|

The

Diagnosis and Management of Dementia

|

|

Authors

David G. Clark, M.D.1

Jeffrey L. Cummings, M.D.2

From the Departments of Neurology (1,2),

and Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences (2),

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, California.

Correspondence

Jeffrey L. Cummings, M.D.

Reed Neurological Research Center

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

710 Westwood Plaza

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1769

Telephone: 310-206-5238

Fax: 310-206-5287

Email: cummings@ucla.edu

The Increasing Burden of Dementing Disease

Dementia is a common, disabling and distressing

neurological disorder and should not be considered a feature

of normal aging. Many people reach old age without developing

disabling cognitive impairment, although some aspects of cognition

routinely change with age. These changes vary among aged individuals

and involve slowing of reaction times and reduction of memory

capacity and visuospatial skills (1). Despite the presence

of measurable neuropsychological alterations in the majority

of elderly people, those who experience these changes typically

retain their ability to conduct their daily social and occupational

activities. These mild alterations stand in stark contrast

to the derangements of cognition that lead to dementia, with

loss of normal function. The proportion of aging individuals

who develop dementia is substantial, and the aging segment

of the population is expanding worldwide.

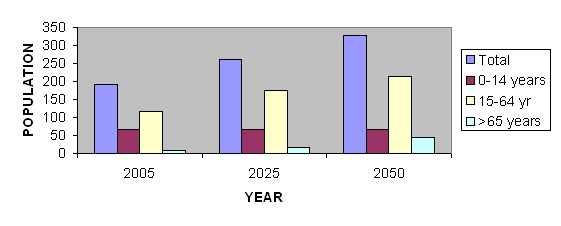

According to World Health Organization (WHO)

estimates, the total population of ten selected Middle Eastern

nations (Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Kuwait, Lebanon,

Libya, Saudi Arabia and Syria) will continue to expand through

the first half of this century, exceeding 326 million by the

year 2050. During this interval the proportion of the population

over the age of 65 will grow at a greater rate than other

segments of the populace. Thus, although only 6.2% of the

adult population of these countries is projected to be over

the age of 65 in 2005, this percentage will rise to 17.1%

by the year 2050 (2) (Figure 1). The expansion of the number

of aged individuals in the population will inevitably be accompanied

by an increasing number of persons with dementia and pre-dementia

mild cognitive impairment (MCI). A further concern is that

this will not be accompanied by a comparable increase in the

occupationally productive segment of the population. While

the 15-64 year old age group is projected to increase by 81%,

the over-65 year-old group will increase by 468%.

Diseases that result in cognitive impairment are common and

increase in prevalence with age. The aged segment of the population

is growing rapidly in most countries of the world and high

rates of dementing disease are expected during the next fifty

years. In the United States there were 2.32 million individuals

with Alzheimer's disease (AD) in 1997 and this number is expected

to increase to at least 8.64 million by the year 2050 (3).

The proportion of new AD cases in Middle Eastern nations may

be similar to that of the US, although few studies are available

to guide predictions. Unless a means is found to prevent or

delay the onset of AD, many of the people in the over-65 age

group will become demented, constituting an overwhelming social

and economic burden as well as a personal tragedy and a challenge

to family

Figure 1 Demography of Aging in Ten Middle Eastern

Nations (population in millions)

Mild Cognitive Impairment

Studies of aging that address the epidemiology

of dementia have revealed the presence of three groups of

individuals: those who are cognitively normal, those who are

demented and a third group that have cognitive impairment

but do not meet criteria for dementia. These individuals may

have impairment in a single domain, usually memory. This third

group of patients cannot be classified as "normal"

or as "demented," since the definition of dementia

requires abnormalities in at least two cognitive domains and

social or occupational disability. These individuals have

been labeled as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The most

clearly characterized form of MCI is known as the "amnestic

form"; these patients are characterized by subjective

memory complaints and evidence objective memory impairment

but have normal cognitive function in other domains and intact

ability to carry out activities of daily living (4)(See Table

1). In research studies, patients typically meet an operational

criterion of 1.5 or more standard deviations below the mean

for age-matched controls on standard neuropsychological tests

of memory (5).

