|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor)

DOI:10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93610

|

........................................................

|

|

Editorial

Dr.

Abdulrazak Abyad

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93623

Original Contribution

Self-monitoring

of Blood Glucose Among Type-2 Diabetic Patients:

An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study

[pdf]

Ahmed S. Alzahrani, Rishi K. Bharti, Hassan

M. Al-musa, Shweta Chaudhary

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93624

White

coat hypertension may actually be an acute phase

reactant in the body

[pdf]

Mehmet Rami Helvaci, Orhan Ayyildiz, Orhan Ekrem

Muftuoglu, Mehmet Gundogdu, Abdulrazak Abyad,

Lesley Pocock

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93625

Case Report

An

Unusual Persistent Mullerian Duct Syndrome in

a child in Abha city: A Case Report

[pdf]

Youssef Ali Mohamad Alqahtani, Abdulrazak Tanim

Abdulrazak, Hassa Gilban, Rasha Mirdad, Ashwaq

Y. Asiri, Rishi Kumar Bharti, Shweta Chaudhary

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93628

Population and Community

Studies

Prevalence

of abdominal obesity and its associated comorbid

condition in adult Yemeni people of Sana’a

City

[pdf]

Mohammed Ahmed Bamashmos

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93626

Smoking

may even cause irritable bowel syndrome

[pdf]

Mehmet Rami Helvaci, Guner Dede, Yasin Yildirim,

Semih Salaz, Abdulrazak Abyad, Lesley Pocock

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93629

Systematic

literature review on early onset dementia

[pdf]

Wendy Eskine

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93627

|

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

AUSTRALIA

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| March 2019 - Volume

17, Issue 3 |

|

|

Early Onset Dementia: A Systematic

Review of the Literature to Inform Qualitative

Experiences

Wendy Erskine

Correspondence:

Wendy

Erskine BA, LLB, A.B.P.I., M.Litt PhD.

St Andrews,

Fife,

Scotland

Email: wendy.erskine2014@gmail.com

Received: January 2019; Accepted: February

2019; Published: March 1, 2019

Citation: Wendy Erskine. Early Onset Dementia:

A Systematic Review of the Literature to Inform

Qualitative Experiences. World Family Medicine.

2019; 17(3): 34-58. DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93627

|

Abstract

There is increasing recognition that EOD

(Early Onset Dementia) represents an important

social problem affecting economic and

social impacts (Campbell et al., 2008;

Johannessen et al., 2018). Recent research

calls for greater efforts to be made in

consulting with the PwD (people with dementia)

directly (Allen 2001; Bamford & Bruce

2000). The condition is understood to

occur between the ages of 45-65 (Mercy,

2008). This makes EOD a sub-group of dementia

with numerous differences when compared

to later onset dementia. These include

the likelihood of still being in work

and having a family to raise. Being responsible

for an income and for dependent others

is particularly difficult for those affected.

Additionally, the social and psychological

context for younger people is different

(Beattie, 2004). PwEOD (people with Early

Onset Dementia) are more likely to be

physically fitter than those with later

onset dementia which may impact on their

physical care needs. The existing expectation

within health and social care agencies

for PwEOD is in keeping within an older

person’s framework of care which

may well be inappropriate. This may have

occurred in the past due to biomedical

assumptions regarding the condition (Kitwood,

1997; van Vliet et al., 2017). This also

suggests that little attention has been

paid to subjective experiences (van Vliet,

2017). The need to elicit the views and

subjective experiences of PwEOD is therefore

gaining increasing recognition within

health and social care research (van Vliet,

2010). Literature has been modestly growing

in the subject area to demonstrate how

PwEOD have expressed their views and experience

of dementia successfully (Page and Keady,

2010; Ohman et al., 2001). However, most

of the extant literatureis based on family

carers (Cabote, 2015; Kobiske and Bekhet,

2018). Whilst carers’ views are important

they should not be used as a substitute

for the views of younger people with dementia

(Goldsmith 1996, Whitlatch 2001). Given

the limited research available, both the

views of PwEOD and their family carers

are incorporated into the systematic literature

review.

Key words:

Early onset dementia (EOD), qualitative,

people with early onset dementia (PwEOD),

family kin, meta-ethnography, stigma,

liminality and chronicity, biographical

disruption, losses, coping

|

Personal accounts describing EOD have potential

to inform clinical and care provision as well

as informing other dementia subsets. Examining

first person accounts makes this a valuable

exercise. This may be assumed as PwEOD (People

with Early Onset Dementia) possess more faculties

with which to tell about lived experience from

first person accounts.

Study

aim:

This

systematic

review

paper

sought

to

address

the

following

question:

‘How

do

PwEOD

as

a

diagnosed

sub

group

of

other

dementias

and

their

immediate

family

experience

living

with

EOD?’

