Iraqi

girl's education: challenges and opportunities

Safaa

Bahjat

Correspondence:

Dr Safaa Bahjat

Allergologist,

Kirkuk

Iraq

Email: docbahjatsafaa2000@googlemail.com

|

To

Whom Is Concerned!

A

coalition to fight ISIS has been launched;

again this is another open war with no

time table, and the battlefield is Iraq,

the world's favoured weapon trials laboratory

on the experimental models Iraqis by the

justificatory rhetoric of war (collateral

damage!).

"What

hypocrisy when some people grow 'indignant'

because one or two of their citizens are

killed".

War has been

described as 'development in reverse'.

Even short episodes of armed conflict

can halt progress or reverse gains built

up over generations, undermining economic

growth and advances in health, nutrition

and employment. The impact is most severe

and protracted in countries and among

people whose resilience and capacity for

recovery are weakened by mass poverty

.Education seldom figures in assessments

of the damage inflicted by conflict. International

attention and media reporting invariably

focus on the most immediate images of

humanitarian suffering, not on the hidden

costs and lasting legacies of violence.

Yet nowhere are those costs and legacies

more evident than in education. Across

many of the world's poorest countries,

armed conflict is destroying not just

school infrastructure, but also the hopes

and ambitions of a whole generation of

children.

Education is seldom a primary cause of

conflict. Intra-state armed conflict is

often associated with grievances and perceived

injustices linked to identity, faith,

ethnicity and region. Education can make

a difference in all these areas, tipping

the balance in favour of peace -or conflict.

When the political leaders do acknowledge

the need to tackle literacy,(allow Iraqis

to extend their knowledge through free

fellowships in the developed countries)

only then they will guarantee winning

the war.

Dr. Safaa

Bahjat

|

The girls in the photo say; 'I want to become

an attorney and be an important person';' I

want to become a teacher'; 'I keep coming to

school because I am a top performer and I want

to finish my education'; ' I like to go to school

and learn';' I want to learn how to read and

write.'

All the available data and available published

information make it clear that Iraq's women, once

a highly educated group, have lost ground in the

last 15 -20 years as girls' participation in education

has declined. A good quality educational system,

which includes and encourages the full participation

of girls, is vital for any country's development.

The full participation of girls is needed not

only because of the value of the contribution

that women are then able to make in social, economic

and political spheres, but because of the well

documented benefit that the educational level

of the wife and mother in a family makes to the

health, well-being and success in life of all

family members. The value of providing good education

for all children is even greater in the case of

Iraq because of the immense development tasks

facing the country. However the available information

suggests that educational disadvantage is increasing

for Iraqi girls as they are disproportionally

less likely to participate and succeed in education

at every age and every level. Half the future

of the country is being wasted. Educational disadvantage

for girls in Iraq has complex causes. It is inextricably

linked with the status of women in Iraqi society

and with the opportunities available to women

in the workplace and in public life, as well as

with social conditions such as poverty, security

and the quality of educational provision.

Although historically Iraqi women and girls had

relatively more rights than many of their counterparts

in the Middle East, major discrepancies have always

existed between rich and poor, urban and rural,

traditional and liberal families with regard to

the education of girls. The Iraqi Provisional

Constitution (drafted in 1970) formally guaranteed

equal rights to women and other laws specifically

ensured their right to vote, attend school, run

for political office, and own property. Since

the 1991 Gulf War, the position of women within

Iraqi society has deteriorated rapidly, with the

predictable impact on girls' education. Women

and girls were disproportionately affected by

the economic consequences of the U.N. sanctions,

and lacked access to food, health care, as well

as education. These effects were compounded by

changes in the law that restricted women's mobility

and access to the formal sector in an effort to

ensure jobs to men and appease conservative religious

and tribal groups.

After seizing power in 1968, the secular Ba'ath

party embarked on a programme to consolidate its

authority and to achieve rapid economic growth

despite labour shortages. Women's participation

was integral to the attainment of both of these

goals, and the government passed laws specifically

aimed at improving the status of women. The status

of Iraqi women was directly linked to the government's

over-arching political and economic policies.

Until the 1990s, Iraqi women played an active

role in the political and economic development

of Iraq. A robust civil society had existed prior

to the coup d'état in 1968, including a

number of women's organizations. The Ba'ath Party

dismantled most of these civil society groups

after its seizure of power. Shortly thereafter

it established the General Federation of Iraqi

Women. The General Federation of Iraqi Women played

a significant role in implementing state policy,

primarily through its role in running more than

250 rural and urban community centers offering

job-training, educational, and other social programmes

for women and acting as a channel for communication

of state propaganda. Female officers within the

General Federation of Iraqi Women also played

a role in the implementation of legal reforms

advancing women's status under the law and in

lobbying for changes to the personal status code.

The primary legal underpinning of women's equality

was set out in the Iraqi Provisional Constitution,

which was drafted by the Ba'ath party in 1970.

Article 19 declares all citizens equal before

the law regardless of sex, blood, language, social

origin, or religion. In January 1971, Iraq also

ratified the International Covenants on Civil

and Political Rights and Economic, Social and

Cultural Rights which provide equal protection

under international law to all.