Table 1 Criteria for mild cognitive

impairment (4)

| Memory complaint, preferably corroborated by an informant |

| Objective memory impairment (below 1.5 standard deviations) |

| Normal general cognitive functioning |

| Intact activities of daily living |

| Not demented |

Patients with MCI are at increased risk for

the development of AD. The annual incidence of AD in the general

population ranges from 0.2% among those aged 65-69 years to

3.9% among those aged 85-89, but studies estimate the incidence

rate among patients previously diagnosed with MCI to be between

6 and 25% per year (6). Early recognition of these patients

will become increasingly important as treatments are developed

that delay the transition from MCI to AD. Delaying the onset

of AD by as little as six months will have substantial economic

benefits (3). Several clinical trials are under way to investigate

potential pharmacological treatments for MCI (5). Patients

with other forms of MCI (such as mild changes in more than

one domain or in a single non-memory domain) may be at risk

for other forms of dementia, such as dementia with Lewy bodies,

vascular dementia or frontotemporal dementia (4).

Assessment of Dementia

A number of cognitive instruments have proven

useful for screening patients at risk for dementia. The Mini-Mental

Status Exam (MMSE) is widely used. It is sensitive when scores

are adjusted for age and education (6,7). The validity of

the MMSE in some Arab populations has been investigated and

shown to provide acceptable data (8). Cognitive testing with

a short mental status exam should be supplemented with the

bedside evaluation of memory, language, visuospatial abilities,

and frontal-executive functions. Culturally appropriate versions

of these tasks should be selected. Depression can cause cognitive

changes and patients should be screened with questions about

their mood, tearfulness and suicidal ideation.

In addition to measures of cognitive function,

it is important to identify loss of general function or of

the ability to carry out activities of daily living, such

as bathing, grooming, toileting, eating or more complex activities

expected of aged individuals in their cultural setting. These

facts can be gleaned from the history or by interviewing the

patient's caregiver with structured instruments (9). The clinician

can also gain insight regarding the patient's overall level

of function with global rating scales (9, 10). Such informant-based

scales are useful if the informant is observant.

Every patient with suspected dementia should

undergo a thorough physical and neurologic examination. Medical

illnesses that can result in dementia include thyroid disease,

atherosclerotic vascular disease, collagen-vascular diseases

(such as systemic lupus erythematosus), and infections. Thus,

the clinician must be attentive to the skin for thinning of

hair and eyebrows, spider hemangiomata, palmar erythema, malar

rash or Kaposi's sarcoma. The heart sounds, liver texture

and size, or the presence of fever, hypertension or lymphadenopathy

may also provide important diagnostic clues. Visual field

defects, eye movement abnormalities, facial asymmetry, dysarthria,

focal weakness or spasticity may indicate the presence of

focal brain or brainstem lesions due to stroke, tumor or infectious

diseases such as toxoplasmosis.

Where feasible, patients with a clinical dementia

syndrome should undergo structural brain imaging with noncontrast

computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

to evaluate for focal lesions, deep white matter ischemic

changes and regions of atrophy.

Certain laboratory tests are valuable for the

initial screening of patients with cognitive changes. In particular,

thyroid function tests (thyroid stimulating hormone and free

T4) and the vitamin B12 level should be checked in patients

with cognitive complaints. In cases of borderline B12 deficiency

elevated levels of homocysteine and methylmalonic acid enhance

the sensitivity of the B12 level. Patients with risk factors

for HIV should undergo appropriate tests. The prevalence of

venereal syphilis is low outside of urban areas in most Middle

Eastern countries, reducing the utility of routine syphilis

testing. The occurrence of non-venereal, endemic syphilis

(bejel) in rural regions of North Africa and the Arabian peninsula

increases the need for caution when interpreting serological

tests for syphilis (11). There is little evidence that bejel

ever results in neurologic complications. The 14-3-3 protein

is present in higher levels in the spinal fluid of patients

with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and can be used to support

the diagnosis in patients whose clinical presentation is consistent

with the disorder (12).

