|

Academic Leadership Development

(ALD) Program at College of Medicine, Jeddah;

King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health

Sciences

Saad

Abdulrahman Alghmdi (1)

Wesam Abuznadah (2)

Almoutaz Alkhier Ahmed (3)

(1) Dr. Saad Abdulrahman Alghamdi,

Consultant community medicine. SBCM, ABCM, MSc

in medical education.

National Guard Health Affairs, WR

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2) Dr.Wesam Abuznadah, Associate Dean, Academic

& Students Affair;

College of Medicine-Jeddah,

King Saud Bin Abdul-Aziz University for Health

Sciences

3) Dr.Almoutaz Alkhier Ahmed, Family medicine

Senior specialist and diabetologist

National Guard Specialized Polyclinics. National

Guard Health Affairs, WR

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence:

Dr. Saad Abdulrahman Alghamdi,

Consultant community medicine. SBCM, ABCM, MSc

in medical education.

National Guard Health Affairs, WR

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Email: drsaad32@gmail.com

|

Abstract

Introduction:

The new Medical College in Jeddah (COM-J)

- a branch of King Saud bin Abdulaziz

University for Health Sciences - is currently

confronting many challenges, accelerating

the need for effective academic leaders.

Unfortunately, little is known about how

the competency of academic leaders underpins

effective performance or how leaders might

be aided in acquiring competency. This

environment has driven authorities at

COM-J to be proactive in the establishment

of the Academic Leadership Development

(ALD) program for current and potential

future academic leaders.

Objectives: To assess the perception

of academic leaders on the importance

of capability, different approaches and

criterion for judging effective performance.

Methodology: A cross-sectional

online survey was conducted with 47 academic

leaders at COM-J. In addition to demographic

data, information on academic leaders'

perception of the importance of three

datasets (capabilities, approaches and

judging criteria) was collected using

a five-point Likert scale (1 - low to

5 - high). The project team and experts

in the field of leadership development

assessed the face validity of the survey

instrument. The reliability of the survey

instrument was calculated; Cronbach's

coefficient alpha was 0.97 (a high value).

Program Model: In response to the

need mentioned in the introduction, we

have adopted a model of academic leadership

development that has already been tested

in several large-scale studies of effective

leadership in higher education.

This model suggests an ongoing process

with 4 stages; Diagnosis, Development,

Implementation and Evaluation. Areas of

good practice are retained, and those

requiring further attention and new gaps

for development are re-addressed.

Results: The response rate was

100% (47), and the academic leaders perceived

that a combination of emotional intelligence

(both personal and interpersonal), cognitive

capabilities and a set of relevant skills

and knowledge are necessary for effective

performance as an academic leader at COM-J.

Conclusion:

We

produced a model for an ALD program at

COM-J with the following attributes:

• A set of capabilities and competencies

for effective leadership at COM-J.

•

A

set of quality checkpoints (criterion

for judging effective performance) at

COM-J.

•

An

online tool to enable future leaders to

complete the same survey and compare their

responses.

Key words: Education, leadership

|

Leadership development can be described as

the "longitudinal process of expanding

the capacities of individuals, groups, and organizations

to increase their effectiveness in leadership

roles and processes" (1).

Academic leadership is critical in higher education

because it influences the quality of student

learning (2). In Saudi Arabia, the Ministry

of Higher Education and leading Saudi universities

have recognized that leadership plays a significant

role in the success, effectiveness and quality

of higher education. Thus, the Ministry established

the Academic Leadership Center (ALC) in 2009

to give focus and emphasis to this critical

issue. Based on an initial plan, the ALC organized

numerous developmental activities to serve some

of the needs of Saudi higher education institutions

and administrators. These activities included

successful workshops for rectors, vice rectors,

academic deans and department chairs (3).

The new Medical College in Jeddah (COM-J) -

a branch of King Saud bin Abdulaziz University

for Health Sciences - is confronting many challenges,

which accelerates the need for effective academic

leaders. Unfortunately, little is known about

how the competency of academic leaders underpins

effective performance or how leaders might be

aided in acquiring competency. This environment

has driven authorities at COM-J to be proactive

in the establishment of the Academic Leadership

Development (ALD) program for current and potential

future academic leaders.

Middlehurst et al (4) question is there a difference

between leadership in higher education and other

organizations; they believe that there is no

difference (4).