In order to further its programme of economic

development, the government passed a compulsory

education law mandating that both sexes attend

school at the primary level. The Compulsory Education

Law 118/1976 stated that education is compulsory

and free of charge for children of both sexes

from six to ten years of age. Girls were free

to leave school thereafter with the approval of

their parents or guardians. Although middle and

upper class Iraqi women had been attending university

since the 1920s, rural women and girls were largely

uneducated until this time. In December 1979,

the government passed further legislation requiring

the eradication of illiteracy. All illiterate

persons between ages fifteen and forty-five were

required to attend classes at local "literacy

centers," many of which were run by the General

Federation of Iraqi Women(GFIW). Although many

conservative sectors of Iraqi society refused

to allow women in their communities to go to such

centers (despite potential prosecution), the literacy

gap between males and females narrowed. The Iraqi

government also passed labour and employment laws

to ensure that women were granted equal opportunities

in the civil service sector, maternity benefits,

and freedom from harassment in the workplace.

Such laws had a direct impact on the number of

women in the workforce. The fact that the government

was hiring women contributed to the breakdown

of the traditional reluctance to allow women to

work outside the home. The Iraqi Bureau of Statistics

reported that in 1976, women constituted approximately

38.5 percent of those in the education profession,

31 percent of the medical profession, 25 percent

of lab technicians, 15 percent of accountants

and 15 percent of civil servants.

During the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88), women assumed

greater roles in the workforce in general and

the civil service in particular, reflecting the

shortage of working age men. Until the 1990s,

the number of women working outside the home continued

to grow.

Legislative reforms in this period reflected the

Ba'ath Party's attempt to modernize Iraqi society

and supplant loyalty to extended families and

tribal society with loyalty to the government

and ruling party. In the years following the 1991

Gulf War, many of the positive steps that had

been taken to advance women's and girls' status

in Iraqi society were reversed because of a combination

of legal, economic, and political factors. The

most significant political factor was Saddam Hussein's

decision to embrace Islamic and tribal traditions

as a political tool in order to consolidate power.

In addition, the U.N. sanctions imposed after

the war have had a disproportionate impact on

women and children, especially girls. The gender

gap in school enrolment (and subsequently female

illiteracy) increased dramatically due to families'

financial inability to send their children to

school. When faced with limited resources, many

families chose to keep their girl children at

home. According to the United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO),

as a result of the national literacy campaign,

as of 1987 approximately 75 percent of Iraqi women

were literate; however, by year-end 2000, Iraq

had the lowest regional adult literacy levels,

with the percentage of literate women at less

than 25 percent.

Women and girls have also suffered from increasing

restrictions on their freedom of mobility and

protections under the law, which again predictably

impact on the access of girls to education. In

collusion with conservative religious groups and

tribal leaders, the government issued numerous

decrees and introduced legislation which had a

negative impact on women's legal status in the

labour code, criminal justice system, and personal

status laws. In 2001, the U.N. Special Rapporteur

for Violence against Women reported that since

the passage of the reforms in 1991, an estimated

4,000 women and girls had been victims of so called

"honour killings."

Additionally, as the economy constricted, in an

effort to ensure employment for men the government

pushed women out of the labour force and into

more traditional roles in the home, so that the

education of girls became less significant as

they were unlikely to work outside the home. In

1998, the government reportedly dismissed all

women working as secretaries in governmental agencies.

In June 2000, it also reportedly enacted a law

requiring all state ministries to put restrictions

on women working outside the home. Women's freedom

to travel abroad was also legally restricted and

formerly co-educational high schools were required

by law to provide single-sex education only, further

reflecting the reversion to religious and tribal

traditions. As a result of these combined forces,

by the last years of Saddam Hussein's government

the majority of women and girls had been relegated

to traditional roles within the home and the education

of girls had, predictably declined still further.

By 2000, budget constraints were also seriously

limiting the provision of textbooks and other

teaching and learning materials. Less money was

available to rehabilitate dilapidated school so

children were increasingly unable to study in

properly functioning school buildings. The war

begun in 2003 further contributed to the decline

in the quality of education with the greatest

impact on the education of girls with an increase

in both real and perceived levels of danger outside

the home, declining quality teaching and an increase

of religious conservatism in some parts of the

country.

Currently, despite some positive achievements

in northern and southern Iraq, ongoing violence

is posing new challenges in the country's central

zone. In an insecure atmosphere where schools

have been targeted, many parents have to choose

between education and safety for their children,

with girls once again the most affected.

When wars break out, international attention and

media reporting invariably focus on the most immediate

images of human suffering. Yet behind these images

is a hidden crisis. Across many of the world's

poorest countries, armed conflict is destroying

not just school infrastructure, but the hopes

and ambitions of generations of children. Half

of them are girls. The hidden crisis in education

in conflict-affected states is a global challenge

that demands an international response. As well

as undermining prospects for boosting economic

growth, reducing poverty and achieving the Millennium

Development Goals, armed conflict is reinforcing

the inequalities, desperation and grievances that

trap countries in cycles of violence.

