|

Suicide pattern in Kermanshah

Province, West of Iran:

March 2012- March 2013

Mehran Rostami

(1)

Abdollah Jalilian (2)

Ramin Rezaei-Zangeneh (3)

Teimour Jamshidi (4)

Mohsen Rezaeian (5,6)

(1) Mehran Rostami (MSc); Deputy for Treatment,

Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah,

Iran

(2) Abdollah Jalilian (PhD); Department of Statistics,

Razi University, Kermanshah, Iran

(3) Ramin Rezaei-Zangeneh (MD); Deputy for Treatment,

Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah,

Iran

(4) Teimour Jamshidi (BSc); Head of Research

and Training in Forensic Medicine Organization

of Kermanshah province, Kermanshah, Iran

(5) Epidemiology and Biostatistics Department,

Rafsanjan Medical School, Rafsanjan University

of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran.

(6) Occupational Environmental Research Center,

Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan,

Iran

Corresponding author:

Professor

Mohsen Rezaeian (PhD)

Epidemiology and Biostatistics Department, Occupational

Environmental Research Center

Rafsanjan Medical School, Rafsanjan University

of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan-Iran

Tel: +983434331315

Fax: +983434331315

Email: moeygmr2@yahoo.co.uk

|

Abstract

Background:

Kermanshah

province (the most populated province

in the west of Iran) has one of the highest

suicide rates among Iran's provinces.

This study aims to update the existing

knowledge of suicide situations in the

province in order to take the first step

towards designing preventive interventions.

Methods:

Data were extracted from the electronic

files of the Forensic Medicine Organization

(FMO) of Kermanshah province during the

course of one-year. The chi-squared test

and Cramer's V statistic were used to

assess the associations between the demographic

variables.

Results: 265

confirmed cases (65.7% males and 34.3%

females) of suicide were registered during

the study period. The overall annual rate

of suicide in Kermanshah province was

13.6 persons per 100,000 residents. Approximately,

45% of the cases were between 20 and 29

years old. Hanging in males (50%) and

self-immolation in females (43%) were

the dominant suicide methods.

Conclusion: Compared

to the average suicide rate in Iran, Kermanshah

province has a noticeably higher rate.

Focusing on social determinants of health

in the population should be seriously

considered by the health system's policy-makers

regarding practical approaches to be used

for the purposes of reducing suicide.

Key words:

Measure of association, Social determinants

of health, Suicide, Iran

|

Suicide is one of the most complex aspects

of human behavior where a person ends his/her

life with a deliberate and conscious effort

(1, 2). According to suicide statistics reported

to World Health Organization (WHO), suicide

rates vary greatly among countries (3). There

are several problems and difficulties in accurately

defining, measuring, recording, reporting and

scientific studying of suicide (4). Most of

the problems are related to social stigma associated

with this phenomenon which is prevalent, more

or less, in every community (2). Also, the official

suicide registration system in different communities

varies (3, 5), including in Iran (6, 7). Furthermore,

in some communities, more than one organization

is active in identification and registration

of suicide data and this issue can cause obvious

differences between statistics submitted on

suicide cases (2, 7).

In Iran, suicide has shown an increasing trend

from 1990 to 2010 (8, 9) and distribution of

suicide mortality across the country is more

prevalent among the western provinces (10).

Based on the information obtained from the death

registration system of the Ministry of Health

and Medical Education, the statistics related

to completed suicide in the first nationwide

study of mortality profile in 29 provinces of

the country in 2004 showed that Kermanshah province

accounted for 14.0 per 100,000 and stood at

the 3rd place in the country in terms of high

rates of mortality caused by suicide. It should

be mentioned that the said national average

has been estimated as much as 5.2 per 100,000

in the same year (11). Moreover, Kermanshah

province was second highest in terms of suicide

mortality rate in the country during 2006-2010

(10). Another nationwide study of mortality

profile in 29 provinces of the country in 2010

showed that hanging and self-immolation stood

at 5th place among the leading causes of death

among males and females aged from 15 to 49 years,

respectively (12).