Bryman (5) reviewed literature to determine

effective leadership styles in HE and found

that as there is no consistency in the literature

in using key terms it was difficult to form

a cumulative view (Bryman, 2009).

Although leadership is widely distributed across

universities, it is often subject to 'a somewhat

individualistic and management approach' (6).

The literature shows that very limited professional

development has been provided for academic leaders.

For example, only three percent of over 2000

academic leaders surveyed in the United States'

national studies from 1990 to 2000 had leadership

development programs at their universities (7).

However, in some developed countries, attempts

have been made to provide support for the academic

leaders. For example, in the United States,

the American Council on Education has been offering

a series of general national workshops for more

than 40 years. In England, the Leadership Foundation

for Higher Education was founded in 2004 by

the UK government to provide support and advice

on leadership and management for all UK University

and higher education colleges. In Australia,

in 2007, the federal government funded the LH

Martin Institute for Higher Education Leadership

and Management to meet the need for high quality

leadership in higher education (8).

In higher education, a competency-based approach

is an effective tool for leadership development

(9). Scott et al. (10) proposed a model for

academic leadership development (increasing

a leader's capability) that is shown in Figure

1. This model suggests that professional learning

for academic leaders will follow an action learning

cycle that involves an ongoing process to identify

the "gaps" in one's capabilities using

the leadership scales and dimensions and then

addresses these gaps using a mixture of self-managed

learning, practice-based learning, and appropriately

timed and linked formal leadership development.

As this process unfolds, the results can be

monitored using effectiveness indicators, and

the quality of what has emerged can be evaluated.

Areas of good practice are retained, and those

requiring further attention and new "gaps"

for development are re-addressed. In this manner,

the cycle continues. It is critical to view

the process not only as cyclical but also as

heading somewhere significant based on the validated

capability and focus scales that are identified

in the current study.

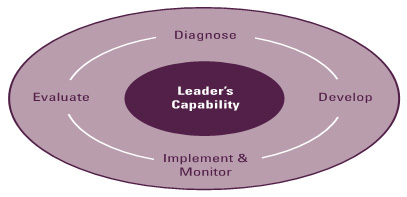

Figure 1: Model of Academic Leadership Development

In response to the above-stated needs, we adopted

this model, which has already been tested in

several large-scale studies of effective leadership

in higher education led by Geoff Scott, Hamish

Coates and Michelle Anderson (10)(13). However,

as Bryman (5) reported that any leadership framework

that ignores context is ineffective, a competency

model created in one context cannot be assumed

to be generalizable to other contexts. It was

therefore important to contextualize this model

for COM-J.

This project proposal began in April 2013 and

the needs assessment part of it, began in August

2013 and the main fieldwork was concluded in November

2014.

A range of background reviews were conducted -

reviews of research literature and policy reports,

and of operating environments to provide a vital

contextual dimension to the project. The survey

instrument was adopted from a prior study of higher

education leaders led by Geoff Scott, Hamish Coates

and Michelle Anderson (10)(13). Initially, insights

from the background reviews were used to refine

the instrument. The instrument was further revised

and enhanced, and then deployed in a data collection.

2.1 Study Setting:

The study was performed at the College of Medicine

in the King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for

Health Sciences, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. These

classes were located within King Abdulaziz Medical

City, National Guard Health Affairs. Classes began

in the academic year (2010/2011 - 1431/1432) and

adopted problem-based learning curriculum. Currently,

there are 143 students and 128 (joint 106 &

22 full-time) faculty staff.

2.2 Study Population:

This study limited its definition of leaders to

people in academic roles, representing people

who are positioned as formal leaders at COM-J.

A total of 47 academic leaders - the entire population

- were included: one dean, three associate deans,

five chairmen, thirty block coordinators and co-coordinators,

and eight college council members.

2. 3 Study Design:

In this cross-sectional study, an online survey

was conducted for 47 academic leaders focusing

on the following:

1. Part 1: Academic leaders' relevant

demographic data

2. Part 2: Academic leaders' perception

of the relative importance of sets of leadership

capabilities to identify priority areas:

•

Personal capabilities

•

Interpersonal capabilities

•

Cognitive capabilities

•

Leadership competencies

3. Part 3: Academic leaders'

perception of the relative effectiveness of

different approaches to developing these capabilities

4. Part 4: Academic leaders' perception

of indicators that can be used to evaluate their

effectiveness

The respondents quantitatively rated the importance

of items using a five-point Likert scale (1

- low to 5 - high). The target leaders were

invited by email to participate in the survey

and were given an explanation of the survey's

purpose and significance. Follow- up emails

were sent at weekly intervals, and the researcher

undertook personal follow-up when necessary.