Displaced populations are among the least visible

Mass displacement is often a strategic goal for

armed groups seeking to separate populations or

undermine the livelihoods of specific groups.

At least 500 000 people in Mosul have been displaced,

according to the International Organization for

Migration (IOM). 100 000 of these people are being

hosted in Kirkuk, Erbil, Duhauk and Sulaimanya,

while 200 000 people who were not able to pass

through border checkpoints remain located in disputed

areas adjacent to the Kurdish border. A further

200 000 people have been displaced from the west

to the east side of Mosul. An additional 470 000

people were displaced earlier by fighting between

the Iraqi army and armed opposition groups who

have controlled the cities of Ramadi and Fallujah

since January. The new flood of displaced people

from Mosul almost doubled Iraq's internally displaced

persons caseload in less than 1 week and "created

an alarming environment in Iraq", though

the real number is almost certainly higher. Recent

estimates suggest that almost half of refugees

and internally displaced people (IDPs) are under

18. Many do not have the documents.

Gender parity in education is a fundamental

human right, a foundation for equal opportunity

and a source of economic growth, employment

and innovation. Gender disparities originate

at different points in the education system.

Tackling gender disparities in secondary school

poses many challenges. Some of the barriers

to gender parity at the primary level are even

higher at the secondary level. Secondary schooling

is far more costly, often forcing households

to ration resources among children. Where girls'

education is less valued, or perceived as generating

lower returns, parents may favour sons over

daughters. Early marriage can act as another

barrier to secondary school progression. Parents

may also worry more about the security of adolescent

girls because secondary schools are often further

from home than primary schools. The case for

gender fairness in education is based on human

rights, not economic calculus. Schooling can

equip girls with the capabilities they need

to expand their choices, influence decisions

in their households and participate in wider

social and economic processes. By the same token,

there is clear evidence that economic returns

to female education are very high - and, at

the secondary level, higher than for boys. The

implication is that countries tolerating high

levels of gender inequality in education are

sacrificing gains in economic growth, productivity

and poverty reduction, as well as the basic

rights of half the population. When girls enter

school they bring the disadvantages associated

with wider gender inequality, which are often

transmitted through households, communities

and established social practices. Education

systems can weaken the transmission lines, but

building schools and classrooms and supplying

teachers is not enough. Getting girls into school

and equipping them with the skills they need

to flourish often require policies designed

to counteract the deeper causes of gender disadvantage.

Public policy can make a difference in three

key areas: creating incentives for school entry,

facilitating the development of a 'girl-friendly'

learning environment and ensuring that schools

provide relevant skills. In most cases, simultaneous

interventions are required on all three fronts.

In Iraq young girls are less likely to enter

the school system and more likely to drop out

of primary school, and few make it through secondary

school. Interlocking gender inequalities associated

with poverty, labour demand, cultural practices

and attitudes to girls' education create barriers

to entry and progression through school and

reduce expectations and ambition among many

girls.

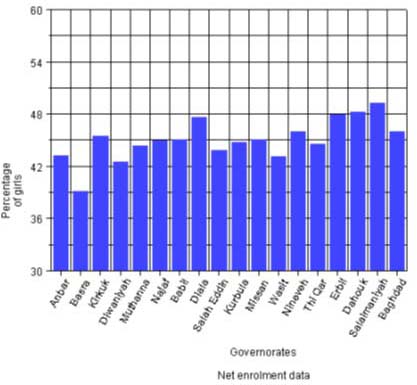

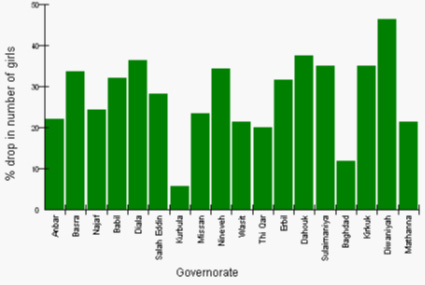

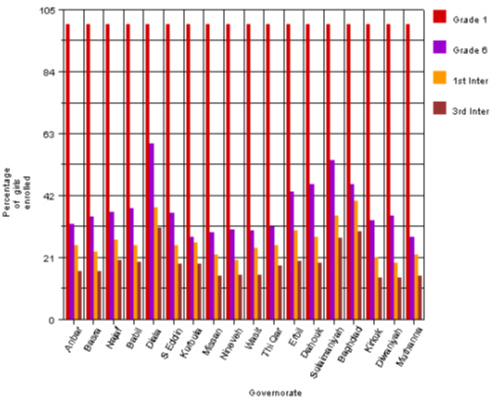

In Iraq the overall number of children receiving

primary education has declined between 2004-05

and 2007-08 by 88,164, with no improvement in

the percentage of girls enrolled. Gross enrolment

figures provided for the academic year 2005

- 2005 show 5,163,440 children enrolled in primary

education. Girls account for 44.74% of students.