With due observance to the above-mentioned subjects,

analyzing the current situation of suicide among

various age and gender groups of people in Kermanshah

province and evaluating the suicide rates in

these groups are the main objectives of this

study. Based on this issue, not only can the

vulnerable groups be identified, but also a

giant stride can be taken in this province in

order to reduce rates of suicide through updating

knowledge and information required for healthcare

and medical treatment planning and to use the

results to take the first step towards designing

preventive interventions and mental health promotion.

Ethics Statement

Before reviewing data, burial permit number,

name and surname of the deceased were omitted

due to respect to the principle of medical secrecy.

No private information of the deceased who committed

suicide was used in conducted analysis and obtained

results and hence no informed consent was required

for this study. The study protocol was approved

by the research committee of Kermanshah University

of Medical Sciences (No. 93213).

Socio-demographic Characteristics

Kermanshah province is the most populated province

in the west of Iran with 14 counties, 31 cities

and towns and 86 rural districts. Based on the

2011 Census of Population and Housing, Kermanshah

province has 1,945,227 people and accounts for

2.7% share of total population of the country

with approximately 70% of urbanization rate

and nearly 16% of unemployment rate (13).

Data source

In this cross-sectional study; electronic files

of confirmed committed suicide data of the Forensic

Medicine Organization (FMO) of Kermanshah province

collected from March 21, 2012 to March 20, 2013

were used. This electronic file contains the

following variables: death time, permanent residence

of the deceased including urban or rural regions.

Suicide methods included hanging, self-immolation,

firearms, intentional drug-poisoning, self-poisoning

from toxic substances (toxic-poisoning), and

others. The other methods category included

cutting, drowning, jumping from a high place,

and other unspecified means. The age of the

deceased has been calculated according to birth

year. It is worth mentioning that all identified

cases were older than 10 years of age at the

time of the committed suicide; hence, the age

variable was grouped in four categories including

10-19 years, 20-29 years, 30-39 years, and 40

years and above. Marital status consisted of

single, married and unknown. Educational status

was classified into four groups: illiterate,

primary and middle schools, high school and

diploma, and university degrees. Previous history

of attempting suicide includes yes, and no options.

Consistent with previous researchers, occupational

status variable was grouped in six categories

including: housewife, worker and farmer, unemployed

people, school/college student, self-employment

and others (military man, soldier, driver, retired,

other businesses and so on).

To accurately evaluate the incidence rate of

suicide in Kermanshah, the first important step

was to determine some criteria for inclusion

in the study. For example, an autopsy performed

in one of the forensic medical centers in the

province by a forensic pathologist to determine

the cause of death was not a sufficient inclusion

criterion for participating in the study. Therefore,

the cases indicating permanent postal address

of the deceased person living in one of the

cities or villages at the jurisdiction of Kermanshah

province were analyzed in this study. Also,

to quantify the data, the common procedure for

recording the suicide cases was modified in

this study to the effect that when the subjects

of the study were diagnosed with the death caused

by suicide using medical examination and pathological

tests, the number of subjects of the study was

registered in statistical forms of the suicide

data of the same month; i.e., if the result

of pathological tests of a person verifies that

he/she has died due to suicide several months

after the real time of death, the relevant information

is recorded in the statistics related to the

month when the result is specified and not in

the statistics of the real time of death. Thus,

to correct this procedure and prevent misclassification

bias in data analysis, the researcher had to

reset the statistics of suicide cases based

on the real time of death. The above-mentioned

modifications resulted in the improvement of

the quality of the numerator of annual suicide

rates.

Incidence rates were calculated as the number

of suicide cases divided by the corresponding

estimated population, multiplied by 100,000.

The population of Kermanshah province estimation

extracted from provincial statistical yearbook

for 2013 was used as denominators.

Data analysis

We first examined the distribution of completed

suicide within each of the independent variable

categories. The Pearson's chi-square test of

independence at the 0.05 significance level

and the Cramer's V measure of association were

used to assess the associations between each

pair of the demographic variables. The Cramer's

V statistic varies from 0 (no association) to

1 (complete association) and measures the strength

of relationship between nominal variables. According

to this method, qualitative descriptions are

associated with the following intervals: less

than or equal to 0.40, poor agreement; 0.41-0.60,

moderate agreement; 0.61-0.80, good agreement;

0.81-1.00, excellent agreement (14). All statistical

analyses were conducted using Stata software

version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX,

USA).