The survey was field-tested before distribution

and was designed for online completion in approximately

20 minutes using a Qualtrics online survey.

The responses were confidential and were not

linked to information on the sampling frame.

The data collection was completed by early November

2013.

2.4 Data Management and Analysis

The data analysis addressed each of the study's

objectives and included a summary of the means

and ordinal ranks across the academic roles.

2.5 Validation & reliability

This model has already been validated in large-scale

studies, as previously noted. The project team

and one expert assessed the validity of the

instrument. The reliability of the survey instrument

was calculated: Cronbach's coefficient alpha

was 0.97 (a high value) for all questions, and

each individual question varied from 0.8 to

0.93.

2.6 Ethical Considerations:

The nature of this project highlights many ethical

issues, these are:

1) Get an official approval from the Master

Program of medical education; Department of

Medical education ; college of medicine ; king

Saudi bin Abdulaziz University for health science

(KSAU - HS)

2) Get Approval from COM-J authority to conduct

this project.

3) Confidentiality - Because academic leaders

may be sharing very personal information. Participants

should not normally be named (unless their permission

has been explicitly sought, and this should

only be done where a name is essential for the

pursuit of the research in question).

4) Informed consent - part of the online survey.

This usually required that respondents agreeing

to participate, after being informed of potential

risks and benefits.

5) Promises and reciprocity - The issue here

is what the participants get in return for sharing

their time and insights.

The

main

results

will

be

divided

into

three

parts

including

the

leader's

capability

model,

approaches

for

academic

leadership

development

at

COM-J,

and

criterion

for

judging

effective

performance.

3.1

Leader's

Capability

Model

Leaders'

capability

consists

of

five

domains

as

seen

in

Figure

2.

Each

domain

was

given

operational

definitions

by

an

inventory

of

56

items.

Furthermore,

these

items

were

clustered

into

11

different

scales.

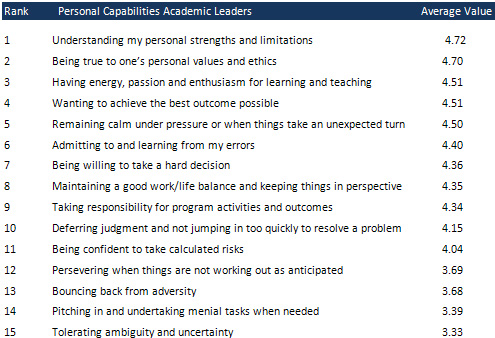

3.1.1

Domain

1:

Personal

Capability

Academic

leaders

particularly

emphasized

the

importance

of

the

following:

understanding

personal

strengths

and

limitations;

being

true

to

one's

personal

values

and

ethics;

having

energy,

passion

and

enthusiasm

for

learning

and

teaching;

wanting

to

achieve

the

best

outcome

possible;

and

remaining

calm

under

pressure

or

when

things

take

an

unexpected

turn.

Less

emphasis

was

given

to

facets

of

effective

leadership

that

involved

tolerating

ambiguity

and

uncertainty.

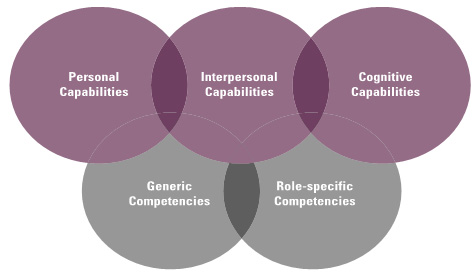

Figure

2:

Academic

Leadership

Capability

Domains

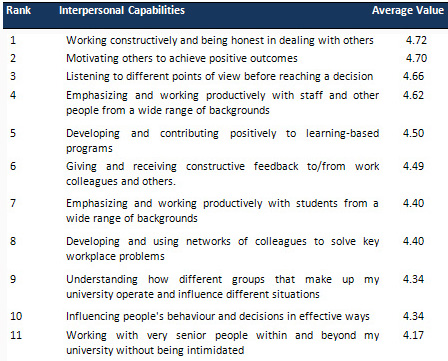

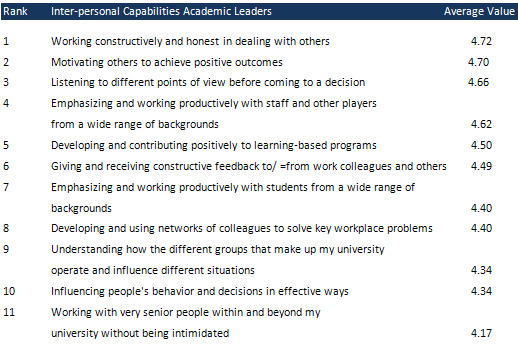

3.1.2

Domain

2:

Inter-Personal

Capability

Table

1

reports

the

importance

ratings

for

the

interpersonal

capabilities

items.

All

are

rated

highly

Table

1:

Interpersonal

capabilities

of

all

academic

leaders

at

College

of

Medicine,

Jeddah

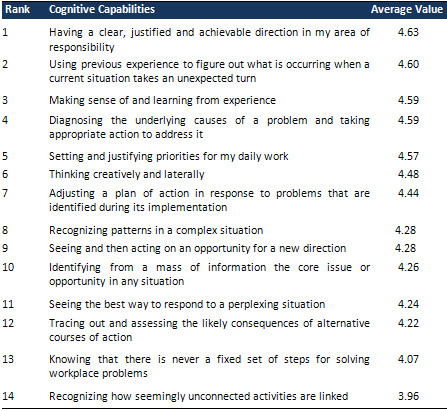

3.1.3

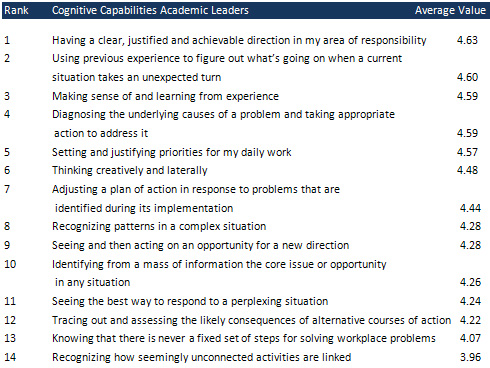

Domain

3:

Cognitive

capabilities

All

items

used

to

measure

the

cognitive

dimension

of

leadership

capability

were

rated

highly

by

the

COM-J

leaders

Table

2.

Table

2:

Cognitive

Capabilities

of

all

Academic

Leaders

at

College

of

Medicine,

Jeddah

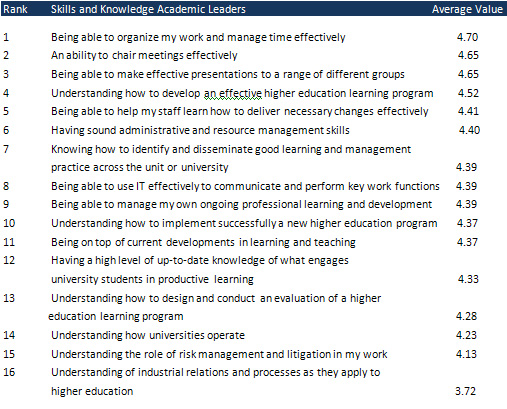

3.1.4

Domains

4

and

5:

Leadership

competencies

All

leadership

competencies

are

ranked

highly

(mean

above

4)

with

the

exception

of

competency

associated

with

understanding

of

industrial

relations

and

processes

as

they

apply

to

higher

education.

The

highest

levels

of

importance

were

attached

to

the

following:

Being

able

to

organize

work

and

manage

time

effectively;

the

ability

to

chair

meetings

effectively;

being

able

to

make

effective

presentations

for

a

range

of

different

groups;

the

comprehension

for

how

to

develop

an

effective

higher

education

learning

program;

and

being

able

to

help

staff

learn

how

to

deliver

necessary

changes

effectively.

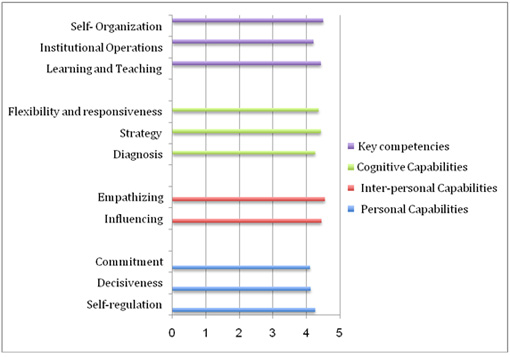

3.1.5

All

the

Domain

Scales

The

academic

leaders

perceived

that

all

the

domains

of

the

leader's

capability

model

were

important

for

effective

leadership

at

COM-J.