Figures for 2007-2008 show 5,065,276 children

enrolled in primary education, with 44.8 % being

girls. This means that for every 100 boys enrolled

in primary schools in Iraq, there are just under

89 girls. This under representation of girls

in primary school in Iraq has been known for

many years. The fact that there are declining

numbers of girls in each successive grade has

also been identified by analyses of the data.

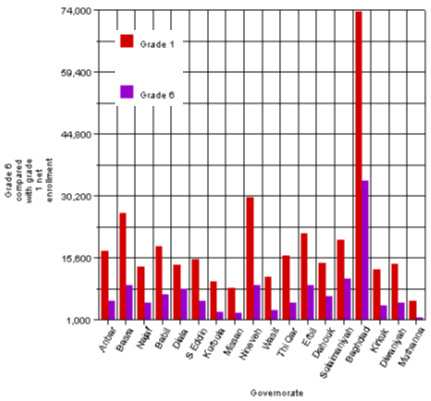

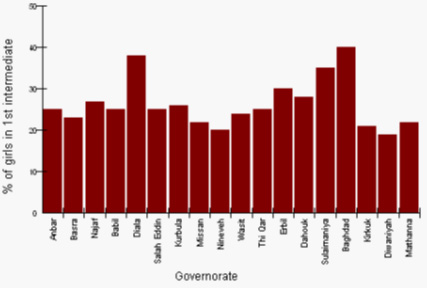

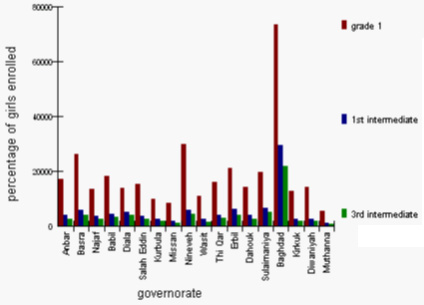

Analysis of the 2007 -2008 data shows the same

picture. In every governorate a smaller percentage

of girls than boys start school. There are no

governorates where the number of children completing

primary education is acceptable, and it is even

less acceptable for girls. The current data

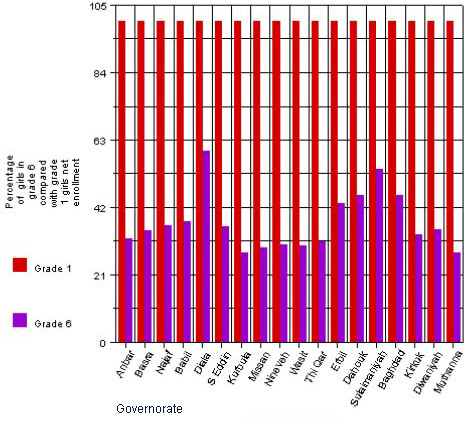

replicates previously available data in showing

a generally declining percentage of girls in

each successive primary school grade. Some 75%

of girls who start school have dropped out during,

or at the end of, primary school and so do not

go on to intermediate education. Many of them

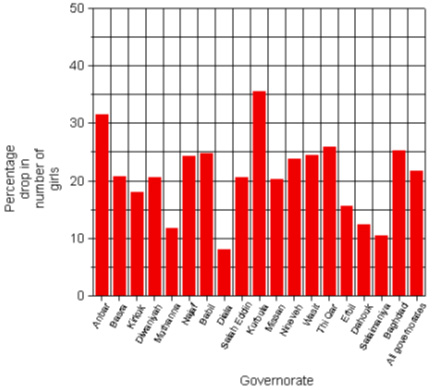

will have dropped out after grade 1. When all

governorates' figures are combined, there are

21.66% fewer girls in grade 2 than in grade

1. Similarly there is a 28.63% national drop

in the number of girls between grades 5 and

6. By the first intermediate class, only 25%

the number of girls in grade 1 are in school;

by the third intermediate class the figure is

20%.The percentage of girls in primary school

classes is highest in Erbil, Dohuk and Sulaimaniya.

These three governorates also have the highest

percentage of children in pre-school education.

In Erbil 15.8% of children attend preschool

provision, Dohuk 11.3% and Sulaimaniya 11.4%

compared with, for example 5.7% in Baghdad,

8.6% in Kirkuk, or 3.3% in Diyala. There is

also a major issue with the number of children

in each grade who are over age. The difference

between gross and net enrolment data for 2007-08

shows that 659,896 children are above the age

for the grade that they are in. This represents

13% of all primary school children - more than

one in every ten. Of those children, 228,829

children were still attending primary school

when they were aged 13 - 15+.The net enrolment

rate for girls is 45.8%, as against a gross

enrolment rate of 44.8%. This shows a significantly

greater number of overage boys than girls. For

example, only one third of teenagers still in

primary schools were girls.