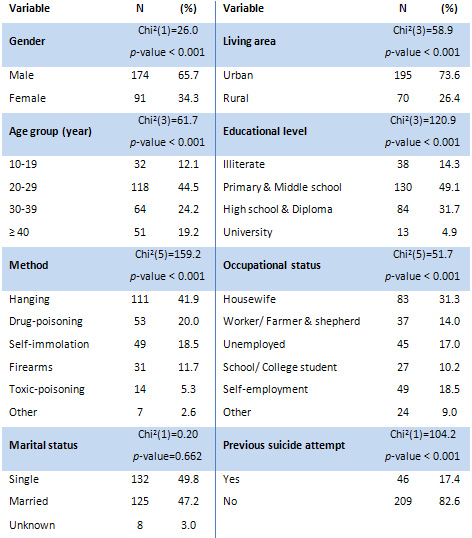

Table

1:

Demographic

characteristics

of

completed

suicide

cases

in

Kermanshah

province,

Iran

(March

2012

to

March

2013)

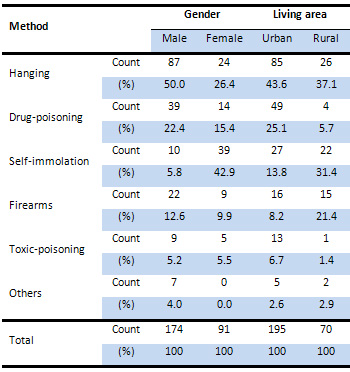

Table

2:

Suicide

methods

among

completed

suicide

cases

by

gender

and

living

area,

Kermanshah

province,

Iran

(March

2012

to

March

2013)

Click

here

for

Table

3:

Chi-squared

statistic

and

p-value

for

the

test

of

independence

between

the

variables

with

their

corresponding

Cramer's

V

measure

of

association

Click

here

for

Table

4:

Absolute

frequency

and

percentage

of

completed

suicide

according

to

days

of

week,

Kermanshah

province,

Iran

(March

2012

to

March

2013)

Click

here

for

Figure

1:

Age-distribution

of

completed

suicide

cases

by

suicide

methods,

Kermanshah

province,

Iran

(March

2012

to

March

2013)

Click

here

for

Figure

2:

Annual

rates

of

completed

suicides

according

to

the

counties,

Kermanshah

province,

Iran,

March

2012

to

March

2013

(ranked

by

suicide

mortality

rate).

A

total

of

265

confirmed

cases

of

death

by

suicide

have

been

registered

from

March

2012

to

March

2013

in

the

population

residing

in

Kermanshah

province,

including

174

men

(65.7%)

and

91

women

(34.3%)

with

a

mean

age

of

31.3±14

years

(Mean±SD).

The

sex

ratio

(male-to-female)

of

the

deceased

stands

at

1.9:1

and

more

than

91%

of

women

were

housewives.

In

addition,

195

persons

(73.6%)

and

70

persons

(26.4%)

of

the

deceased

resided

in

urban

and

rural

regions,

respectively.

There

is

no

significant

difference

(Chi2(1)=0.2,

p-value=0.662)

between

married

and

single

deceased

(excluding

8

cases

with

unknown

marital

status).

More

detailed

information

about

variables

related

to

the

completed

suicide

cases

are

presented

in

Table

1.

For

example,

it

can

be

observed

that

approximately

45%

of

the

deceased

who

committed

suicide

were

in

the

20-29

year

age

group.

Since

the

provincial

statistical

yearbook

had

no

estimates

for

the

population

of

the

province

in

each

age

group

during

the

study

period,

calculation

of

suicide

rate

in

each

age

group

was

impossible.

Nevertheless,

Figure

1

shows

the

absolute

frequency

of

suicide

methods

by

age

groups.

It

can

be

seen

that

intentional

drug-poisoning

is

notably

higher

in

the

20-29

age

group.

The

absolute

frequency

and

percentage

of

suicide

methods

by

gender

and

living

area

are

presented

in

Table

2.

Overall,

the

most

common

suicide

methods

in

Kermanshah

province

were

hanging

(42%)

followed

by

intentional

drug-poisoning

(20%),

and

self-immolation

(18.5%).

The

most

common

suicide

method

was

hanging

(50%)

for

men

and

self-immolation

(43%)

for

women.