Diagnosis of Dementia

Dementia

The definition of dementia provided in the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual, 3rd edition, revised (DSM-IIIR) has been

found to have adequate reliability and should be used for

making the diagnosis (13,14). These criteria were not changed

in the 4th edition, and are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 DSM-IV Criteria for dementia

(13)

| Short- and long-term memory impairment |

| Impairment in abstract thinking, judgment,

other higher cortical function or personality change |

| Cognitive disturbance interferes with significantly

with work, social activities or relationships with others |

| These cognitive changes do not occur exclusively

in the setting of delirium |

Once the presence of dementia is established

an attempt should be made to identify its etiology by use

of the history, clinical exam, neuropsychological assessment,

and, where feasible, imaging and laboratory studies. None

of the currently available biological markers are useful for

establishing with certainty the diagnosis of any of the most

common forms of dementia: Alzheimer's disease (AD), vascular

dementia (VaD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) or frontotemporal

dementia (FTD) (13). Therefore, the clinician must rely on

clinical criteria for making these diagnoses.

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of late-onset

dementia. The National Institute of Neurological and Communicative

Disorders and Stroke- AD and Related Disorders Association

(NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for AD have been shown to have adequate

sensitivity and specificity (see Table 3). Patients nearly

always present with the primary complaint of memory difficulty,

articulated either by the patient or by the family. This is

frequently associated with visuospatial disorientation or

language dysfunction. These may manifest as a tendency to

get lost in familiar locations, reduction in the conceptual

precision of speech or impaired comprehension of complex linguistic

material. Occasionally patients with the neuropathologic changes

of AD present clinically with disruption of a single cognitive

domain other than memory, such as loss of visuospatial or

frontal-executive function or aphasia. Such patients may be

diagnosed with posterior cortical atrophy, frontal variant-AD

or aphasia-predominant AD (15). The diagnosis of AD should

be held in question if there is evidence that the patient's

cognition is being impacted by another psychiatric, systemic

or central nervous system disease. Thus, in patients with

depression, severe hypothyroidism or cerebrovascular disease

the diagnosis of possible rather than probable AD is appropriate

until the cause of the disease is evident.

Table 3 NINCDS-ADRDA Criteria for

the Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease (15)

|

I. Probable AD: Core Diagnostic Features

A. Dementia established by clinical examination

(including MMSE, BRDRS, and neuropsychological testing)

B. Deficit in at least two areas of cognition

i. Memory (required)

ii. Other area besides memory

C. Deficits characterized by gradual onset and

progression, onset after age 40

D. Other systemic disorders or brain disease

do not account for the progressive deficits in memory

and cognition in and of themselves

II. Possible AD: Core Diagnostic Features

A. Dementia syndrome in the absence

of other neurologic, psychiatric, or systemic disorder,

OR

B. Presence of a second systemic or brain disorder

sufficient to produce dementia, which is not considered

to be the primary cause of the dementia

III. Features that make a diagnosis

of Probable or Possible AD unlikely or uncertain

A. Sudden apoplectic onset

B. Focal neurologic findings such as hemiparesis,

sensory loss, visual field deficits, and incoordination

early in the course of the illness

C. Seizures or gait disturbances at the onset

or very early in the course of the illness

IV. Criteria for diagnosis of Definite

Alzheimer's disease:

A. Clinical criteria for probable Alzheimer's disease

B. Histopathologic evidence obtained

from a biopsy or autopsy

As AD progresses, patients frequently

suffer from neuropsychiatric complications such as agitation,

apathy, delusions, hallucinations or depression. In

many cases, these constitute a greater burden for caregivers

than the cognitive deficits and may require treatment

with psychoactive medications.

|

Vascular dementia

Dementia due to cerebrovascular disease should be suspected

when impairment in more than one cognitive domain accompanies

clinical or neuroimaging evidence of stroke. Observed loss

of normal social and occupational functioning required in

the definition of dementia should result from cognitive impairment

and not be explained entirely by the physical disability that

results from stroke. The diagnosis is more certain when there

is a temporal association between clinical stroke and onset

of cognitive impairment, or when family members describe a

stepwise pattern of deterioration. The most common type of

VaD is associated with ischemic injury to subcortical white

matter and lacunar infarctions secondary to small vessel disease.

Patients with VaD often exhibit cortical deficits

associated with focal cerebral lesions, such as aphasia, neglect,

apraxia or dyscalculia. Frontal executive function is commonly

impaired and memory defects follow the frontal-subcortical

pattern, in which patients encode memories adequately but

have difficulty retrieving them.