In order to increase girls' participation in

education, it is vital to gain an insight into

why they never attend school or drop out before

completing their basic education. A small scale

survey of 80 Iraqi girls was therefore included

in the piece of work. While this is not a large

or statistically valid sample, their responses

provide a clear insight into many of the reasons

why girls do not go to school. As would be expected,

parents, particularly fathers, play a major

role in whether the girls can attend school

or not. The girls refer to a range of reasons

why families do not support girls attending

school. These include concerns about safety,

family poverty, a reluctance to allow adolescent

girls to continue to attend school, the distance

from home to school, early marriage and the

need to help at home. The journey to and from

school presents problems caused by fast traffic,

dogs or boys. Girls are frequently demotivated

by the behaviour of teachers who beat them,

distress them and are unwilling to explain subject

matter that a student does not understand. Their

answers make frequent references to being beaten

or insulted by teachers, and to teachers being

unwilling to give explanations in lessons or

support students in their learning. The girls

describe their schools as unwelcoming and unpleasant

with too few facilities and resources. Schools

are described as dirty, poorly maintained and

uncomfortable, with dirty lavatories and no

drinking water available. Safety is an issue,

particularly in areas of major instability and

insecurity. The concerns about safety relate

to both military conflict and civil crime such

as abduction and rape.

To address the issues identified, sets of recommendations

are included in the report for the government

and education services in Iraq, to address key

policy issues and their implementation; Those

for the government focus on policy development

and implementation are, awareness-raising, school

improvement and development, pre-service and

in-service teacher training, curriculum development,

alternative education strategies, and security

for girls travelling to and from school.

The education system is facing a number of major

difficulties. The system is chronically underfunded

and is currently unable to respond to the demands

despite efforts being made to improve the situation

Even where conditions are improving, a significant

number of older children and young adults have

missed out on crucial phases of their education

and there are few opportunities for them to

make good the years they have lost. The factors

that contribute to placing Iraqi girls at an

educational disadvantage and which need to be

addressed through educational policy and its

implementation include:

_ Lack of a school place;

_ Shortage of teachers, particularly experienced

teachers;

_ The unacceptable behaviour of some teachers

and principals;

_ Dirty and dilapidated school buildings which

lack basic facilities;

_ Attitudes to girls' education;

_ Lack of security;

_ Lack of transport when distances are considerable

or the journey is hazardous;

_ Poverty; no money for clothing and school

supplies and other indirect costs of going to

school;

_ Disability;

_ Being needed in the home;

_ Being needed to make a contribution to the

family's business or income;

_ Lack of official papers

Issues related to school infrastructure

If girls are to attend school, there must be

a school for them to attend and teachers to

teach them. Currently, there is an insufficient

number of schools in good repair, with basic

facilities for all girls to receive their entitlement

to schooling and it is often difficult for girls

to travel to and from school and there are particular

issues when intermediate schools are situated

outside the communities in which girls live.

The third most frequent response to the question

as to why girls between 6 and 17 who are not

in school are not attending was that no school

was available nearby. The number and location

of schools, and their capacity, must therefore

become a key educational issue for each governorate.

There are places where schools are not available

locally and some schools are very overcrowded

and some have too few pupils. If universal basic

education is to be achieved, there must be a

school place for every child. This cannot be

achieved easily or quickly, but an analysis

of the number of school places needed, and where

they are needed, could lead to an effective

and realistic action plan to provide them. An

adequate number of school places would encourage

more girls to enrol in school and decrease the

need for the shift system, which many girls

in the survey indicated that they disliked.

The rehabilitation of dirty and dilapidated

school buildings which lack basic facilities

must also be a policy priority if girls are

to be encouraged to participate in education.

In many cases the quality of the physical environment

does not encourage girls to go to school. Many

schools are in poor repair, are being used for

other purposes or have been destroyed. The lack

of acceptable sanitation and hygiene facilities

is particularly unacceptable to girls and to

their parents. Even if a school place in a clean,

modern building were available for every girl

in Iraq, this would count for nothing unless

well trained teachers, upholding the expected

standards of their profession were available

to teach them. There is currently a shortage

of teachers, particularly experienced teachers.

The number of teachers available, particularly

well qualified and experienced teachers is an

issue and currently it is doubtful that there

are sufficient skilled and experience teachers

in Iraq to make it possible for all girls to

go to school and receive good quality teaching.

"The number of teachers leaving the country

this year (2006) is huge and almost double those

who left in 2005," Professor Salah Aliwi,

director-general of studies planning in the

Ministry of Higher Education told reporters

during an Aug. 24, 2006 interview in Baghdad.

"Every day, we are losing more experienced

people, which is causing a serious problem in

the education system."This has caused a

decline in the quality of teaching as experienced

teachers left the country or ceased teaching

because of attacks and lack of security. As

security is improving teachers may return to

Iraq, or return to teaching, but it is unlikely

that they will all do so. To address this issue,

in-service training needs to be provided to

existing teachers to upgrade their skills and

the number of well trained new teachers entering

the profession needs to be increased. High quality

training programmes and packages need to be

developed to achieve this. The biggest drop

in the number of girls enrolled in primary school

in Iraq takes place between grade 1 and grade

2. Measures need to be taken to address this.

The practice of using subject teachers rather

than one class teacher for all subjects in the

early grades makes schooling unfriendly for

younger children and consideration should be

given to phasing this out by training primary

school teachers to deliver the whole curriculum

to their classes, with only a very few exceptions

for specialist subjects. The unacceptable behaviour

of some teachers and principals in terms of

physical and psychological punishments must

be stopped, through training, effective management

and through the creation and implementation

of an effective disciplinary system to deal

with those who behave unacceptably. Buildings

and teachers, however high quality both may

be, are of no value if girls are prevented from

attending school by families, or societal attitudes

or by cultural norms and expectations which

do not encourage the education of all children.