Based

on

contents

of

this

table,

68.4%

of

males

have

committed

suicide

using

violent

methods

(hanging,

self-immolation,

firearms)

and

79.1%

of

females

have

committed

suicide

using

the

same

three

violent

methods.

The

overall

annual

suicide

rate

in

Kermanshah

province

is

estimated

at

13.6

per

100,000

residents

during

the

study

period.

Figure

2

shows

the

annual

suicide

rate

of

each

county

of

the

province.

This

figure

shows

that

Qasr-e

Shirin

county

with

27.2

and

Harsin

county

with

7.0

per

100,000

residents

respectively

have

the

highest

and

lowest

annual

suicide

rate

in

the

province.

Thus,

there

is

an

almost

four

times

difference

between

incidences

of

suicide

in

these

counties.

Results

of

Pearson's

chi-square

tests

and

Cramer's

V

values

are

reported

in

Table

3.

According

to

the

results,

suicide

method

is

significantly

associated

with

gender,

living

area,

occupation,

age

group,

education

and

marital

status.

The

corresponding

Cramer's

V

values

indicate

that

the

association

between

suicide

method

and

gender

is

stronger

than

the

association

between

suicide

method

and

any

other

factor.

Similarly,

we

can

see

that

gender

is

significantly

associated

with

occupation,

education,

marital

status

and

living

area.

More

than

17%

of

the

deceased

had

a

history

of

previous

suicide

attempts

but

there

was

no

statistically

significant

association

between

history

of

previous

suicide

attempts

and

other

variables

of

the

study.

Table

4

shows

the

frequency

and

percentage

of

committed

suicide

in

weekdays.

According

to

this

table,

although

Monday

has

a

slightly

higher

frequency

based

on

the

chi-square

test

for

homogeneity,

there

is

no

statistically

significant

difference

(Chi2(6)=12.44,

p-value=0.053)

between

the

frequencies

of

suicide

in

different

weekdays.

As

it

is

observed

from

results

of

this

study,

completed

suicide

has

been

focused

on

in

the

present

study.

The

completed

suicide

statistics

had

appropriate

reliability,

because

the

records

and

reports

of

the

death

due

to

completed

suicide

had

higher

accuracy

in

comparison

to

attempted

suicide

statistics

(15,

16).

Based

on

the

obtained

results,

the

overall

annual

rate

of

completed

suicide

in

this

province

stood

at

13.6

persons

per

100,000

people,

and

suicide

rate

was

observed

more

in

urban

regions

than

rural

regions.

One

of

the

most

important

causes

for

this

event

could

be

increased

level

and

rate

of

urbanization

in

the

province

as

a

result

of

rapid

migration

of

rural

inhabitants

to

urban

areas.

Such

change

in

the

living

environment

has

not

been

adequately

coupled

with

concomitant

cultural

adaptation.

In

this

regard,

the

completed

suicide

rate

in

this

province

is

much

higher

than

that

of

the

national

suicide

rate

(10,

17,

18).

Some

of

the

main

reasons

for

the

high

rate

of

committing

suicide

in

western

provinces

of

Iran

have

been

mentioned

in

previous

research

(2,

7,

10,

17).

The

ratio

of

males

who

died

by

suicide

was

higher

than

that

of

females,

so

this

finding

is

consistent

with

the

results

of

previous

studies

(16).

The

present

study

showed

that

the

majority

of

the

females

who

committed

suicide

were

housewives.

The

reason

for

that

is

most

middle-

and

old-aged

females

in

Iran

are

housewives

without

income.

Therefore,

it

seems

rational

that

the

majority

of

the

females

who

committed

suicide

are

housewives

(16).

The

noticeable

point

is

that

Kermanshah

province

stood

at

the

3rd

place

in

the

country

in

2004

in

terms

of

death

rate

due

to

suicide,

while

four

counties

of

Sarpol-e

Zahab,

Sahneh,

Harsin

and

Qasr-e

Shirin

(all

located

in

Kermanshah

province)

were

among

the

highest

death

rate

caused

by

suicide

across

the

country

(11).

In

the

present

study,

three

counties

of

Qasr-e

Shirin,

Sarpol-e

Zahab

and

Sahneh

are

among

the

highest

suicide

rate

yet

(approximately

20

persons

per

100,000

residents

and

higher).

