|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor) |

|

|

|

|

........................................................

|

Original

Contribution/Clinical Investigation

|

|

|

<-- Turkey -->

Preoperative

management of sickle cell patients with hydroxyurea

[pdf version]

Mehmet Rami Helvaci,

Sedat Hakimoglu, Mehmet Oktay Sariosmanoglu,

Suleyman Kardas, Beray Bahar, Merve Filoglu,

Ibrahim Ugur Deler, Duygu Alime Almali, Ozcan

Gokpinar, Ozlem Celik, Aynur Ozbay, Ozgun Ilke

Karagoz, Seher Aydin

<-- Ethiopia-->

Khat

(Catha edulis) chewing as a risk factor of low

birth weight among full term Newborns: A systematic

review

[pdf version]

Kalkidan Hassen

<-- Australia -->

Chronic

pain review following Lichtenstein hernia repair:

A Personal Series

[pdf

version]

Maurice Brygel,

Luke Bonato, Sam Farah

<-- Saudi Arabia -->

Assessment

of Health Status of Male Teachers in Abha City,

Saudi Arabia

[pdf

version]

Ali Mofareh Assiri,

Hassan M. A. Al-Musa

|

|

........................................................ |

Evidence

Based Medicine

........................................................

Medicine and Society

........................................................

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| October 2015 -

Volume 13 Issue 7 |

|

|

Assessment of Health

Status of Male Teachers in Abha City, Saudi

Arabia

Ali

Mofareh Assiri (1)

Hassan M. A. Al-Musa (2)

(1) MB BS, Saudi Board of Family Medicine

(2) MB BS, ABFM, Consultant & Associate

Professor

Chairman, Family and Community Medicine Department

College of Medicine, King Khalid University

Correspondence:

Dr. Hassan M. A. Al-Musa

Family and Community Medicine Department

College of Medicine,

King Khalid University

P.O. Box 641, Abha, K.S.A

Contact No.: 0501882929

Email: fcmcomkku@gmail.com;

almusa3@hotmail.com

|

Summary

This study was

done to assess the health aspect of male

teachers (384) and to assess level of

job satisfaction of male teachers in different

grades in Abha city.

Following a simple random sample, the

sample from primary 184 (47.9%), intermediate

132 (34.4%) and secondary 68 (17.7%) school's

male teachers in Abha City were selected.

All respondent teachers were exposed to

the validated questionnaire to assess

health problem [medical history and co-morbidities]

and work place risk factors.

The background data as age was 39.31 ±7.96[23:75]

years; the average experience years were

16.1 ±7.43[1:36] years and 71.6%

have experience more than 10 years. 100

% of the sample were males due to socio-cultural

matters, as regard to the educational

level 47.9% were from primary schools,

34.4% from intermediate schools and 17.7%

from secondary schools.

The level of satisfaction regarding current

job and salary of teachers revealed that

65.6% were satisfied while 34.4% were

not satisfied.

The answers about some medical history

like history of having medical problems

that affect teacher's ability (9.4%),

history of treatment in hospital (25.5%)

, sick leave 19% and all were within accepted

range, apart from seeing a doctor in last

year (43.2%).

The complaints or health problems among

teachers as regards eyesight problems

15.4%, Hearing problems in 6.5%, Mental

illness, psychological or psychiatric

problem was 7.8%. The history of drug

or alcohol problem was 2.3%, skin problems

12%, history of hepatitis or jaundice

1.6%. The heart or blood pressure problems

were 11.32%. The history of allergies

was 17.4%; asthma or chest problem was

reported in 20.8% and cough for more than

3 weeks, coughed up blood or had any unexplained

weight loss or fever, was 9.6%.

The history of Musculoskeletal disorders

(MSD) was 21.1%, Low back pain (LBP) 21.6%

and joint pain 32%. Regarding feeling

well and healthy 154 (32%) gave the answer

that they are NOT healthy or feeling well.

The relation between ill health and experience

years gave a significant association but

no significant association with teaching

level.