Study

inclusion:

Studies

were

included

and

excluded

according

to

the

following

criteria:

a

diagnosis

of

EOD

between

the

ages

of

45-65

[1];

research

dated

between

1998-2018;[2]

in

English

language;

qualitative

and

peer

reviewed

papers.

The

key

aim

of

study

inclusion

was

to

capture

the

experience

of

living

with

EOD

through

the

available

literature

in

the

field.

Personal

experiences

were

sought

in

the

literature

on

PwEOD

and

their

immediate

family

living

with

the

experience

post-diagnosis.

The

scoping

review

uncovered

the

relative

lack

of

studies

to

date

on

the

experiences

of

PwEOD,

therefore

studies

were

inclusive

of

spouses,

partners,

children

and

adult

dependents

as

people

living

with

the

PwEOD.

Searches

were

kept

broad

and

unconstrained

by

further

filters

in

order

to

capture

a

fuller

picture

of

the

issues

and

experiences

connected

to

EOD.

Study

exclusion:

Studies

focusing

solely

on

people

presenting

with

dementia

younger

than

45;

studies

with

a

predominant

interest

in;

dementia

caused

by

HIV,

traumatic

brain

injury,

Down’s

syndrome,

congenital

birth

conditions

likely

to

include

dementia,

Huntington’s

chorea

and

alcohol-related

dementia

were

excluded.

Systematic

literature

reviews

were

excluded.

Scoping:

A

scoping

exercise

of

the

literature

took

place

prior

to

the

systematic

literature

review

which

identified

EOD

as

a

sub-group

of

dementia

under-represented

in

the

literature.

Google

Scholar

and

Abertay’s

Library

Search

including

serendipitous

searches

using

prior

knowledge

of

the

research

field

extended

the

search

in

preparation

for

the

systematic

review.

Search

strategy:

The

author

then

searched

databases

which

were

selected

for

their

social

and

clinical

perspectives

through

EBSCOhost;

Web

of

Science

and

Cinahl

plus

with

text,

Psychology

and

Behavioural

Sciences

Collection,

Scopus

and

Sage.

The

search

terms

were:

dement*,

early

onset

dementia,

young

onset

dementia,

presenile-Alzheimer*

and

working

age

dementia.

These

were

searched

as

single

terms

using

Boolean

phrasing;

‘OR’

then

once

the

searches

were

captured,

refined

with;

‘AND’

then

stored

for

scrutiny

at

the

next

stage.

Selection

of

papers:

The

search

located

five-hundred-and-fifty-two

(522)

papers.

Duplicates

were

removed

(n=22).

The

remaining

studies’

(n=500)

abstracts

and

titles

were

screened.

Twenty-two

studies

(n=22)

were

retained

and

full

texts

read.

This

left

sixteen

studies

(n=16)

to

be

included.

The

reference

lists

of

the

twenty-two

studies

were

also

examined.

Although

two

were

added

from

references,

they

were

finally

excluded

for

failing

to

meet

the

criteria.

With

reference

to

the

final

six

studies

excluded,

these

are

listed

in

the

appendices

(Appendix

1).

Approach

to

systematic

and

meta-analysis

synthesis

of

studies

The

review

was

guided

by

the

systematic

approach

preferred

by

PRISMA

(Reporting

Systematic

Reviews

and

Meta-Analysis

Studies

(Liberati,

2009).

Figure

1

illustrates

the

process

of

papers

being

excluded

or

included

for

the

systematic

review

based

upon

the

study

question.

This

process

sets

a

standard

for

the

assessment

and

critique

of

health

focussed

studies

and

interventions

assisting

the

processes

for

summarising

evidence

accurately

and

reliably.

However,

it

is

the

case

that

the

methods

of

meta-analysis

are

not

transferable

to

qualitative

health

research

for

a

number

of

pragmatic

and

epistemological

reasons;

for

example,

computer

literature

searches,

statistical

data

and

priorities

in

quantitative

research

may

fail

to

capture

forms

of

qualitative

research

which

lack

the

appeal

of

more

clinical

protocols

and

interventions

(Britten

et

al.,

2002).

As

such,

criteria

for

judging

the

quality

of

published

research

whilst

contested

in

the

past

have

since

found

established

qualitative

protocols

for

comparing

studies

(Britten

et

al.,

2002).

The

potential

audiences

for

viewing

research

through

this

lens

include

practitioners

across

a

broad

health

practice

background

as

well

as

policy-makers

and

qualitative

researchers

(Britten

et

al.,

2002).

Therefore,

there

exists

several

well

recognised

methods

by

which

to

conduct

a

systematic

review

of

qualitative

literature

(Greenwood

&

Smith,

2016).