Four sets of criteria exist for the diagnosis

of VaD. None have been shown to have good specificity, but

all are sensitive. Of these, the Hachinski Ischemic Score

(Table 4) may identify the greatest number of patients with

VaD in spite of not including neuroimaging criteria (13,17).

A score of = 4 is suggestive of AD or other non-vascular causes

of dementia, while a score of = 7 is supportive of a diagnosis

of VaD.

Table 4 Hachinski Ischemic Score (16)

| Abrupt onset |

2 |

| Stepwise deterioration |

1 |

| Fluctuating course |

2 |

| Nocturnal confusion |

1 |

| Preservation of personality |

1 |

| Depression |

1 |

| Somatic complaints |

1 |

| Emotional incontinence |

1 |

| Hypertension |

1 |

| History of stroke |

2 |

| Associated atherosclerosis |

1 |

| Focal neurologic symptoms |

2 |

| Focal neurologic signs |

2 |

Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) has been defined clinically

as a dementia syndrome with parkinsonism, delusions, hallucinations

(especially visual), fluctuating alertness and sensitivity

to neuroleptic medications (See Table 5) (18). The criteria

have poor sensitivity but are very specific (19). The cognitive

profile is remarkable for deficits in attention, visuospatial

reasoning and frontal-subcortical function. When patients

with DLB are compared to patients with AD, memory is significantly

worse in AD, while visuospatial function and executive abilities

are worse in DLB (20). The core clinical features that may

be present include fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations

and parkinsonism. Depression and rapid eye movement (REM)

sleep behavior disorder are also common in DLB.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is characterized by

rigidity, bradykinesia, rest tremor, loss of righting reflexes,

and beneficial response to dopaminergic therapy. Approximately

40% of patients with idiopathic PD meet criteria for dementia

(21). This usually follows a frontal-subcortical pattern,

in which frontal executive functions and memory retrieval

are the most impaired. Patients with PD and dementia typically

have Lewy bodies in the cortex at autopsy. The dementia of

PD may represent a variant of DLB.

Table 5 Criteria for Dementia with

Lewy Bodies (17)

|

I. Progressive cognitive decline interfering

with social and occupational functioning, usually including

deficits of attention, frontal subcortical skills and

visuospatial ability; memory impairment tends to be

a later finding

II. Two of the following core features

are necessary for the diagnosis of probable DLB, one

for the diagnosis of possible DLB:

A. Fluctuating cognition with pronounced variations

in attention and alertness

B. Recurrent visual hallucinations which are

typically well-formed and detailed

C. Spontaneous motor features of parkinsonism

III. Supportive features:

A. Repeated falls

B. Syncope

C. Transient loss of consciousness

D. Neuroleptic sensitivity

E. Systematized delusions

F. Hallucinations in other modalities

IV. A diagnosis of DLB is less likely

in the presence of:

A. Clinical or neuroimaging evidence of stroke

Clinical, laboratory or neuroimaging evidence

for other physical illness or brain disorder that accounts

for the clinical picture

|

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) features early behavioral changes

preceding loss of memory, perception, spatial skills or praxis

(22). This disorder is less common than AD, VaD or DLB. As

is the case with other neurodegenerative diseases, the onset

is insidious and progressive. Those close to the patient frequently

notice a change in personality characterized by tactlessness,

disinhibition, poor impulse control, poor grooming and hygiene,

emotional blunting, mental rigidity and ritualized behaviors

(22). Some patients demonstrate hyperorality, which may manifest

as a craving for sweets, but patients have been described

who chewed compulsively on nonfood objects. Language is often

impacted, and may be characterized by stereotypies and echolalia.

Anomia and reduced verbal output are common. Snout, grasp

and palmomental reflexes may be present (see Table 6.) Onset

of the disorder is typically between the ages of 45 and 65

years.

The clinical syndromes of progressive nonfluent

aphasia and semantic dementia are most often associated with

the neuropathologic changes of FTD. The former is typically

manifested as the insidious onset of anomia that progresses

to nonfluent aphasia, while the latter is characterized by

early loss of word meaning that manifests as failure of single-word

production and comprehension (22). Patients with semantic

dementia often lose conceptual knowledge in other spheres,

resulting in prosopagnosia or visual agnosia (23). Primary

progressive aphasia often leads to complete or nearly complete

mutism.

