|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor) |

|

|

|

|

........................................................

|

Original

Contribution/Clinical Investigation

|

|

|

<-- Turkey -->

Very high

levels of C-reactive protein should alert the

clinician to the development of acute chest

syndrome in sickle cell patients

[pdf version]

Can Acipayam, Sadik Kaya, Mehmet Rami Helvaci,

Gül Ilhan, Gönül Oktay

<-- Jordan -->

Seroprevalence

of HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis infections among

blood donors at Blood Bank of King Hussein Medical

Center: A 3 Year Study

[pdf

version]

Baheieh Al Abaddi, Maha Al Amr, Lamees Abasi,

Abeer Saleem, Nisreen Abu hazeem, Ahmd Marafi

|

|

........................................................ |

Medicine and Society

........................................................

International Health

Affairs

.......................................................

Education

and Training

.......................................................

Continuing

Medical Education

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| August 2014 -

Volume 12 Issue 6 |

|

Prevalence

of Helicobacter Pylori Infection in Adult Patients

with Dyspepsia in Gastrointestinal and Hepatology

Teaching Hospital, Baghdad 2012

Hadeer

Salah Al-Deen Abd Elwahhab (1)

Sanaa Jafar Hamodi Alkaisi (2)

Rayadh A. Zaydan (3)

(1) M. B. Ch. B postgraduate resident Doctor

in the Arab Board of Family medicine, Baghdad

.Iraq.

(2) M.B.Ch.B,F.I.B.M.S.\F.M Senior Specialist

Family Physician, Supervisor in the Residency

Program of Arab Board of Family Medicine, Member

in the Executive Committee of Iraqi Family Physicians

Society (IFPS), Co-manager of Bab Almudhum Specialized

Family Medicine Health Center, Baghdad, Iraq.

(3) C.A.B.M., F.I.C.M.S. (CE).Consultant

of Gastroenterology , Supervisor in the Residency

Program of Arab Board for Health Specializations

,in Subspecialty of Gastroenterology, Gastroenterology(GIT)

Center, Baghdad -Iraq.

Correspondence:

Dr.Sanaa Jafar Hamodi Alkaisi,

Co-manager of Bab Almudhum Specialized Family

Medicine Health Center,

Baghdad, Iraq.

Email:

drsanaaalkaisi@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Background:

Dyspepsia is a common symptom with an

extensive differential diagnosis and a

heterogeneous pathophysiology. Helicobacter

pylori infection may be an etiological

factor in some patients. The infection

is chronic and common throughout the world,

with a higher prevalence in developing

than in developed countries.

Objectives: To demonstrate the

prevalence of Helicobacter Pylori infection

in adult patients with dyspepsia who underwent

upper Oesophagio-Gastro-Duodenoscopy so

early treatment can be made to prevent

it`s complications, and to estimate the

prevalence of positive endoscopic findings

in patients with dyspepsia.

Patients and methods: This is a

descriptive cross sectional study carried

out in the gastro-intestinal and hepatology

teaching hospital, Baghdad Medical City

during 2013 on data collected from reviewing

patient's files from the 1st of January

to 31st of December 2012 including all

adults 18 years and above of both sexes

with dyspeptic symptoms who were referred

for endoscopic evaluation of Helicobacter

Pylori infection by taking multiple

antral biopsies for histopathological

stain and evaluation of their endoscopic

findings.

Key words: helicobacter pylori,

adult patients, dyspepsia, Baghdad

|

Dyspepsia is a common symptom with an extensive

differential diagnosis and a heterogeneous pathophysiology.

It occurs in approximately 25 percent (range 13

to 40 percent) of the population each year, but

most affected people do not seek medical care.

[1]

Dyspepsia is often broadly defined as pain or

discomfort centered in the upper abdomen and may

include multiple and varying symptoms such as

epigastric pain, postprandial fullness, early

satiation (also called early satiety), anorexia,

belching, nausea and vomiting, upper abdominal

bloating, and even heartburn and regurgitation.

Patients with dyspepsia commonly report several

of these symptoms.[2]

The pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia is

poorly understood. However, researches have focused

on abnormal gastric motor function, increased

visceral sensitivity, psychosocial factors and

recently, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

infection of the stomach. [3]

H. pylori infection is chronic and common

throughout the world, with a higher prevalence

in developing than in developed countries [4].