High

unemployment

rate

in

this

province,

compared

to

the

other

provinces,

has

been

cited

as

one

of

the

main

probable

reasons

for

the

high

rate

of

suicide

in

Kermanshah

province.

Of

course,

relationship

between

economic

problems

and

unemployment

with

suicide

in

Kurdish

ethnicity

has

previously

been

mentioned

(16,

17,

19,

20).

As

mentioned,

hanging

and

self-immolation

are

the

main

methods

of

committing

suicide

among

males

and

females

respectively;

this

finding

is

consistent

with

the

pattern

of

suicide

methods

observed

in

previous

years

in

this

province

(16)

and

also

with

the

governing

pattern

on

the

whole

country

(21,

22)

and

in

Middle

Eastern

countries

(23).

Based

on

this

study,

intentional

drug-poisoning

is

the

2nd

most

common

method

that

leads

to

deaths

due

to

suicide.

This

method

is

frequently

used

in

young

female

attempters

and

also

is

one

of

the

main

methods

of

suicide

in

males

(24).

Frequently

use

of

violent

methods

in

western

provinces

of

the

country

such

as

Kermanshah

province

may

be

due

to

post-war

problems

between

the

Iran

and

Iraq.

This

is

an

important

issue

since,

the

outbreak

of

the

Iran-Iraq

war

in

most

parts

of

western

provinces

of

the

country

including

Kermanshah

province

has

been

cited

as

the

one

of

the

main

reasons

for

occurrence

of

violent

behaviors

including

suicide

(19,

25).

The

reasons

for

the

high

incidence

of

suicide

by

hanging

have

been

studied,

the

results

of

which

indicate

that

hanging

is

a

more

acceptable

method,

and

death

caused

by

hanging

is

less

likely

to

be

misclassified

in

the

death

group

with

ambiguous

reasons

or

accidental

death

due

to

the

transparency

of

death

method

(24,

26).

If

we

study

self-immolation

as

the

main

cause

of

death,

it

can

be

mentioned

that

this

aggressive

and

violent

suicide

method

is

mostly

common

in

developing

countries

such

as

Iran

and

other

Middle

Eastern

countries

(2,

24,

27).

Among

the

main

factors

that

influence

the

acceptability

of

suicide

by

self-immolation,

we

can

refer

to

Kurdish

ethnicity,

female

gender,

young

adult

age

(19),

adjustment

disorder

(19,

28,

29),

cultural

differences

in

attitude

towards

self-immolation,

storage

and

accessibility

of

inflammable

liquids

at

home

and

also

storage

of

kerosene

at

home

for

cooking

usage

(18).

All

of

these

factors

play

an

important

role

in

highlighting

this

violent

suicide

method

in

Kermanshah

province

and

even

"copycat"

phenomenon

can

be

influential

with

regard

to

the

acceptability

of

this

violent

suicide

method

(17).

It

should

be

kept

in

mind

that

like

other

societies

suicide

is

a

phenomenon

that

conflicts

with

religious

and

socio-cultural

values

in

Iran

(2,

15,

20);

so

the

true

suicide

incidence

rate

might

have

been

underestimated

(16).

Undoubtedly,

increasing

mutual

cooperation

and

collaboration

among

official

organizations

involved

in

registration

of

suicide

statistics

is

one

of

the

most

effective

measures

to

promote

quality

of

death

registration

system's

data

in

Iran

(6).

Our

results

furthermore

highlighted

that

most

cases

of

suicide

in

this

province

occur

in

age

group

of

20-29

years.

Also

this

finding

is

consistent

with

the

results

of

previous

studies

(9,

16,

17,

25,

27,

30),

and

the

average

age

of

the

study

subjects

at

the

time

of

death

is

similar

to

the

age

of

the

deceased

from

completed

suicide

in

this

province

(11).

It

should

be

noted

that

the

previous

history

of

attempting

suicide

is

one

of

the

recognized

risk

factors

of

subsequent

suicide

(18,

31).

In

this

study,

more

than

17%

of

the

deceased

caused

by

suicide

had

a

previous

history

of

attempting

suicide,

so

that

activation

of

mental

health

services

after

attempting

suicide

for

the

doer

and

his/her

family

(15,

31)

is

similar

to

launching

an

online

telephone

line

by

psychiatrist

or

hospital

admissions

for

high

risk

cases

(31)

which

can

play

an

important

role

in

prevention

of

re-attempting

suicide

coupled

with

reduced

rate

of

suicide

as

well.