The relation between job satisfaction

and experience years showed no significant

difference with experience years, but

the higher rates with longer experience

(70.2%) and gave significant relation

with level especially at primary level.

|

Teachers' work today is multifaceted as they

undertake not only teaching but also matters

associated with curriculum, students, parents,

the school community and departmental initiatives

[1].

These are tough times to be a teacher. Emerging

issues of concern in the teaching profession

are attrition rates and burnout levels. Ewing

and Smith [2] reported that between 25% and

40% of beginning teachers in countries in the

Western World are leaving teaching or they are

burned out.

In Australia, a study [3] highlighted an upward

trend in early-career teacher resignations and

according to Macdonald [4] overall teacher attrition

in Australian government schools ranges from

3% to 8%. When this is considered in conjunction

with the impending teacher shortage in Australia

[5], it is important to determine how teachers

feel about their roles as this has implications

for meeting society's expectations for education

and for youth today; it also has implications

for teacher well-being.

Well-being, according to Dunn [6] involves comparative

private experiences with regard to self-perceived

quality of an individual's life; it also includes

both affective and cognitive components.

Factors that influence teacher well-being,

burnout and competence

Traditionally, the role of teaching has been

one of nurturing and developing students' potential;

teachers play a valuable role in helping children

grow. In order to do this they must remain physically

and mentally well [7]. However, there is apparent

dissonance between teachers' perceived capacities

and the expectations of their role. This may

have implications for their physical and mental

well-being and their professional competence

as teachers [8].

Teacher well-being and competence have been

related to job satisfaction and studies indicate

that those teachers who are less satisfied are

more likely to leave teaching. For example,

Singh and Billingsley [9] found factors such

as stress, burnout, work overload, and job dissatisfaction

contribute to teacher attrition while factors

such as administrative support, reasonable role

expectations, and decreased workplace stress

contribute to teachers' intention to stay in

teaching. Principals play a pivotal role in

steering the direction of their school which

requires guiding the day-to-day business of

the school including matters associated with

both students and teachers.

The Management of Health and Safety at Work

Regulations 1999 addressed various health hazards

to which teachers are exposed [10].

Fitness criteria

To be able to undertake teaching duties safely

and effectively, it is essential that individual

teachers: have the health and well-being necessary

to deal with the specific types of teaching

and associated duties (adjusted, as appropriate)

in which they are engaged; are able to communicate

effectively with children, parents and colleagues;

possess sound judgment and insight; remain alert

at all times; can respond to pupils' needs rapidly

and effectively; are able to manage classes

and do not constitute any risk to the health,

safety or well-being of children in their care.

Where disabilities exist, teachers should be

enabled by reasonable adjustments, to meet these

criteria. The decision on fitness should be

considered using the above criteria and should

be based on an individual's ability to satisfy

those criteria in relation to all duties undertaken

as part of their specific post and in relation

to all of the individual's health problems [11]

Saudi

Arabia

is

a

country

with

an

independent

monarchy

situated

in

South

West

Asia.

The

first

feature

of

the

educational

system

in

Saudi

Arabia

is

the

combination

of

different

international

education

systems

along

Islamic

lines.

The

Ministry

of

Education

(MOE)

was

founded

in

1954

as

a

replacement

to

the

Directory

of

Education.

It

is

the

responsible

body

for

educational

policy

development

of

the

curriculum

and

teaching

methods.

The

educational

system

is

highly

centralized,

and

decision

making

is

top-down.

General

education

is

divided

into

three

main

levels:

primary

level

for

six

years,

middle

level

for

three

years

and

secondary

level

for

three

years.

The

schools

in

each

city

of

Saudi

Arabia

come

under

the

responsibility

and

supervision

of

the

Educational

Administration

[12].

Due

to

the

importance

of

Education

in

the

Socio-Economic

development

of

an

individual,

great

efforts

are

always

made

to

ensure

that

an

individual

goes

through

the

Education

cycle

successfully

by

achieving

high

academic

results.

The

need

for

good

results

puts

every

stake-holder

in

the

Education

Sector

on

alert.