It has been reported that 20% to 60% of patients

with functional dyspepsia have evidence of

H. pylori gastritis and that eradication

of the organism results in symptomatic benefit

in a small number (10%) of these patients. Therefore,

patients younger than 55 years who have new-onset

dyspepsia without alarm features should undergo

H. pylori testing and treatment if infection

is confirmed. [5]

H. pylori infection can be diagnosed

by non-invasive methods or by endoscopic biopsy

of the gastric mucosa. The non-invasive methods

include the urea breath test, serologic tests

and stool antigen assays. Histology of endoscopically

taken biopsy has a very high sensitivity and

specificity of 96% and 98.8% respectively, even

though it requires expertise for interpretation.

[6]

Although there are several reports on the correlation

between H. pylori infection and clinical

outcomes, the results remain unclear and show

discrepancies. [7] This study therefore determined

to investigate H. pylori infection and its relation

with dyspepsia.

1. To estimate the prevalence of H.

Pylori infection in adult patients with dyspepsia

who underwent upper Oesophagio-Gastro-Duodenoscopy

(OGD) by histopathological stain so early treatment

can be made to prevent it`s complications.

2. To estimate the prevalence of positive

endoscopic findings in patients with dyspepsia.

Study Design: This is a descriptive cross

sectional study carried out in the GIT and hepatology

teaching hospital, Baghdad-Medical City during

2013 on data collected from reviewing patient's

files from the 1st of January to 31st of December

2012.

Inclusion criteria: Any patient more than

18 years old of both sexes who presented to the

GIT hospital during the year 2012 with any of

the dyspeptic symptoms and was diagnosed as having

dyspepsia according to Rome III and admitted for

endoscopic evaluation of H. Pylori infection

by taking multiple gastric biopsies for histopathological

stain and evaluation of their endoscopic findings

was included.

Exclusion criteria: None of the patients

selected were on antibiotic treatment for the

last 4 weeks before endoscopy, and none was on

NSAID's or PPI or steroids therapy, and none of

them had hematemesis or melena at presentation.

Data collection: Data was collected from

patients file information in regard to patient's

name, age, gender, residency and presenting symptoms

(postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric

pain, epigastric burning, bloating, nausea, vomiting

and belching), endoscopic findings and histopathological

stain results for H. Pylori. Data was collected

during a three months period from the 1st of January

to 31st of March 2013, on a basis of one day per

week.

Endoscopy: Upper gastroendoscopy by

video-endoscope was performed on each patient

for the evaluation of gastro-duodenal changes

and biopsy collection. Patients were fasted

overnight. The esophagus, stomach and duodenum

were all visualized and mucosal findings on

endoscopy were noticed. Three antral biopsies

were obtained for histology.

Histology: Biopsies were placed in 10%

formalin and then processed for histological

examination. Sections were stained with Hematoxylin

and Eosin stain (H & E stain) and examined

by an experienced histopathologist.

Limitations of the study:

The main limitations found for this study were:

1. This is a cross sectional study so

temporal relationship between cause-effect cannot

be determined.

2. Shortage of information available

on the patients in the hospital records.

Statistical analysis: Data of all patients

were checked for any errors or inconsistency

then transferred into computerized statistical

software; Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS) version 17 was used in all statistical

analysis and procedures. The student t test

was used to find the significance of differences

in mean age in patients with and without H.

Pylori infection. Chi square (X2)

was used to find the significance of differences

in the distribution of H. Pylori infection

among patients according to different variables

in the study and to assess the significance

of the relation between H. Pylori infection

and these variables. Fisher's exact test was

used alternatively when the chi square was inapplicable.

The level of significance was set at P-value

< 0.05

to be considered as a statistically significant

difference.

H. Pylori infection was detected in

164 (82%) patients versus 36 (18%) patients

who were free of H. Pylori infection.

The relation of H. Pylori infection with

age from different aspects of view: There was

a statistically significant relation between

age and the prevalence of H. Pylori infection,

(P-value =0.001); the infection was more prevalent

among patients with age (28 - 37) years followed

by those aged <

27 years. None of those aged >

78 years had positive H. Pylori infection,

(Table 1).

Table 1: Relation between H. Pylori infection

and age of the patient

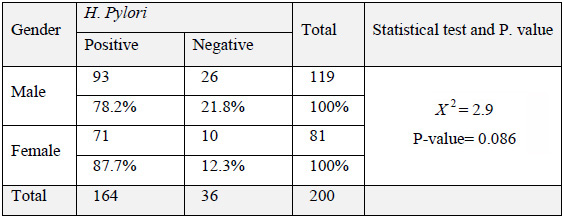

H. Pylori infection was present in 93

(78.2%) of 119 males and 71 (87.7%) of 81 females

with no statistically significant difference

between both genders in the prevalence of H.