Table 6 Criteria for Frontotemporal

Lobar Degeneration (21)

|

I. Core diagnostic features

A. Insidious onset and gradual

progression

B. Early decline in social interpersonal conduct

C. Early impairment in regulation of personal

conduct

D. Early emotional bluntingE. Early loss of insight

II. Supportive diagnostic features

A. Decline in personal hygiene

and grooming

1. Mental rigidity and inflexibility

2. Distractibility and impersistence

3. Hyperorality and dietary changes

4. Perseverative and stereotyped behavior

5. Utilization behavior

B. Speech and language

1. Altered speech output

- a. Aspontaneity and economy of speech

- b. Press of speech

2. Stereotypy of speech

3. Echolalia

4. Perseveration

5. Mutism

C. Physical signs

1. Primitive reflexes

2. Incontinence

3. Akinesia, rigidity and tremor

4. Low and labile blood pressure

D. Investigations

1. Neuropsychology: significant impairment of

frontal lobe tests in the absence of severe amnesia,

aphasia, or perceptuospatial disorder

2. Electroencephalography: normal on conventional

EEG despite clinically evident dementia

Brain imaging (structural and/or functional):

predominant frontal and/or anterior temporal abnormality

|

Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease

A great deal of research has focused on identifying

medications capable of slowing or delaying the progression

of AD. A placebo-controlled, double-blind study comparing

selegiline, vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) and a combination

of both drugs demonstrated that all three treatments delayed

the onset of functional dependence and the need for institutionalization

compared to placebo (24). Combination of the two drugs did

not offer significant benefit over either drug alone. Since

vitamin E is inexpensive and relatively safe in patients who

are not on anticoagulation, it is now the standard of care

to administer 1000 IU twice daily to patients diagnosed with

AD. The value of vitamin E in ameliorating other forms of

dementia is not known.

Four medications that block the action of acetylcholinesterase

have been proven to be beneficial for AD. The first of these

to be approved, tacrine, is associated with liver toxicity

and requires QID dosing. Newer agents are less toxic and easier

to use, and tacrine is no longer frequently prescribed (25,26).

Donepezil is a cholinesterase inhibitor that does not require

monitoring of liver function tests and is dosed once per day.

The starting dose of 5 mg is therapeutic; many patients benefit

from titration to 10 mg. Rivastigmine is a cholinesterase

inhibitor that is dosed twice daily, starting with 1.5 mg

tablets. The dose can be increased at 4-week intervals to

3 mg BID, then 4.5 mg BID and finally 6 mg BID if desired

(27). Gastrointestinal side effects (such as nausea or weight

loss) have been reported in 15 to 45% of subjects and result

in discontinuation of the drug in up to 25% (25). Galantamine

is a cholinesterase inhibitor with comparable cognitive benefits

(28). The optimal dose identified is 16 to 24 mg/d, divided

into two daily doses. Galantamine typically is titrated from

4 mg BID, to 8 mg BID, and finally to 12mg BID. Cholinesterase

inhibitors have been shown to improve cognition and global

function compared to placebo. Improved behavior, delayed decline

in function, decreased caregiver burden and deferral of institutionalization

have been suggested by some studies (28,29). Cholinesterase

inhibitors may be useful in other dementias with cholinergic

deficits including the dementia of Parkinson's disease and

DLB (29).

Another approach to treating AD pharmacologically

is to prevent excitotoxicity by blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate

(NMDA) receptors in the brain. This is the rationale for the

use of memantine, which delays the onset of severe functional

disability in patients with AD (30), even in patients who

are already receiving donepezil (32). The medication is started

at 5 mg once per day is titrated weekly in increments of 5

mg, with a target dose of 10 mg BID after four weeks. From

a neuropsychiatric standpoint, the drug seems to reduce agitation

(31-33). Although memantine fares well against placebo in

terms of side effects, it may be associated rarely with confusion

or headaches (32). Table 7 summarizes the medications commonly

used in the treatment of AD.

The benefits of memantine and cholinesterase

inhibitors are modest, and new approaches will be important

for the prevention or postponement of AD. Amyloid accumulation

in the cortex is considered the primary lesion of AD and research

currently is focused on preventing amyloid aggregation. Trials

of a vaccine against amyloid have been disappointing thus

far, due to the development of encephalopathy in some patients

(34), but efforts will continue to focus on vaccination strategies

as well as on beta and gamma secretase inhibitors, copper

and zinc chelators, statins, antioxidants and non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs as means of limiting amyloid or amyloid-related

neuronal injury.