In

western

countries,

most

suicide

cases

occur

on

Mondays

and

Tuesdays

(32,

33).

In

our

study,

there

is

no

significant

difference

among

the

frequencies

of

suicide

in

weekdays.

It

should

be

noticed

that

the

pattern

observed

in

western

countries

may

be

related

to

the

early

days

of

the

business

weeks

but

Monday

in

Iran

is

the

middle

of

the

weekdays.

The

pattern

should

be

taken

into

reconsideration

within

the

longer

time

frame

using

suicide

data

of

other

regions

of

the

country.

Considering

the

above-mentioned

issues,

substantial

efforts

for

preventing

suicides

are

needed

in

western

provinces

of

the

country

(10,

18).

The

policymakers

of

the

health

system

of

the

country

must

seriously

take

into

consideration

the

revision

of

suicide

prevention

programs

and

treatment

of

mental

and

reactive

disorders,

especially

major

depression,

substance

use

disorders,

bipolar

disorders,

mood

and

anxiety

disorders

(9).

We

further

suggest

that

more

information

needs

to

be

gathered

specially

within

suicide

prevention

programs.

These

might

at

the

very

least

include:

"the

causes

for

suicide",

"any

preceding

psychological

disorders

among

suicidal

cases"

and

"the

types

of

any

medical

treatment

they

received".

The

following

are

considered

as

the

main

reasons

influence

on

the

increase

in

suicide

cases

in

the

Middle

Eastern

countries:

Lack

of

success

of

regional

countries

in

accurate

and

suitable

transfer

of

Islamic

values

and

principles

to

the

young

generation;

superficial

attention

to

the

Islamic

rules

and

not

paying

due

attention

to

the

depth

of

these

rules

(such

as

inattention

to

the

fair

distribution

of

wealth

in

society

and

its

role

in

prevention

of

suicide);

inferior

position

of

women

in

some

Middle

Eastern

countries

dating

back

to

the

old

culture

and

tradition

of

the

countries,

such

as

forced

marriage

(23).

It

can

be

understood

easily

that

suicide

is

a

very

complex

and

multidimensional

problem

and

tackling

this

problem

requires

joint

efforts

of

all

people,

society

and

governments.

There

are

several

practical

strategies

to

reduce

the

completed

suicide

rate

and

to

promote

the

mental

health

of

society

across

the

province.

All

of

these

effective

strategies

and

community-based

interventions

should

be

taken

into

consideration

by

policy-makers

of

the

health

system

to

reduce

the

incidence

of

suicide

in

the

west

of

Iran:

-

Paying

enough

attention

to

enhancing

social

equity

and

alleviation

of

economic

problems

and

unemployment

rate;

-

Dissemination

of

culture

of

simple

living

in

society,

especially

among

young

couples;

-

Increasing

the

number

of

family

counseling

centers

and

training

at-risk

individuals

about

coping

skills;

-

Making

effort

in

line

with

promoting

position

of

females

in

society

with

emphasis

on

increasing

participation

of

women

in

the

workforce;

-

Making

effort

in

line

with

adjusting

conflicts

as

a

result

of

incongruousness

and

clash

of

modern

and

traditional

values.

The

authors

would

like

to

thank

Mr.

Shahab

Rezaeian

(PhD

student

of

Epidemiology,

Shiraz

University

of

Medical

Sciences,

Iran)

and

Mrs.

Hadis

Asadi

(MSc

of

Nursing);

as

well

as

the

chairman

and

personnel

of

Imam

Khomeini

hospital

(Eslamabad-e

Gharb,

Kermanshah,

Iran)

for

their

collaboration

throughout

this

work.

1.

Bertolote

JM,

Wasserman

D.

Development

of

definitions

of

suicidal

behaviours.

In:

Wasserman

D,

Wasserman

C,

editors.

Oxford

Textbook

of

Suicidology

and

Suicide

Prevention.

1

ed.

New

York:

Oxford

University

Press;

2009.

p.

87-90.

2.

Rezaeian

M.