There is considerable anecdotal evidence and

some research evidence, such as Yasmin Husein

Al-Jawaheri's empirical research, published

in Women in Iraq: The Gender Impact of International

Sanctions, that attitudes towards girls and

women have become, and are still becoming, more

repressive and against the participation of

girls in education and women in public life.

Conservative beliefs are believed to be leading

to violations of the rights of girls and women

to life, physical integrity, education, health

and freedom of movement. A lack of optimism

about the future means that families see little

point in making the investment in the future

that education represents, particularly for

girls who are seen to be unlikely to have careers

-'Combined with the high rates of anxiety, depression,

and post-traumatic stress disorders suffered

by a large part of the war-affected population,

these factors could have serious consequences

on the physical and psychological health of

Iraqi women, requiring interventions to help

families and communities cope.' A major challenge

to the development of an effective education

system for girls in 21st century Iraq is the

need to challenge and change attitudes to girls,

their education and their future lives as women

in society. Families and fathers in particular,

need to be persuaded that their daughters must

attend school. Religious and community leaders

are key figures in promoting education for all

children and for girls in particular and consideration

should be given to involving them at all levels

in campaigns to bring about universal basic

education in Iraq and restoring the country

to its previous position as a leader in region.

Informal and non formal educational provision

should be developed for girls who are not allowed

to go to school and for older girls and young

women who have missed the opportunity to benefit

from basic education and are now too old to

return to school.

Issues related to security and the journey

to and from school

However much they may value education and however

good it may be, parents are always unwilling

to expose their children and particularly their

daughters, to danger. The lack of security in

some parts of Iraq makes parents reluctant to

allow their daughters to go to schools and makes

girls reluctant to attend. There is no doubt

that the government of Iraq is making every

possible effort to bring security to the country,

but there are major issues in many areas which

cannot be resolved quickly or easily. There

are also issues concerning the lack of transport

when distances are considerable or the journey

is hazardous. The Ministry of Education should

therefore consider home and distance learning

options for girls for whom attendance at school

is too difficult, dangerous or impossible in

current circumstances. Home and distance learning

options could also be useful for girls who cannot

travel outside their home area to intermediate

school, for example, or for girls whose families

will not allow them to attend school.

Issues related to poverty

Although education is free in Iraq, school attendance

is not without costs, both direct and indirect.

Some families have insufficient money for clothing

and school supplies and others need their daughter's

contribution to the family's business or income

either by the girl working or by her providing

domestic help so that others may work. In the

northern Kurdish territory, mounting poverty

is said to contribute to the use of child labour

and prevents children from attending school.

Although Iraqi officials believed that the 2007-2008

school year would see a much larger number of

new school enrolments, 76.2%of respondents to

A Women for Women survey of 1,513 Iraqi women

said that girls in their families are not allowed

to attend school, and 56.7% of respondents said

that girls' ability to attend school has become

worse over the last four years. According to

Women for Women International Iraq staff, the

primary reasons for this are poverty and insecurity.

While 49.6% of respondents describe their opportunities

for education as poor, and 16.6% say they have

no opportunities at all, 65.1% of respondents

say it is extremely important to the welfare

and development of their communities that women

and girls in Iraq be able to access educational

opportunities.

Issues related to disability

Every difficulty faced by Iraqi girls of school

age in attending school will be at least doubled

for girls with a disability. If the distance

to school, the poor state of the buildings,

the absence of basic facilities, unsympathetic

teachers, and lack of help in understanding

lessons, family protectiveness and the attitudes

of society are barriers to many girls attending

school, they are likely to be insurmountable

blocks for girls with disabilities. Careful

consideration needs to be given to preventing

disability wherever possible and to providing

different access routes to education, including

distance and home learning opportunities, for

girls who cannot attend schools with their non-disabled

peers.

Lack of official papers

Many children come from internally displaced

families and do not have the documents required

to register for school and this needs to be

addressed through the appropriate channels as

quickly as possible so that children do not

continue to miss out on education. Children

who stop going to school become less and less

likely to return as time goes by and so it is

essential that any gaps in school attendance

are remedied as soon as possible and that children

who have had a period out of school are helped

back into regular attendance through bridging

programmes.

Children who lack the skills for school

Although girls have more limited access to education

than boys, are less likely to complete their

primary education and are much less likely to

complete their secondary education, there is

also an increase in the number of boys not attending

school or succeeding in their education.

Participation would be improved by the provision

of pre-school education, linked to feeding programmes

in very poor areas, to increase children's language

development and prevent the consequences of

poor nutrition. Evidence is increasing that

it is likely that a large number of children

in Iraq suffer from preventable learning difficulties

related to lack of early stimulation and learning.

The Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey carried

out in 2006 found that 18% of two year old Iraqi

children could not name at least one object.