The

role

of

meta-ethnography

in

qualitative

research

The

impetus

for

developing

methods

of

qualitative

synthesis

has

arisen

from

a

need

to

complement

quantitative

research.

This

looked

to

gain

a

more

complete

understanding

of

phenomena,

especially

in

terms

of

organisational

processes

and

provision

of

services

(Greenhalgh,

1998).

Therefore

a

need

existed

to

bring

together

isolated

studies

for

comparison

(Sandelowski

et

al.,

1997).

Meta-ethnography

provides

a

way

to

compare

qualitative

studies

accommodating

induction

and

interpretation

(Greenwood

&

Smith,

2016).

It

also

can

synthesise

conceptual

innovations

such

as

metaphorical

and

emotionally

relevant

phenomena

(Strike

and

Posner,

1983).

It

has

origins

in

the

interpretive

paradigm

and

as

such,

it

possesses

an

alternative

to

traditional

aggregative

methods

of

synthesis

which

retain

qualities

or

concepts

of

the

qualitative

method

of

study

it

aims

to

synthesise.

The

benefit

of

applying

meta-ethnography

to

the

synthesis

of

qualitative

research

and

suitability

for

this

study

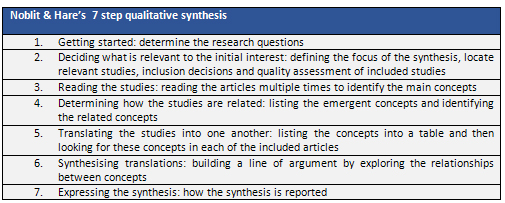

was

informed

by

Noblit

and

Hare’s

(1988)

seven-step

process

(Table

1).

Narrative

literature

reviews

capture

concepts

and

information

in

a

more

eclectic

fashion

but

have

in

the

past

been

criticised

for

being

singular

descriptive

accounts

based

upon

the

implicit

bias

of

the

researcher

(Fink,

1998).

They

have

also

been

condemned

for

lacking

critical

assessment.

Adopting

a

more

systematic

approach

to

the

literature

was

therefore

useful

in

order

to

approach

a

more

comprehensive

contemporary

review

of

the

field.

This

approach

was

particularly

helpful

in

investigating

EOD

as

a

lesser

known

sub-group

of

dementia.

Meta-ethnography

has

proven

a

sound

technique

for

synthesising

qualitative

research

in

health

studies

(Paterson

et

al.,

1998).

It

has

been

successfully

employed

in

publications

to

date

including:

lay

meanings

of

medicines

(Britten

et

al.,

(2002);

lay

experiences

of

diabetes

and

diabetes

care

(Campbell

et

al;

2003);

what

values

people

seek

when

they

provide

unpaid

care

for

an

older

person

(Al-Janabi

et

al.,

2008)

and

locating

how

coping

experiences

appear

in

chronic

fatigue

syndrome

sufferers

(Larun

and

Malterud,

2007).

[1]

This

definition

is in

keeping

with

Mercy

(2008),

excluding

two

other

studies

limiting

EOD

to 45-60.

All

others

searched

for

the

systematic

review

including

the

scoping

review

referred

to 45-65

as the

most

commonly

used

criteria

for

EOD.

[2]

Searches

between

1998-2018

captured

the

advent

and

widespread

prescription

of anti-cholinesterase

inhibitor

treatment

and

linked

with

a key

driver

as laid

out

in the

Scottish

Government’s

2009

report

making

dementia

a healthcare

priority

for

development.

Table

1:

Click

here

for

Figure

1:

PRISMA

flowchart

Participant

and

study

design

The

inclusion

criteria

sought

studies

spanning

1998-2018.

However,

the

studies

ranged

from

2009

to

2018.

The

mean

date

was

2015.

All

studies

were

performed

in

Western

countries

(Norway-6;

America-1;

England-;

6;

The

Netherlands-1;

Ireland-1

&

Australia-1).

Where

English

was

not

the

dominant

language

it

was

widely

taught

and

well

spoken

(Norway

and

The

Netherlands).

The

participants

were

predominantly

drawn

from

health

environments

or

services

structured

to

assist

PwD

or

PwEOD

such

as

statutory

or

voluntary

bodies.

There

were

a

total

of

229

participants

after

making

amendments

for

those

participants

drawn

from

the

same

sample

groups

where

multiple

study

authors

were

included.

Johannessen

et

al.,

(2014)

and

Johannessen

and

Moller

(2011)

used

the

same

participants.

Johannessen

et

al.,

(2016)

and

Johannessen

et

al.,

(2017)

also

shared

participants

databases

throughout

the

studies.