Pylori infection, P-value >0.05, (Table 2).

Table 2: Relation between H. Pylori infection

and gender

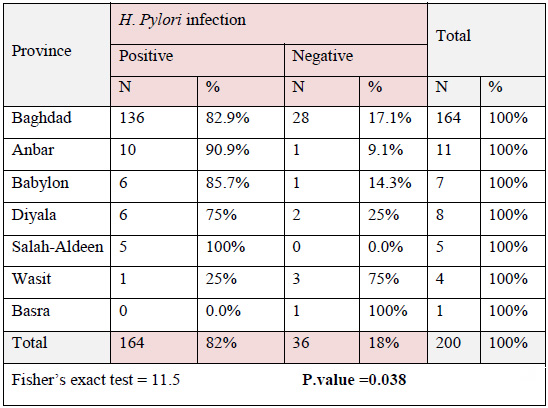

H. Pylori infection was more prevalent

among patients from Salah-Aldeen province (100%),

while there was none among patients of Basra

province (0.0%), P-value = 0.038, (Table 3).

Table 3: Relation between H. Pylori infection

and provinces of residency

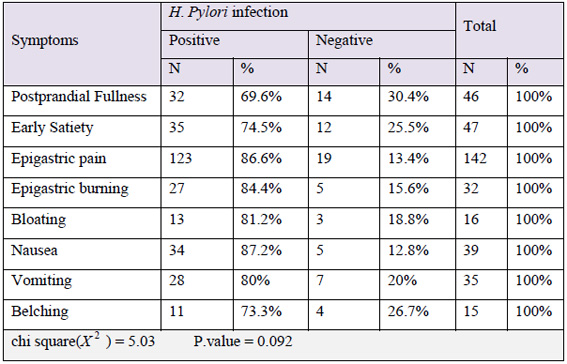

Summarization of the distribution of symptoms

according to the presence of H. pylori

infection and multiple complaints were recorded

in the same patient. There was no statistically

significant relation between symptoms and H.

Pylori infection, P-value >0.05, (Table

4).

Table 4: Relation between H. Pylori infection

and symptoms

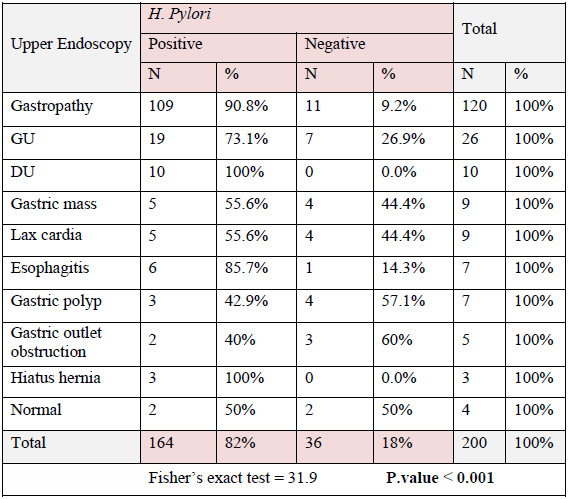

The infection rates in patients with D.U. and

hiatus hernia were significantly higher than

the rates among patients with other endoscopic

finding or with normal endoscopic findings;

P. value was highly significant (<0.001)

( Table 5).

Table 5: Relation between H. Pylori infection

and endoscopic findings

This study shows the relation between dyspeptic

symptoms, endoscopic findings and various patient`s

parameters with H. Pylori infection among

the study sample.

Overall H. Pylori infection presents in

82% of the study sample where 18% were free of

the infection. This agrees with studies done in

Iraq (Mosul[8], Anbar[9], Basra[10]), Saudia Arabia

[11], North Jordan [12], Iran [13] , Kuwait [14],

and Libya [15].

Whereas a lower rate of infection was detected

in Jammu/ India[16], Jammica / Italy[3], Thailand[7].

The higher rate of detection of H. pylori in this

study and other developing countries of the Eastern

Mediterranean Region than in developed countries

may be attributed to the genetic predisposition

of the ethnic groups (mainly Arabs) or to local

environmental issues, including dietary factors,

inadequate living conditions, poor sanitation,

hygiene and overcrowding.