Many

mechanisms

are

put

in

place

to

ensure

high

performance

and

good

results.

Such

mechanisms

include:

introducing

performance

contracts

by

the

government,

initiation

of

Free

Primary

Education

(FPE)

and

Subsidizing

Secondary

Education

(SSE),

increasing

contact

hours

between

the

teacher

and

learner,

holiday

tuition,

remedial

teaching

during

weekends,

intensive

testing

policies

[13].

In

considering

implications

of

health

problems

for

an

individual's

fitness

to

teach,

it

is

important

to

recognize

that

some

teaching

duties

involve

exposure

to

potential

health

hazards.

The

risk

arising

from

such

hazards

will

vary

according

to

the

specific

nature

of

the

teaching

duties

and

the

environment

in

which

the

teacher

is

working.

Teacher

training

providers

and

employing

organizations

have

a

statutory

responsibility

to

safeguard

the

health,

safety

and

welfare

of

teachers,

to

conduct

risk

assessments

and

take

steps

to

address

potential

hazards

and

reduce

the

risk

of

adverse

health

effects.

Occupational

health

professionals

have

a

key

role

in

advising

organizations

in

this

regard

[10].

Physical,

Chemical,

Biological

Teachers

are

potentially

exposed

to

a

range

of

physical,

chemical

and

biological

hazards.

The

following

are

examples:

Chemicals,

plant

and

animal

substances

in

those

teaching

the

sciences,

wood

dusts,

metal

fumes,

glues

and

noise

in

teachers

of

technical

subjects,

physical

violence

from

pupils

or

parents,

communicable

diseases,

ergonomic

problems

associated

with

bending,

manual

handling

and

sitting

on

small

chairs,

trauma

for

those

involved

in

teaching

physical

education

and

any

extra-curricular

activities

and

voice

trauma

[14].

Physical

Health

Only

a

few

studies

of

varying

quality

have

been

published

on

teachers'

physical

health.

When

considering

the

main

classes

of

diagnoses

of

physical

diseases;

musculoskeletal,

respiratory,

cardiovascular,

nervous

and

hormonal

disorders

[14].

Moreover,

when

focusing

on

cardiovascular

disorders,

a

study

carried

out

in

Germany

showed

that

there

was

a

lower

risk

for

male

teachers

compared

to

men

working

in

12

other

professions

[15].

Another

study

at

KSA

during

1995

found

the

prevalence

of

obesity

in

males

as

46%

and

females

49%

[16].

About

12%

of

all

teachers

were

considered

hypertensive,

18%

of

males

and

2%

of

females

were

current

cigarette

smokers.

A

greater

proportion

of

males

(57%)

than

females

(20%)

indicated

they

were

performing

a

physical

exercise

at

least

one

hour

per

week,

13%

of

males

and

11%

of

females

had

hypercholesterolemia.

Hypertriglyceridemia

was

found

in

12%

of

males

and

4%

of

females,

and

hyperglycemia

was

found

in

8%

of

males

and

4%

of

females.

Conclusions:

The

prevalence

of

cardiovascular

risk

factors

among

school

teachers

is

not

much

different

to

that

found

in

developed

countries

[16].

A

study

at

KSA

during

2006/2007

found

the

prevalence

of

hypertension

(HTN)

and

pre-hypertension

was

25.2

%

in

males

and

43.0

%

in

females

and

diabetes

was

significantly

associated

with

HTN

[17].

A

study

conducted

in

Sofia

,

Bulgaria

(1994),

found

that

the

estimated

relative

risk

of

arterial

HTN

for

female

teachers

was

1.5

compared

with

other

female

employees

(designers,

researchers)

who

served

as

controls.

This

finding

can

classify

the

teaching

occupation

as

high

risk

for

arterial

hypertension

[18].

MSD

represents

one

of

the

most

common

and

most

expensive

occupational

health

problems

in

both

developed

and

non-developing

countries

[19].

MSD

is

one

of

the

leading

causes

for

ill

health

retirement

among

school

teachers

[20].