Epidemiology

of

Suicide.

In:

Hatami

H,

Razavi

SM,

Eftekhar

AH,

Majlesi

F,

Sayed

Nozadi

M,

Parizadeh

SM,

editors.

Textbook

of

Public

Health.

3rd

ed.

Tehran:

Arjmand

publications;

2013.

p.

1968-93.

3.

Liu

KY.

Suicide

Rates

in

the

World:

1950-2004.

Suicide

Life

Threat

Behav.

2009;39(2):204-13.

4.

Rezaeian

M.

Methodological

issues

and

their

impacts

on

suicide

studies.

Middle

East

J

Business.

2012;7(2):17-9.

5.

Hawton

K,

van

Heeringen

K.

Suicide.

Lancet.

2009;373(9672):1372-81.

6.

Jafari

N,

Kabir

MJ,

Motlagh

ME.

Death

Registration

System

in

I.R.Iran.

Iranian

J

Publ

Health.

2009;38(1):127-9.

7.

Rezaeian

M.

Comparing

the

Statistics

of

Iranian

Ministry

of

Health

with

Data

of

Iranian

Statistical

Center

Regarding

Recorded

Suicidal

Cases

in

Iran.

J

Health

Syst

Res.

2013;8(7):1190-6.

8.

Forouzanfar

MH,

Sepanlou

SG,

Shahraz

S,

Dicker

D,

Naghavi

P,

Pourmalek

F,

et

al.

Evaluating

causes

of

death

and

morbidity

in

Iran,

global

burden

of

diseases,

injuries,

and

risk

factors

study

2010.

Arch

Iran

Med.

2014;17(5):304-20.

9.

Naghavi

M,

Shahraz

S,

Sepanlou

SG,

Dicker

D,

Naghavi

P,

Pourmalek

F,

et

al.

Health

transition

in

Iran

toward

chronic

diseases

based

on

results

of

Global

Burden

of

Disease

2010.

Arch

Iran

Med.

2014;17(5):321-35.

10.

Kiadaliri

AA,

Saadat

S,

Shahnavazi

H,

Haghparast-Bidgoli

H.

Overall,

gender

and

social

inequalities

in

suicide

mortality

in

Iran,

2006-2010:

a

time

trend

province-level

study.

BMJ

Open.

2014;4(8):e005227.

11.

Naghavi

M,

Jafari

N.

Mortality

profile

for

29

provinces

of

Iran

(2004).

Tehran:

Iranian

Ministry

of

Health

and

Medical

Education-Deputy

of

Health;

2007.

12.

Khosravi

A,

Aghamohamadi

S,

Kazemi

E,

Pourmalek

F,

Shariati

M.

Mortality

Profile

in

Iran

(29

Provinces)

over

the

Years

2006

to

2010.

Tehran:

Ministry

of

Health

and

Medical

Education;

2013.

p.

413-4.

13.

Statistical

Center

of

Iran.

Population

and

housing

census

2011

Tehran2011

[2015

Mar

10].

Available

from:

http://www.amar.org.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=1208].

14.

Liebetrau

AM.

Measures

of

association.

Beverly

Hills,

CA:

Sage

Publications

Inc,;

1983.

15.

Najafi

F,

Hasanzadeh

J,

Moradinazar

M,

Faramarzi

H,

Nematollahi

A.

An

epidemiological

survey

on

the

trends

of

the

suicide

incidence

in

the

southwest

Iran,

2004-2009.

Int

J

Health

Policy

Manag.

2013;1(3):219-22.

16.

Poorolajal

J,

Rostami

M,

Mahjub

H,

Esmailnasab

N.

Completed

suicide

and

associated

risk

factors:

a

six-year

population

based

survey.

Arch

Iran

Med.

2015;18(1):39-43.

17.

Ahmadi

AR.

Suicide

by

self-immolation:

comprehensive

overview,

experiences

and

suggestions.

J

Burn

Care

Res.

2007;28(1):30-41.

18.

Ghafarian-Shirazi

HR,

Hosseini

M,

Zoladl

M,

Malekzadeh

M,

Momeninejad

M,

Noorian

K,

et

al.

Suicide

in

the

Islamic

Republic

of

Iran:

an

integrated

analysis

from

1981

to

2007.

East

Mediterr

Health

J.

