;31 Suppl 1:S12–54.

13. Khan MA, Shah S, Grudzien A et al.

A diabetes education multimedia program

in the waiting room setting. Diabetes

Ther. 2011;2:178–88.

14. Dyson PA, Beatty S, Matthews DR. An

assessment of lifestyle video education

for people newly diagnosed with type 2

diabetes. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23:353–59.

15. Albert NM, Buchsbaum R, Li J. Randomized

study of the effect of video education

on heart failure healthcare utilization,

symptoms, and self-care behaviors. Patient

Educ Couns. 2007;69:129–39.

16. Frosch DL, Kaplan RM, Felitti VJ.

A randomized controlled trial comparing

internet and video to facilitate patient

education for men considering the prostate

specific antigen test. J. Gen. Intern.

Med. 2003;18:781–87.

17. Gerber BS, Brodsky IG, Lawless KA

et al. Implementation and evaluation of

a low-literacy diabetes education computer

multimedia application. Diabetes Care.

2005;28:1574–80.

18. Krouse HJ. Video modelling to educate

patients. J Adv Nurs 2001;33:748–57.

19. Snoek F, Skovlund S, Pouwer F. Development

and validation of the insulin treatment

appraisal scale (ITAS) in patients with

type 2 diabetes. Health Qual Life Outcomes.

2007;5:69.

20. American Diabetes Association, 1.

Promoting health and reducing disparities

in populations. Diabetes Care. 2017; 40:S6–10.

21. Alsaif M. Patients’ barriers

towards insulin therapy 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ye9SRh59pjg&t=112s.

Accessed 16 Oct 2018

22. Tuong W, Larsen ER, Armstrong AW.

Videos to influence: a systematic review

of effectiveness of video-based education

in modifying health behaviors. J Behav

Med 2014;37:218–33.

23. Piatt GA, Anderson RM, Brooks MM et

al. 3-year follow-up of clinical and behavioral

improvements following a multifaceted

diabetes care intervention: results of

a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes

Educ. 2010;36:301–9.24. Ho PM, Lambert-Kerzner

A, Carey EP et al. Multifaceted intervention

to improve medication adherence and secondary

prevention measures after acute coronary

syndrome hospital discharge: a randomized

clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:186–93.

25. Katon WA, Robinson P, Von Korff M

et al . A Multifaceted intervention to

improve treatment of depression in primary

care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:924–32.

26. Zhang J, Brackbill D, Yang S, Centola

D. Identifying the effects of social media

on health behavior: data from a large-scale

online experiment. Data Brief. 2015;5:453–57.

27. Fahad Algahtani, Mazen Ferwana, Mohammad

Alsaif, Faisal Alghamdi. Validation of

Audiovisual Educational Tool that discusses

psychological insulin barriers for type

2 diabetic patients. World Family Medicine.

2019; 17(1): 23-28.DOI: 10.5742MEWFM.2019.93595

|