Most patients will develop neuropsychiatric

symptoms during the course of the illness. These symptoms

constitute a weighty burden on caregivers who should be advised

that modification of the patient's environment may reduce

the frequency and severity of these symptoms. Such modifications

may include avoiding overstimulation, following a regular

schedule, and keeping the patient active during the day but

providing quiet relaxing evenings. Cholinesterase inhibitors

and memantine have behavioral as well as cognitive benefits.

Many patients, however, will require psychotropic medications

for neuropsychiatric symptoms. Depression is a feature that

commonly accompanies AD and responds most readily to a non-sedating

serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), such as sertraline

or escitalopram. Tricyclic antidepressants are of limited

usefulness because of sedation and anticholinergic side effects.

Agitation is a common complaint that may be associated with

depression, delusions, hallucinations or insomnia. Depending

on the associated features, clinicians may find use of an

atypical antipsychotic, antidepressant or anticonvulsant to

be useful for reducing agitation. In one trial for agitation

in dementia, risperidone was shown to be as effective as haloperidol,

with fewer extrapyramidal side effects (36). The effective

dose of risperidone is typically 1.0 to 1.5 mg/day. Low-dose

olanzapine (5-10 mg) reduced psychosis and agitation in an

18-week study of patients with possible or probable AD, with

no significant increase in extrapyramidal side effects (37).

Quetiapine represents a feasible alternative to these agents

and may produce fewer extrapyramidal side effects. One preliminary

study of sertraline use for agitation and aggression in severe

AD indicated that some patients responded favorably (38).

Trazodone is an unconventional antidepressant with hypnotic

properties that is useful for insomnia and intermittent agitation

in demented patients (21). In some cases, neuropsychiatric

symptoms may respond to an anticonvulsant with mood stabilizing

properties (39,40).

The late stages of AD and most dementias are

marked by complete functional dependence. Patients are non-ambulatory,

unable to communicate needs and may be unable to feed themselves.

End of life issues must be addressed with patients and family

members before this stage is reached, as many people have

strong feelings regarding use of intravenous hydration or

nasogastric or percutaneous gastrostomy tubes for life support.

As with all bedridden patients, there is high risk for the

development of decubitus ulcers, dehydration, urinary tract

infection, pneumonia and deep venous thrombosis. These risks

may be reduced by adequate physical therapy, frequent turning,

and hydration. Encephalopathy, rather than fever, is often

the earliest sign of infection and should warrant prompt evaluation,

as infections are frequently the cause of death in patients

with dementia.

The Caregiver Alliance

Those caring for demented patients bear a great

physical and emotional burden. Studies of medications for

AD have begun to take this into account; for example, use

of memantine is associated with a reduction in the caregiver

time requirement of about 45.8 hours per month (31). Regardless

of such modest improvements, caregivers remain responsible

for numerous time-consuming tasks, such as supervising patients

in activities of daily living, administering medications,

and restricting driving. In addition, the difficulty of caring

for a patient with dementia has a negative impact on the health

of the caregiver (41). As dementia becomes more prevalent

in society, resources that mitigate the suffering of caregivers

and assist them in coping with the daily management of the

patient will become increasingly necessary.