Data

were

collected

through

face

to

face

interview

mostly

using

a

semi-structured

format.

These

were

situated

within

the

statistics

of

the

studies

quoted

above;

(PwEOD

(4);

their

family

members

(2);

both

spouses

(2)

and

dependents

(8)

whether

still

regarded

as

children

living

at

home

or

adult

children

living

independently

elsewhere).

These

studies

drew

together

the

theoretical

approaches

to

the

data

founded

in:

grounded

theory

(5);

autobiographical

life

story

narrative

(3);

phenomenological

hermeneutic

analysis

(2);

Thematic

Analysis

(TA)

(2);

qualitative

semi

structured

interview

(1);

conceptual

model

(1);

action

research

study

(1)

Interpretative

phenomenological

analysis

(IPA)

(1).

Ethnicity

was

referred

to

infrequently

(n=1)

and

where

ethnic

origins

were

detailed,

the

sample

groups

were

white/Western.

Allen

et

al.,

(2009)

was

the

only

study

to

include

25%

Asian

participants

within

an

English

sample.

Other

studies

made

no

attempt

to

refer

to

ethnicity

and

so

a

presumption

is

made

that

natives

of

the

country

of

origin

satisfied

the

sample

cohorts.

This

is

excepting

Sikes

and

Hall

(2017)

which

reported

that

the

sample

participant

group

was

‘mainly

white,

British,

middle-class,

participants’.

Type

of

dementia

was

not

a

focus

except

for

Johannessen

et

al.,

(2017)

which

focused

on

people

with

fronto-temporal

lobe

dementia.

Other

data

reported

were

related

to

whether

participants

(both

PwEOD

and

family)

were

working,

living

at

home,

in

studies,

in

a

care

home,

retired

or

medically

signed

off

work

and

living

on

retirement

funds

or

state

benefits.

The

source

for

participants

overwhelmingly

arose

from

clinical

or

health

focused

environments.

This

particular

feature

was

examined

in

the

discussion

of

the

studies.

Having

noted

the

brief

characteristics

of

the

studies

above,

the

following

tables

and

sub-sections

developed

overall

themes

along

with

the

development

of

the

line

of

argument.

Click

here

for

Table

2:

Participant

and

study

design

Drawing

a

line

of

argument

from

the

seven

step

process

Noblet

and

Hare

(1988)

refer

to

a

meta-ethnographic

line

of

argument

which

emerges

to

articulate

a

larger

phenomenon

drawn

from

the

data.

This

was

achieved

by

following

the

steps.

After

selecting

an

aim

and

study

question

(steps

one

and

two),

the

studies

were

read

to

fulfil

step

three.

This

was

followed

by

populating

the

tables

with

typical

broad

characteristics

(Table

2).

Investigation

of

experiences

were

then

described

(Table

3).

Following

this,

steps

four,

five

and

six

produced

more

concepts

(Table

4)

and

themes

(Table

5)

were

populated

taking

care

to

ensure

the

data

remained

true

to

the

original

studies.

Step

seven

provided

for

a

discussion

through

the

line

of

argument

of

what

fresh

data

was

discovered.

Click

here

for

Table

3:

Investigation

of

experiences

Overall

themes

By

the

time

Table

five

was

completed

at

stages

five

and

six

in

accordance

with

Noblit

and

Hare’s

seven

step

process,

new

data

emerged

to

realise

conceptual

themes

crystallised

into

themes

which

formed

the

expression

of

the

new

information.

The

expression

of

the

synthesis

followed

the

tables

discussed

theme

by

theme.

Click

here

for

Table

4:

Conceptual

themes

Conceptual

themes

and

Schultz’s

first

and

second

order

constructs

The

table

below

concluded

the

development

of

the

line

of

argument.

Noblit

and

Hare

adopted

Schutz’s

notion

of

first

and

second

order

constructs

assisting

the

progression

of

themes.

Schutz

utilised

the

term

first-order

construct

in

referring

to

the

everyday

constructs

and

understandings

of

ordinary

lay

people.

The

second-order

construct

referred

to

those

constructs

familiar

to

social

science

researchers.

The

table

below

(Table

5)

reveals

how

the

themes

took

their

place

within

the

constructs

drawn

in

accordance

with

Schutz’s

terms.

The

final

themes

that

arose

were:

i)

biographical

disruption

ii)

diagnosis,

iii)

losing

life,

friends

and

competences,

iv)

liminality

and

chronicity,

v)

stigma,

and

vi)

coping

with

cautious

optimism.

The

table

below

finalised

the

creation

of

new

concepts

which

are

followed

by

discussion

of

the

themes.

Click

here

for

Table

5:

Second

and

third

order

interpretations

| | |