In Salahuddin as many as 35% of two year olds

were not able to do this. Two year olds with

normal language development could be expected

to have a vocabulary of some 150 -300 words.

This degree of language delay may result from

widespread psycho-social consequences of war,

including increased poverty and fearfulness.

In times of peace and optimism adults naturally

talk to babies and young children without being

taught about the benefits of early stimulation.

However, psychosocial difficulties and poverty,

including, preoccupation with day-to- day survival,

amongst adults prevent them from being able

to talk to or stimulate their children in the

normal way. The children therefore do not develop

adequate language skills. Children with such

very limited language are very unlikely to be

ready to succeed in education when they reach

school age. They will be unable to understand

or respond to the school curriculum and are

at risk of dropping out of school. The same

survey reports that 15% of Iraqi children between

2 and 14 years of age have at least one type

of disability - a large number being impairment

or of speech and language. An emphasis on the

development of early language skills could therefore

increase the number of children entering school

with enough language to participate in learning

and decrease the number of children who drop

out of school in the early grades because they

do not have sufficient language skills to benefit

from the education provided. Such initiatives

would benefit all young children, but girls

would benefit most. Language delay and difficulties

make school enrolment less likely as families

will often keep children at home if they know

that they will not be able to cope at school.

For those who do enrol, difficulties in such

a crucial area for learning create major barriers

to achievement in school. Failure then causes

children to drop out of education. In addition

to the difficulties caused by lack of stimulation,

children's cognitive development is also affected

by poor nutrition. Brain development is most

sensitive to a baby's nutrition between mid-pregnancy

and two years of age. Children who are malnourished

throughout this period do not adequately grow,

either physically or mentally. Their brains

are smaller than normal and they also lack a

substance called Myelin. Myelin is a very dense,

fatty substance that insulates the electrical

pathways of the brain, rather like the plastic

coating on a power cable. It increases the speed

of electrical transmission and prevents adjacent

nerve fibres from mixing their messages. Myelination

(the coating or covering of axons with myelin)

begins around birth and is most rapid in the

first two years. Because of the rapid pace of

myelination in early life, children need a high

level of fat in their diets -some 50 percent

of their total calories- until about two years

of age. Inadequate brain growth and inadequate

myelination are reasons why children who were

malnourished as foetuses and infants suffer

lasting behavioural and cognitive deficits,

including slower language and fine motor development,

lower intelligence (IQ), and poorer school performance.

So decreasing stunting and wasting as a result

of poor nutrition will also increase the chances

of children attending school and achieving.

Figures suggest that in addition to the worryingly

large numbers of children who never enroll in

school, over 100,000 children who enroll in

grade 1 each year do not enter grade 2 and another

100,000 drop out between grades 2 and 3. Many

of these children will fail in these early grades

because they have learning difficulties caused

by lack of brain development in their early

years as a result of under stimulation or poor

nutrition which has impaired their ability to

learn.

Recommendations to the government of Iraq

to improve the current situation

As the 2007 Annual Report for UNICEF Iraq rightly

notes ' Substantial impact on children's wellbeing

will only emerge once major gaps in Iraq's weak

legislative and social work systems for children

are bridged - an effort likely to take some

years.' The people who will be part of bridging

those major gaps are the children of today.

Half of them are girls. Unless efforts are made

today to improve the education of children,

especially girls who fare even worse than boys

in the current situation, the nation's capacity

to build a strong and effective legislative

framework and a much needed, fully functioning

social work system, will be severely compromised.

To improve the education system, it is recommended

that the new Government of Iraq that will be

in power following the 2010 elections:

• Makes education a key priority by publicly

and wholeheartedly subscribing to a vision for

compulsory primary education in which all children

are able to attend school, learn well and achieve

their potential. This should be based on the

concept that, other than in rare health related

cases, there are no valid reasons for a child

of primary school age to be out of school. All

policies, strategic plans and action plans must

include a specific section on the education

of girls and strong reassertion, at national

level of the right of every girl to attend school

and the benefits of education to the girls,

their families and to the country in general

• develop an updated national policy framework

based on the inclusion of every child of primary

school age in school;

• implement the content of the policy through

a clear 10 year national strategic plan for

improving education for all Iraqi children,

with a substantial separate section on the issues

which have a particular impact on girls' education.

The strategic plan would include, for example,

the identification of areas of greatest deprivation

and need; the building and refurbishment of

schools so that they all have decent lavatories

and access to drinking water, the phasing down

of the shift system, national awareness and

attitude changing campaigns; strategies to enable

even the poorest children to attend school;

improving the training, in-service support and

improved management of teachers. The section

on issues which relate to the issues which have

a particular impact on girls' education would

include, for example, an increased number

of intermediate schools for girls, strategies

for keeping girls safe, the development of teaching

materials and teaching methodologies which include

girls and their learning styles

• establish an annual action plan, linked

to the national plan, in every governorate in

Iraq, which is monitored and its implementation

evaluated each year

• develop a major national initiative for

the in-service retraining and management of

teachers so that they develop skills for effective

teaching to enable the range of children in

their classes to learn effectively and do not

physically or mentally abuse students and so

that they can be taught effectively

• plan and implements a national campaign,

supported by influential religious and civil

leaders and linked to improved security, to

encourage families to see it as their religious

duty and duty

as citizens to send their daughters to school.