The

average

scores

of

the

scales

within

the

main

domains

are

reported

in

Figure

3.

Figure

3:

Leadership

Capability

Importance

(average

scale

score)

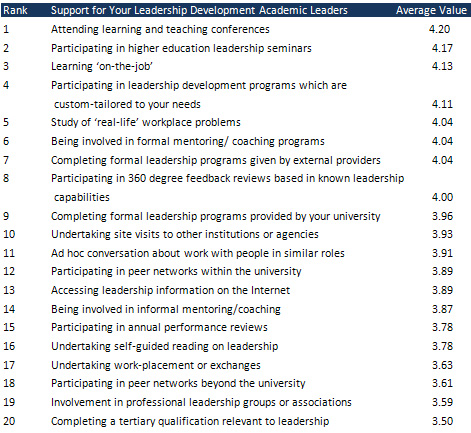

3.2

Approaches

for

academic

leadership

development

at

COM-J.

The

47

academic

leaders

were

asked

to

rate

the

effectiveness

of

each

of

the

learning

approaches

in

assisting

their

development

as

an

academic

leader

(1

[low]

to

5

[high]).

In

general,

the

leaders

at

COM-J

expressed

a

preference

for

attending

learning

and

teaching

conferences,

participating

in

higher

education

leadership

seminars,

learning

'on-the-job',

and

participating

in

leadership

development

programs

that

are

tailored

to

their

needs

more

than

completing

formal

leadership

programs

given

by

external

providers

or

even

by

the

university.

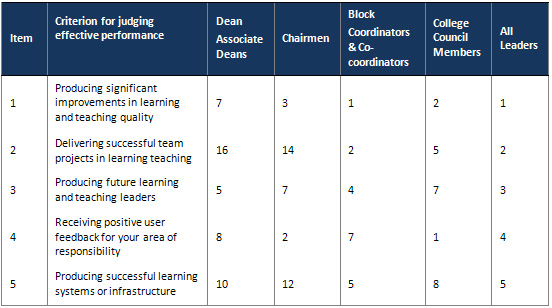

Table

3:

Indicators

of

Leadership

Effective

Performance

by

role

(items

ranks)

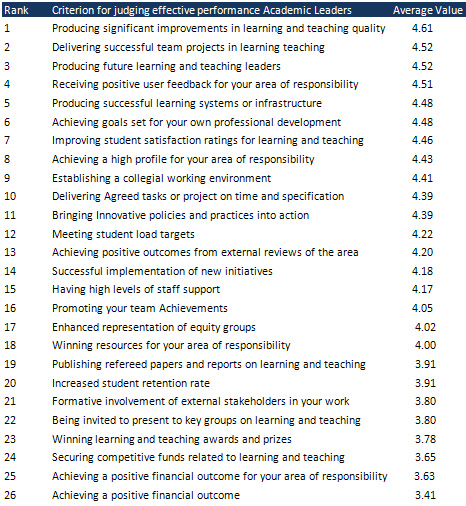

Only

the

first

5

ranks

are

reported

here

out

of

26

indicators.

In

this

study,

respondents

were

asked

to

rate

the

importance

of

each

indicator

as

a

criterion

for

judging

effectiveness

in

their

role.

There

were

26

indicators

ranked

by

leader

roles.

The

results

of

the

survey

of

the

whole

group

(all

academic

leaders)

1)

Personal

Capability

of

all

academic

leaders

at

COM-J

2)

Inter-personal

Capabilities

of

all

academic

leaders

at

COM-J

3)

Cognitive

Capabilities

of

all

academic

leaders

at

COM-J

4)

Skills

and

Knowledge

of

all

academic

leaders

at

COM-J

5)

Support

for

Leadership

(all

academic

leaders

at

COM-J)

6)

Criterion

for

judging

effective

performance

of

academic

leaders

Establishing

a

competency-based

model

for

the

ALD

program

at

COM-J

will

follow

Kern's

six-step

approach:

problem

identification,

general

needs

assessment,

targeted

needs

assessment,

goals

and

objectives,

program

strategies,

implementation

and

evaluation.