Table 7 Medications used in the treatment

of AD

Cognitive Agents

|

Starting Dose |

Target Dose |

Uses |

| Donepezil |

5 mg daily

|

10 mg daily |

Improve cognition, may reduce apathy and

hallucinations |

| Galantamine |

4 mg BID

|

12 mg BID |

|

| Rivastigmine |

1.5 mg BID

|

6 mg BID |

|

| Memantine |

5 mg daily

|

10 mg BID |

Slow functional decline, may improve agitation |

| Antidepressants |

|

|

|

| Sertraline |

25 mg daily

|

75-100 mg daily |

Depression and agitation |

Escitalopram

|

5 mg daily

|

10-20 mg daily |

Depression |

| Trazodone |

25 mg QHS

|

100-400 mg daily |

Agitation, insomnia |

| Atypical Antipsychotics |

|

|

|

| Risperidone |

0.25 mg daily |

0.75-1.5 mg daily |

Agitation, delusions, hallucinations |

Conclusion

The prevalence of dementia is rising as the

aged segment of the population grows larger. This growth is

out of proportion to growth in the younger segments of the

population, and dementia will impose an increasing social

and economic burden during the next several decades. Middle-Eastern

nations will experience a marked growth in aged segments of

their populations in the impending decades. The diagnosis

of dementia is best made with clinical assessment including

cognitive testing. Treatments that delay the progression or

improve the symptoms of AD include cholinesterase inhibitors

and vitamin E. The management of neuropsychiatric symptoms

is important for improving quality of life for patients and

caregivers. Researchers and clinicians must recognize cognitive

decline early and identify treatments that will delay or prevent

the onset of dementia. Current trials are focused on identifying

reliable biological markers of dementia, preventing the advancement

of MCI to AD, and finding treatments to slow or halt the progression

of AD and other dementing diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Cummings receives support from an Alzheimer's

Disease Research Center grant (PSOAG16570) from the National

Institute on Aging, and Alzheimer's Disease Research Center

of California grant and the Sidell-Kagan Foundation. Dr. Clark

is supported by the Veteran's Affairs Special Fellowship,

Geriatric Neurology Section.

REFERENCES

| 1. |

Weintraub S. (2000). Neuropsychological

Assessment of Mental State. In Principles of Cognitive

and Behavioral Neurology, M.-Marsel Mesulam, ed. Oxford

University Press, New York, NY. |

| 2. |

Statistics available online

at http://devdata.worldbank.org/hnpstats/ |

| 3. |

Brookmeyer R, Gray S and Kawas

C. (1998). Projections of Alzheimer's disease in the United

States and the public health impact of delaying disease

onset. American Journal of Public Health 88: 1337-1342.

|

| 4. |

Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz

A, Mohs RC, et al. (2001). Current concepts in mild cognitive

impairment. Archives of Neurology 58: 1985-1992. |

| 5. |

Petersen RC. (2003). Mild cognitive

impairment clinical trials. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery

2: 646-653. |

| 6. |

Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli

M et al. (2001). Practice parameter: Early detection of

dementia: Mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based

review). Neurology 56: 1133-1142 |

| 7. |

Kukull WA, Larson, EB, Teri

L et al. (1994). The Mini-Mental Status Exam score and

the clinical diagnosis of dementia. Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology 47: 1061-1067. |

| 8. |

Al Rajeh S, Ogunniyi A, Awada

A, Daif AK, and Zaidan R. (1998). Validation of the Arabic

version of the mini-mental state examination. Annals of

Saudi Medicine 19(2): 150-152. |

| 9. |

Galasko D, Bennet D, Sano

M et al. (1997). An inventory to assess activities of

daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 11: S33-S39. |

| 10. |

Morris JC. (1993). The Clinical

Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules.

Neurology 43: 2412-2414. |

| 11. |

Arya OP. (1996). Endemic treponematoses,

in Manson's Tropical Diseases, G. C. Cook, ed. W. B. Saunders:

London. |

| 12. |

Hsich G, Kenney K, Gibbs CJ,

Lee KH, Harrington MG. (1996). The 14-3-3 brain protein

in cerebrospinal fluid as a marker for transmissible spongiform

encephalopathies. New England Journal of Medicine 335:

924-930. |

| 13. |

Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings

JL et al. (2001). Practice parameter: Diagnosis of dementia

(an evidence-based review). Neurology 56: 1143-1153. |

| 14. |

American Psychiatric Association.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders:

DSM-IV, 4th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric

Association, 1994. |

| 15. |

Galton CJ, Patterson K, Xuereb

JH and Hodges JR. (2000). Atypical and typical presentations

of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical, neuropsychological,

neuroimaging and pathological study of 13 cases. Brain

123: 484-498. |

| 16. |

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein

M et al. (1984). Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease:

report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices

of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force

on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 34: 939-974. |

| 17. |

Moroney JT, Bagiella E, Desmond

DW et al. (1997). Meta-analysis of the Hachinski Ischemic

Score in pathologically verified dementias. Neurology

49: 1096-1105. |

| 18. |

McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka

K et al. (1996). Consensus guidelines for the clinical

and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies

(DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop.