2012;18(6):607-13.

19.

Ahmadi

A,

Mohammadi

R,

Stavrinos

D,

Almasi

A,

Schwebel

DC.

Self-Immolation

in

Iran.

J

Burn

Care

Res.

2008;29(3):451-60.

20.

Groohi

B,

Rossignol

AM,

Barrero

SP,

Alaghehbandan

R.

Suicidal

behavior

by

burns

among

adolescents

in

Kurdistan,

Iran.

Crisis.

2006;27(1):16-21.

21.

Saberi-Zafarghandi

MB,

Hajebi

A,

Eskandarieh

S,

Ahmadzad-Asl

M.

Epidemiology

of

suicide

and

attempted

suicide

derived

from

the

health

system

database

in

the

Islamic

Republic

of

Iran:

2001-2007.

East

Mediterr

Health

J.

2012;18(8):836-41.

22.

Shojaei

A,

Moradi

S,

Alaeddini

F,

Khodadoost

M,

Barzegar

A,

Khademi

A.

Association

between

suicide

method,

and

gender,

age,

and

education

level

in

Iran

over

2006-2010.

Asia

Pac

Psychiatry.

2014;6(1):18-22.

23.

Rezaeian

M.

Suicide

in

the

middle-eastern

countries:

Introducing

the

new

emerging

pattern

and

a

framework

for

prevention.

Middle

East

J

Business.

2014;9(3):45-6.

24.

Leenaars

AA,

Lester

D.

Domestic

integration

and

suicide

in

the

provinces

of

Canada.

Crisis:

The

Journal

of

Crisis

Intervention

and

Suicide

Prevention.

1999;20(2):59.

25.

Alaghehbandan

R,

Lari

AR,

Joghataei

M-T,

Islami

A,

Motavalian

A.

A

prospective

population-based

study

of

suicidal

behavior

by

burns

in

the

province

of

Ilam,

Iran.

Burns.

2011;37(1):164-9.

26.

Razaeian

M,

Mohammadi

M,

Akbari

M,

Maleki

M.

The

most

common

method

of

suicide

in

Tehran

2000-2004:

implications

for

prevention.

Crisis.

2008;29(3):164-6.

27.

Rezaeian

M.

Suicide

among

young

middle

eastern

muslim

females.

Crisis.

2010;31(1):36-42.

28.

Ahmadi

A,

Mohammadi

R,

Schwebel

DC,

Yeganeh

N,

Hassanzadeh

M,

Bazargan-Hejazi

S.

Psychiatric

disorders

(Axis

I

and

Axis

II)

and

self-immolation:

a

case-control

study

from

Iran.

J

Forensic

Sci.

2010;55(2):447-50.

29.

Ahmadi

A,

Mohammadi

R,

Schwebel

DC,

Yeganeh

N,

Soroush

A,

Bazargan-Hejazi

S.

Familial

risk

factors

for

self-immolation:

a

case-control

study.

J

Womens

Health

(Larchmt).

2009;18(7):1025-31.

30.

Amiri

B,

Pourreza

A,

Rahimi-Foroushani

A,

Hosseini

SM,

Poorolajal

J.

Suicide

and

associated

risk

factors

in

Hamadan

province,

west

of

Iran,

in

2008

and

2009.

J

Res

Health

Sci.

2012;12(2):88-92.

31.

Schwartz-Lifshitz

M,

Zalsman

G,

Giner

L,

Oquendo

MA.

Can

we

really

prevent

suicide?

Curr

Psychiatry

Rep.

2012;14(6):624-33.

32.

Ajdacic-Gross

V,

Tran

US,

Bopp

M,

Sonneck

G,

Niederkrotenthaler

T,

Kapusta

ND,

et

al.

Understanding

weekly

cycles

in

suicide:

an

analysis

of

Austrian

and

Swiss

data

over

40

years.

Epidemiol

Psychiatr

Sci.

2014;23:1-7.

[Epub

ahead

of

print].

33.

Miller

TR,

Furr-Holden

CD,

Lawrence

BA,

Weiss

HB.

Suicide

deaths

and

non-fatal

hospital

admissions

for

deliberate

self-harm:

temporality

by

day

of

week

and

month

of

year,

United

States.

Crisis.

2012;33(3):169-77.

|