This

study

constitutes

the

general

needs

assessment

step

of

the

project.

The

model

adopted

in

this

program

has

been

validated

in

large-scale

studies

not

only

in

Australia

but

also

in

Canada,

the

United

Kingdom

and

South

Africa,

where

international

review

workshops

were

conducted.

The

face

validity

and

reliability

were

assessed

and

calculated,

and

high

levels

were

found.

Leaders

must

be

able

to

manage

their

own

emotional

reactions,

and

this

ability

reflects

their

personal

capability.

It

is

also

important

to

have

a

high

level

of

interpersonal

capability

to

better

understand

what

is

occurring

and

to

determine

what

might

work

best

to

resolve

the

situation.

Both

personal

and

interpersonal

capabilities

have

been

extensively

researched

during

the

past

decade

by

researchers

such

as

Goleman

(11)

and

are

often

referred

to

as

a

leader's

"emotional

intelligence."

The

results

of

this

study

showed

a

strong

perception

of

the

importance

of

different

capabilities

for

effective

performance

for

all

academic

leaders

at

COM-J.

This

outcome

provides

an

important

form

of

contextualization

of

the

model

for

COM-J.

Effective

leadership

does

not

merely

involve

capability.

Leading

organizations

such

as

COM-J

also

require

both

generic

and

specific

knowledge

and

skills

-

the

bottom

circles

in

Figure

2.

These

areas

of

competency

provide

support

for

diagnosing

different

situations

and

are

also

a

source

for

shaping

and

delivering

the

appropriate

response.

Therefore,

all

five

domains

must

function

in

an

integrated

and

productive

manner

over

time.

Thus,

a

weakness

in

one

area

affects

the

operation

of

other

areas.

The

contribution

of

this

study

is

to

help

academic

leaders

to

develop

skills

that

are

important

for

the

effectiveness

of

academic

leadership.

Evidence

from

the

47

leaders

who

participated

in

this

study

affirms

that

effective

leadership

involves

both

individual

talent

and

a

situated

capacity

for

implementation.

Clearly,

professional

learning

is

not

essential

for

leadership

-

many

leaders

have

little

formal

training

in

leadership

prior

to

assuming

their

roles,

although

they

perform

well.

However,

leadership

training

is

a

helpful

and

undoubtedly

valuable

means

of

ensuring

high-quality

leadership.

Unless

academic

leadership

development

programs

are

implemented

properly

with

the

appropriate

approaches,

they

will

fail.

Therefore,

to

ensure

that

our

ALD

program

will

utilize

the

appropriate

approaches

for

implementation,

the

47

academic

leaders

completing

the

online

survey

were

asked

to

rate

the

effectiveness

of

each

of

the

learning

approaches

in

assisting

their

development

as

an

academic

leader.

If

we

compare

the

results

of

this

study

with

those

of

Scott

(10)

and

Coates

(12).

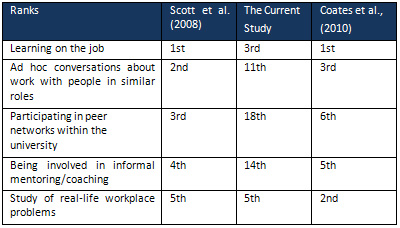

The

table

below

shows

that

learning

on

the

job

and

the

study

of

real-life

workplace

problems

were

within

the

first

five

rankings

in

all

the

studies.

Although

ad

hoc

conversations

about

work

with

people

in

similar

roles,

participation

in

peer

networks

within

the

university

and

involvement

in

informal

mentoring/coaching

were

not

within

the

first

five

ranks

of

preferred

approaches

at

COM-J,

the

results

still

indicate

the

need

for

this

program,

as

the

environment

is

currently

not

supporting

such

approaches.

Establishing

a

competency-based

model

for

the

ALD

program

at

COM-J

will

follow

Kern's

six-step

approach:

problem

identification,

general

needs

assessment,

targeted

needs

assessment,

goals

and

objectives,

program

strategies,

implementation

and

evaluation.

This

study

constitutes

the

general

needs

assessment

step

of

the

project.

1.

We

limited

the

definition

of

academic

roles

to

those

who

are

positioned

as

formal

leaders,

but

there

are

likely

to

be

others

who

are

engaged

in

informal

leadership

positions.