Prevalence rates of H. pylori infection

had shown a strong relation with young age group,

residency of middle provinces of Iraq, positive

endoscopic findings, but not with gender or presenting

symptoms. It had been significantly found that

the prevalence of H. Pylori infection decreased

with advancing age (P-value = 0.001) as it is

acquired at younger age. This is in accordance

to the results on Saudi patients [11], Iran [13],

Libya [15], Jammu/ India [16]. While in North

Jordan [12] the prevalence of H. Pylori

increases significantly with age (100% infection

rate in patients over 80 years of age). This was

more proven when comparing the mean age for patients

with positive and negative H. Pylori infection.

Where the mean age for patients with positive

H. Pylori infection was younger than that

of those free of it (40.16 ± 15.5 vs.51.1

± 18.7) years respectively and this difference

was statistically significant, P-value =0.002.

This may indicates that the infection with H.

Pylori occurs at earlier age. Factors such

as severe atrophy or intestinal metaplasia mean

that the local environment is no longer ideal

for the growth of H. pylori. This may contribute

to the lower prevalence in elderly patients.[13]

Males were more infected than females, and the

prevalence of H. Pylori infection among

males was less than that among females involved

in the study (78.2% vs 87.7%) with no statistical

significant relation (P- value = 0.086). The same

results were found in Anbar/ Iraq [9], Saudia

Arabia [11], Jammu/ India [16].

While in North Jordan [12], Kuwait [14] females

were more infected than males with lower infection

rate among females than males but also with no

statistical significant relation.

H. Pylori was strongly related to provinces

of residency (P- value =0.038), and it was most

prevalent among patients from provinces in the

middle of Iraq,while the least infection rate

was found in patients from provinces in the South.

This difference may be because of the small sample

size or may be related to different living standards

including overcrowding and atmosphere temperature.

Epigastric pain was the most frequent symptom

seen in 75% of patients with positive H. pylori

infection while belching being the least frequent

one. This result agrees with the results of Iran

[13], Jammu/ India[16] and Jamica/ Italy [3].

This may be explained in that epigastric pain

especially if associated with dyspeptic symptoms

is more associated with abnormal gastric pathology.[11]

On the other hand H. Pylori infection was

most prevalent in patients suffering from nausea

and least prevalent in patients with postprandial

fullness; but the prevalence of H. Pylori

infection has no statistical significant relation

with the presenting symptom in this study. It

is now accepted that H. pylori is not associated

with a specific symptom profile. This was like

North Jordan [12]. While in Saudi Arabia[11] and

Iran [13] H. Pylori infection was more common

among patients suffering from epigastric pain.

The most common +ve endoscopic finding in this

study was gastropathy in 120 patient (60%) and

the least was Hiatal Hernia (3 patients). There

was a significant relation between H. Pylori

infection and endoscopic findings (p-value <

0.001). It was seen in all patients with D.U.

and hiatal hernia (100% for each). While in Mosul/

Iraq [8], North Jordan[12] and Libya[15] infection

rate was 100% among patients with G.U. The possible

explanation for the lower infection rate among

patients of this study with G.U. than the other

studies is that it may be due to errors in the

sampling technique. One half of the patients of

this study with normal endoscopic findings have

+ve H. Pylori. This goes with results from

Libya [15], Thailand [7] and differs from Jamaica/

Italy [3], and this may indicate that H. Pylori

may be a cause of functional dyspepsia.

The H. pylori infection is frequent in

patients with dyspepsia which decreases with increasing

age with higher infection rates in patients from

provinces of the middle of Iraq. Positive endoscopic

findings were significantly related to H. pylori

infection and pathological dyspepsia has higher

infection rate than NUD. Although half of the

patients with NUD were reported to harbor H.

pylori infection, yet this study cannot prove

a causality relationship between H. Pylori

infection and dyspepsia because the descriptive

study cannot prove it.

1. There is a need to increase awareness

of the role of H. Pylori in causation

of dyspepsia.

2. There is a need for early detection

of H. pylori infection and its eradication to

prevent medication abuse of acid suppression

and an improvement in overall quality and severity

of dyspeptic symptoms.

3. There is a need for more rapid and

non-invasive methods for screening of H.

Pylori infection in patients with un-investigated

dyspepsia to be available at the primary care

centers (as a cost effective methods) to reduce

the overcrowding on specialty hospitals and

minimizes cost and consequences of delayed treatment

because dyspepsia is common and strongly correlated

to H. Pylori infection.

4. It is recommended that endoscopy be

used for patients with dyspepsia that is undiagnosed

by other methods and unresponsive to treatment

to identify those who are infected by H.

pylori and treated accordingly.

5. It is recommended to do analytic study

to prove the cause and effect relationship which

include therapeutic interventional studies to

prove the improvement of symptoms after treatment.