Musculoskeletal

complaints,

especially

of

the

lower

back,

neck

and

shoulders

are

also

common

among

teachers.

Recently,

Hong

Kong

teachers

showed

a

higher

prevalence

for

neck

(68.9%),

shoulder

(73.4%)

and

low

back

pain

(59.2%)

in

the

past

30

days

[21].

Epidemiological

studies

have

demonstrated

that

factors

such

as

gender,

age,

length

of

employment

and

awkward

posture

are

associated

with

higher

MSD

prevalence

among

teachers

[19].

Among

workers

including

teachers,

prolonged

posture,

static

work

and

repetition

are

the

cause

of

repetitive

strain

injuries

(RSIs),

which

is

one

type

of

MSD

that

directly

affects

the

area

of

upper

limb,

neck,

shoulder

and

low

back

[22].

Smith

et

al.,

1997

showed

that

compared

to

a

control

group,

teachers

were

significantly

more

likely

to

report

having

6

voice

symptoms,

among

which

hoarseness

was

the

most

frequent,

and

5

related

physical

discomfort

symptoms

(tiring,

effortful,

ache,

uncomfortable

and

rough)

[23,24].

It

is

worth

mentioning

that

there

are

a

few

additional

studies

that

have

shown

a

different

impact

of

a

few

other

diseases

on

teachers:

an

excessive

rate

of

some

major

cancers,

in

particular

breast

[25]

and

thyroid

[26]

cancers

and

surprisingly

enough,

an

association

between

school

teaching

and

mortality

from

autoimmune

diseases

[27].

A

study

by

Kovess-Masféty,

said

that

teachers

do

not

seem

to

have

poorer

mental

health.

However,

their

physical

condition

is

characterized

by

a

higher

prevalence

of

health

problems

related

to

the

ENT

tract,

and

to

a

lesser

extent,

depending

on

the

gender,

to

skin,

eyes,

legs

and

lower

urinary

tract

[28].

Teachers

have

an

important

responsibility

in

tobacco

control

given

that

they

are

highly

respected

in

their

communities

as

they

influence

the

evolution

for

each

aspect

of

life

[29].

In

addition,

teachers

have

daily

interaction

with

students

and

thus

represent

an

influential

group

in

tobacco

smoking

control.

However,

this

potential

can

be

limited

if

teachers

use

tobacco

especially

in

the

presence

of

students

in

school

premises

[30].

Psychological

Teaching,

like

many

jobs,

is

potentially

stressful.

Some

sources

of

pressure

are

specific

to

teaching

but

others

are

common

to

various

professions

and

management

structures.

Pressures

which

teachers

have

encountered

include:

the

need

to

be

continually

vigilant

when

supervising

pupils,

verbal

abuse

from

pupils

and

parents,

parental

expectations,

the

requirement

to

manage

staff

including

support

assistants

and

other

teachers,

the

responsibility

for

head

teachers

to

effectively

manage

a

'business',

pressure

from

peers

and

colleagues,

coping

with

change

e.g.

in

management

systems,

examination

formats

and

the

curriculum

and

poor

or

inappropriate

management

including

delays

in

addressing

disciplinary

and

grievance

issues

[14].

Factors

Affecting

Teachers'

Mental

Health

These

include

the

lack

of

professional

aptitude

and

spirit,

occupational

hazards,

lack

of

social

prestige,

poor

salaries,

high

moral

expectations,

workload,

relationship

among

teachers,

relationship

between

the

administrator

and

teachers,

insecurity

of

service

and

lack

of

facilities

[14].

Study

design

Cross

sectional

research

design

Population

and

sampling

Male

teachers

in

Abha

City

constitute

the

study

population.

The

minimum

sample

size

for

this

study

has

been

decided

according

to

Swanson

and

Cohen

[31].

Following

a

simple

random

sample,

the

researcher

selected

an

equal

sample

from

primary,

intermediate

and

secondary

school

male

teachers

in

Abha

City.

All

respondent

teachers

were

exposed

to

the

questionnaire.