Neurology 47: 1113-1124. |

| 19. |

Holmes C, Cairns N, Lantos P and Mann

A. (1999). Validity of current clinical criteria for

Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia and dementia

with Lewy bodies. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:

45-50.

|

| 20. |

Salmon DP, Galasko D, Hansen

LA et al. (1996). Neuropsychological deficits associated

with diffuse Lewy body disease. Brain and Cognition 31:

148-165. |

| 21. |

Cummings JL and Trimble MR.

(2002). Concise Guide to Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral

Neurology, 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington,

D.C. |

| 22. |

Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson

L et al. (1998). Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A

consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 51:

1546-1554. |

| 23. |

Hodges, JR. (2001). Frontotemporal

dementia (Pick's disease): clinical features and assessment.

Neurology 56(Suppl 4): S6-S10. |

| 24. |

Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG

et al. (1997). A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol,

or both as treatment for Alzheimer's disease. New England

Journal of Medicine 336: 1216-1222. |

| 25. |

Doody RS, Stevens JC, Beck

C et al. (2001). Practice parameter: Management of dementia

(an evidence-based review). Neurology 56: 1154-1166. |

| 26. |

Rogers SL, Farlow, MR, Doody

RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT and the Donepezil Study Group.

(1998). A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial

of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology

50: 136-145. |

| 27. |

Rösler M, Anand R, Cicin-Sain

A et al. (1999). Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in

patients with Alzheimer's disease: international randomised

controlled trial. British Medical Journal 318: 633-640. |

| 28. |

Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Wessel

T, Yuan W and the Galantamine USA-1 Study Group. (2000).

Galantamine in AD. A 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled

trial with a 6-month extension. Neurology 54: 2261-2268. |

| 29. |

Cummings JL. (2000). Cholinesterase

inhibitors: a new class of psychotropic compounds. 157:

4-15. |

| 30. |

Mohs RC, Doody RS, Morris JC

et al. (2001). A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation

of function survival study of donepezil in AD patients.

57: 481-488. |

| 31. |

Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler

A, Schmitt F, et al. (2003). Memantine in moderate-to-severe

Alzheimer's disease. The New England Journal of Medicine

348(14): 1333-1341. |

| 32. |

Tarriot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg

GT, Graham SM, et al. (2004). Memantine treatment in patients

with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving

donepezil. A randomized placebo controlled trial. Journal

of the American Medical Association 291: 317-324. |

| 33. |

Livingston G and Katona C.

(2004). The place of memantine in the treatment of Alzheimer's

disease: a number needed to treat analysis. International

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 19: 919-925. |

| 34. |

Dominguez DI and De Strooper

B. (2002). Novel therapeutic strategies provide the real

test for the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease.

Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 23(7): 324-330. |

| 35. |

Feldman H, Gauthier S, Hecker

J et al. (2001). A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study

of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease.

Neurology 57: 613-620. |

| 36. |

Chan W, Lam LC, Choy CN, Leung

VP, Li S and Chiu HF. (2001). A double-blind randomized

comparison of risperidone and haloperidol in the treatment

of behavioral and psychological symptoms in Chinese dementia

patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry

16: 1156-1162. |

| 37. |

. Street JL, Clark WS, Kadam

DL et al. (2001). Long-term efficacy of olanzepine in

the control of psychotic and behavioral symptoms in nursing

home patients with Alzheimer's dementia. International

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 16: S62-S70. |

| 38. |

Lanctôt KL, Herrman N,

van Reekum R, Eryavec G and Naranjo CA. (2002). Gender,

aggression and serotonergic function are associated with

response to sertraline for behavioral disturbances in

Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Geriatric

Psychiatry 17: 531-541. |

| 39. |

Grossman F. (1998). A review

of anticonvulsants in treating agitated demented elderly

patients. Pharmacotherapy 18(3): 600-606. |

| 40. |

Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello

M and Cazzato G. (2001). Gabapentin as a possible treatment

of behavioral alterations in Alzheimer disease (AD) patients

(letter). European Journal of Neurology 8: 501-502. |

| 41. |

Schultz R and Martire LM. (2004).

Family caregiving of persons with dementia. Prevalence,

health effects, and support strategies. American Journal

of Geriatric Psychiatry 12(3): 240-249. |

|