• increase pre-school education for 3-5

year olds to ensure that they are developing

the skills and concepts that they need to learn

successfully in school.

• develop home and distance learning programmes,

and informal and non-formal educational approaches

for girls who cannot attend school for any reason,

including lack of security, parental attitudes,

and disability.

• develop programmes for older girls and

young women who have not completed their basic

education and are now too old to return to school.

Figure 1: Percentage of girls in primary

education by governate

Figure 2: Girls decline in numbers. Grade

6 compared to Grade 1

Figure 3: Girls decline in numbers. Grade 6

compared to Grade 1

Figure 4: Percentage drop in the number

of girls between Grades 1 and 2

Figure 5: Percentage drop of number of girls

between Grade 6 and 1st intermediate

Figure 6: Percentage of girls in 1st Intermediate

class as compared with Grade 1

Figure 7: Decline in numbers in net enrolment

of girls - Grade 1 to 3rd intermediate

Figure 8: Girls decline in numbers - Grade

1 to 3rd intermediate class

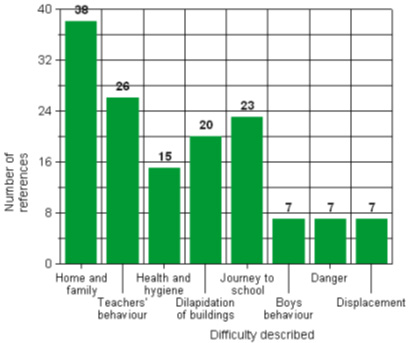

Figure 9: Difficulties in school access

References

and

bibliography

for

this

report

Access

t1o

Education

in

Iraq:

A

Gender

Perspective,

OCHA

Iraq/UNAMI

(Information

Analysis

Unit

2008

Al-

Jawaheri,

Yasmin

Husein.

Women

in

Iraq:

The

Gender

Impact

of

International

Sanctions

2008

The

Arab

Human

Development

Report

2005.

United

Nations

Development

Programme

Arab

Fund

for

Economic

and

Social

Development,

Arab

Gulf

Programme

for

United

Nations

Development

Organizations

Baghdad

Burning:

Girl

Blog

from

Iraq,

by

Riverband,

published

by

Marion

Boyars

2005

Comprehensive

Food

Security

and

Vulnerability

Analysis

in

Iraq.

United

Nations

World

Food

Programme,

2008

Country

Reports

on

Human

Rights

Practices.

Released

by

the

Bureau

of

Democracy,

Human

Rights,

and

Labour

February

28,

2006

De-Baathification

of

Iraqi

Society,"

May

16,

2003

[online].

Educational

statistics

in

Iraq

2003-2004.

Republic

of

Iraq,

Ministry

of

Education

in

collaboration

with

UNICEF

Educational

statistics

in

Iraq

2007-2008.

Republic

of

Iraq,

Ministry

of

Education

in

collaboration

with

UNICEF

Foran,

Siobhán;

Access

to

Education

in

Iraq:

A

Gender

Perspective,

OCHA

Iraq/UNAMI

(InformationAnalysis

Unit

2008)

Haddad,

Subhy.

'New

school

year

begins

in

Iraq

amid

parents'

fresh

worries'

www.chinaview.cn

2009-09-28

Harris

Dale

B.

Goodenough-Harris

Drawing

Test.

Children's

Drawings

as

Measures

of

Intellectual

Maturity

(1963).

Iraq

Multiple

Indicator

Cluster

Survey

2000

Iraq

Multiple

Indicator

Cluster

Survey

2006

Multiple

Indicator

Cluster

Survey

2006:

volume

1

Final

report

Official

Website

of

the

Multi-National

Task

Force.

Http://Www.Mnf-Iraq.Com/Index.Php

Rassam,

Amal.

Political

ideology

and

women

in

Iraq:

Legislation

and.

Cultural

constraints,

Journal

of

Developing

Societies,

vol.

8,

1992

Rekindling

Hope

In

A

Time

of

Crisis.

A

Situational

Analysis.

UNICEF

2007

Revolutionary

Command

Council

Law

No.

139,

December

9,

1972

Coalitional

Provisional

Authority

Order

No.

1

Suad,

Joseph,

"Elite

Strategies

for

State-Building:

Women,

Family,

Religion

and

State

in

Iraq

and

Lebanon,"

in1

Women,

Islam

and

the

State,

ed.

Deniz

Kandiyoti

(Leiden,

The

Netherlands:

E.J.

Brill,1992),

p.

178-79

Survey

of

children

who

drop

out

of

school.

Ministry

of

Education

and

UNICEF;

Sri

Lanka

2009

UNDP/Ministry

of

Planning

and

Development

Coordination:

Iraq

Living

Conditions

Survey.

UNFPA:

United

Nations

Population

Fund

website

|