1- Longstreth GF, Talley

NJ, Grover S. Functional

dyspepsia. UpToDate[CD-Room].

2011; 19(3).

2-Tac J. Dyspepsia. In:

Feldman M, Friedman LS,

Brandt LJ, editors. Sleisenger

and Fordtran's gastrointestinal

and liver disease: pathophysiology,

diagnosis, management.

9th ed. Saunders: Elsevier;

2010. P. 183-193.

3-Lee MG, Emery H, Whittle

D, Jackson D, Donaldson

EK: Helicobacter pylori

infection in patients

with functional dyspepsia

in Jamaica. The Internet

Journal of Tropical Medicine.

2009[cited 2012 Oct 19];

5(2): [about 3 p.]. Available

from: http://www.ispub.com/journal/the-internet-journal-of-tropical-medicine/volume-5-number-2/

4-Siddiqui ST, Naz E,

Danish F, Mirza T, Aziz

S, Ali A. Frequency of

Helicobacter pylori in

biopsy proven gastritis

and its association with

lymphoid follicle formation.

J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;

61(2): 138-141.

5-Herrine SK, Fekete T,

Bosworth BP, Kozuch P,

Loren DE, Navarro VJ,

et al. Gastroenterology

and hepatology. In: Alguire

PC, editors. MKSAP15 [CD

Room]. USA: American College

of physicians; 2009.

6-Mustapha SK, Bolori

MT, Ajayi NA, Nggada HA,

Pindiga UH, Gashau W,

et al. Endoscopic findings

and the frequency of Helicobacter

Pylori among dyspeptic

patients in north-eastern

Nigeria. The Internet

Journal of Gastroenterology.

2007 [cited 2012 Oct 19];

6(1): [about 4 p.]. Available

from: http://www.ispub.com/journal/the-internet-journal-of-gastroenterology/volume-6-number-1/

7-Chomvarin C, Kulsuntiwong

P, Mairiang P, Sangchan

A, Kulabkhow C, Chau-in

S, et al. Detection of

H. Pylori in dyspeptic

patients and correlation

with clinical outcomes.

Southeast Asian J Trop

Med Public Health. 2005;

36(4): 917-922.

8- Ayoub MA. Frequency

of Helicobacter Pylori

infection among dyspeptic

patients in Mosul. A dissertation

submitted to Iraqi Board

for Medical Specializations

in Medicine. 2009.

9- Baqir HI, Abdullah

AM, Al-Bana AS, Al-Aubaidi

HM. Sero-prevalence of

Helicobacter Pylori infection

in unselected adult population

in Iraq. IJGE. 2002; 1(3):

22-29.

10- Al-Sulami A, Al-Kiat

HS, Bakker LK, Hunoon

H. Primary isolation and

detection of Helicobacter

Pylori from dyspeptic

patients: a simple, rapid

method. Eastern Mediterranean

Health Journal. 2008;

14(2): 168-176.

11- Abo-Shai MA, El-Shazly

TA, Al-Johani MS. Clinical,

endoscopic, pathological

and serological findings

of Helicobacter Pylori

infection in Saudi patients

with upper gastrointestinal

diseases. British Journal

of Medicine and Medical

Research. 2013; 3(4):

1109-1124.

12- Bani-Hani KE, Hammouri

SM. Prevalence of Helicobacter

Pylori in north Jordan.

Endoscopy based study.

Saudi Med J. 2001 Oct

[cited 2014 April 14];

22 (10): 843-7. Available

from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Prevalence+of+Helicobacter+pylori+in+Northern+Jordan.+Endoscopy+based+study.

13- Shokrzadeh L, Baghaei

K, Yamaoka Y, Shiota S,

Mirsattari D, Porhoseingholi

A, et al. Prevalence of

Helicobacter Pylori in

dyspeptic patients in

Iran. Gasroenterology

Insights. 2012; 4(8):

24-27.

14- Abahussain EA, Hasan

FAM, Nicholls PJ. Dyspepsia

and Helicobacter Pylori

infection: analysis of

200 Kuwaiti patients referred

for endoscopy. Annals

of Saudi Medicine. 1998;

18(6): 502-505.

15- Bakka AS, El-Gariani

AB, AbouGhrara FM, Salih

BA. Frequency of Helicobacter

Pylori infection in dyspeptic

patients in Libya. Saudi

Med J. 2002; 23(10): 1261-1265.

16- Kumar R, Bano G, Sharma

S, Gupta Y. Clinical profile

in H. Pylori positive

patients in Jammu. JK

Science. 2006; 8(3): 148-150.

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|