Although

this

definition

is

behind

the

scope

of

this

study,

there

would

be

value

in

further

work

to

review

the

nature

and

effects

of

informal

leadership

at

COM-J.

2.

This

study

for

the

contextualization

of

the

model

to

COM-J

employed

a

quantitative

approach;

thus,

qualitative

studies

are

needed.

The

study

conducted

within

this

project

indicates

that

effective

performance

as

an

academic

leader

at

COM-J,

requires

the

combination

of

emotional

intelligence

(both

personal

and

interpersonal),

cognitive

capabilities

and

a

particular

set

of

relevant

skills

and

knowledge.

This

result

serves

to

confirm

the

conceptual

model

summarized

in

Figure

2.

The

results

are

also

consistent

with

those

of

parallel

studies

that

have

used

the

same

framework

(10).

1.

The

ALD

program

should

be

aligned

with

the

findings

of

this

study

with

regard

to

what

and

how

academic

leaders

prefer

to

learn.

2.

Further

qualitative

studies

using

semi-structured

interview

or

focus

groups

for

the

same

population

with

Scott,

Coates

and

Anderson's

(10)

conceptual

model

for

higher

education

leadership

capability

as

a

guide

are

required

to

improve

our

understanding

and

to

gain

a

rich

picture

of

leadership

at

COM-J.

3.

The

final

capability/competency

model

resulting

from

further

qualitative

studies

can

be

integrated

with

other

human

resource

practices

to

create

the

following:

i.

Hiring

guidelines

ii.

Job

descriptions

iii.

Promotion

criteria

iv.

Performance

appraisal

1)

Day

D.

V.,

&

Harrison,

M.

M.

A

multilevel,

identity-based

approach

to

leadership

development.

Human

Resource

Management

Review,

17(4),

360-373.2007

2)

Ramsden,

P.,

Prosser,

M.,

Trigwell,

K.,

&

Martin,

E.

University

teachers'

experiences

of

academic

leadership

and

their

approaches

to

teaching.

Learning

and

Instruction,

17(2),

140-

155.

2007

3)

Academic

leadership

center.

Ministry

of

Higher

Education,

Saudi

Arabia.

Retrieved

from

http://

http://www.alc.edu.sa.

2013

4)

Middlehurst,

R.,

Goreham,

H.,

&

Woodfield,

S.

Why

Research

Leadership

in

Higher

Education?

Exploring

Contributions

from

the

UK's

Leadership

Foundation

for

Higher

Education.

Leadership,

5(3),

311-329

.

2009

5)

Bryman,

A.

Effective

Leadership

In

Higher

Education.

London:

Leadership

Foundation

for

Higher

Education.

2009

6)

Bolden,

R.,

Petrov,

G.,

&

Gosling,

J.

Distributed

Leadership

in

Higher

Education:

Rhetoric

and

Reality.

Educational

Management

Administration

Leadership,

37(2),

257-277.

2009

7)

Gmelch,

W.

H.

The

department

chair's

balancing

acts.

New

Directions

for

Higher

Education

126,

16.2004

8)

Thi

Lan

Huong

Nguyen

(2012):

Identifying

the

training

needs

of

Heads

of

Department

in

a

newly

established

university

in

Vietnam,

Journal

of

Higher

Education

Policy

and

Management,

34:3,

309-321

9)

Spendlove,

M.

(2007),

Competencies

for

effective

leadership

in

higher

education.

International

Journal

of

Educational

Management,

21(5),

407-417

10)

Scott,

G.,

Coates,

H.,

&

Anderson,

M.

(2008).

Learning

leaders

in

times

of

change:

Academic

leadership

capabilities

for

Australian

higher

education.

11)

Goleman,

D.

(1999).

Working

with

Emotional

Intelligence.

Bloomsbury

Publishing.

12)

Coates,

Hamish

Bennett;

Meek,

V

Lynn;

Brown,

Justin;

Friedman,

Tim;

Noonan,

Peter;

and

Mitchell,

John,

"VET

Leadership

for

the

Future:

contexts,

characteristics

and

capabilities"

(2010).

http://research.acer.edu.au/higher_education/13

13)

Anderson

&

Johnson,

(2006),

Ideas

of

leadership

underpinning

proposals

to

the

Carrick

Institute:

A

review

of

proposals

from

the

'Leadership

for

Excellence

in

Teaching

and

Learning

Program'

|