According

to

the

Ministry

of

Education

in

Aseer

region

data,

the

number

of

schools

in

Abha

city

are

96

schools

divided

into

46

primary,

33

intermediate

and

17

secondary

with

2219

teachers

in

all

levels.

So

the

average

number

in

each

school

is

about

23

teachers.

Number

of

teachers

in

primary

schools

was

1063,

intermediate

schools

was

763

and

secondary

schools

was

393

teachers.

Proportionate

sample

was

taken

from

each

level

according

to

the

following

formulas:

Primary=

384

(Sample

Size)

X

1063/

2219=184;

Intermediate=

384

(Sample

Size)

X

763/

2219

=132;

Secondary

=

384

(Sample

Size)

X

393/

2219=

68

So

in

Primary

level

we

selected

184

teachers

from

8

male

Schools

[due

to

socio-cultural

aspect]

randomly

from

the

total

primary

schools

to

cover

their

sample

size

and

avoided

non

responders

and

6

intermediate

schools

and

3

secondary

schools.

We

asked

all

school

teachers

to

participate

in

the

research.

If

extra

numbers

will

be

needed,

extra

schools

will

be

selected

randomly

soon.

Data

Collecting

Tool

Sample

of

Employment

Health

Questionnaire

(Department

of

Health)

[32].

Data

Design

A

self-administered

questionnaire

including

Personal

characteristics

as

Demographic

data,

medical

history

and

co-morbidities

and

Special

Habits,

was

designed.

Administrative

consideration:

The

Researcher

fulfilled

all

the

required

official

approvals.

The

researcher

explained

to

all

participants

how

to

fill

out

the

questionnaire

in

the

correct

way

and

how

to

answer

questions.

Ethical

consideration:

Before

Interviewing,

Informed

Consent

was

asked

from

all

samples

then

all

participants

had

the

right

not

to

participate

in

the

study

or

to

withdraw

from

the

study

prior

to

completion.

The

researcher

explained

the

purpose

to

all

respondents.

This

pre

measurement

education

is

an

important

part.

Confidentiality

and

privacy

were

guaranteed

for

all

participants.

Budget

This

study

was

carried

out

at

the

full

expense

of

the

researchers.

Statistical

Analysis

The

statistical

analysis

of

data

was

done

by

using

Excel

program

for

figures

and

SPSS

(SPSS,

Inc,

Chicago,

IL)

program

statistical

package

for

social

science

version

17

[33].

The

description

of

the

data

was

done

in

form

of

mean

(+/-)

SD

for

quantitative

data

and

Frequency

and

proportion

for

Qualitative

data.

The

analysis

of

the

data

was

done

to

test

statistical

significant

difference

between

the

groups.

For

quantitative

date,

student

t-test

was

used

to

compare

between

two

groups.

Chi

square

test

was

used

for

qualitative

data

and

odds

ratio

for

risk

assessment.

Pearson

Correlation

was

done

to

detect

association

between

variables.

P

is

significant

if

<

0.05

at

confidence

interval

95%.

In

socio-demographic

data

of

male

teachers

in

Abha

City

(N=384)

we

found

the

mean

age

of

39.31,

Gender

(male)

384

(100%),

experience

less

than

or

equal

to

10

years

was

109

(28.4%),

experience

more

than

or

equal

to

10

years

was

275

(71.6%)

and

level

of

schools:

primary

(47.9

%),

intermediate

(34.4

%)

and

secondary

(17.7%)

.

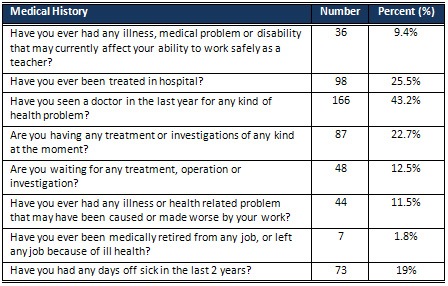

Table

1:

Medical

history

of

male

teachers

in

Abha

City

2014

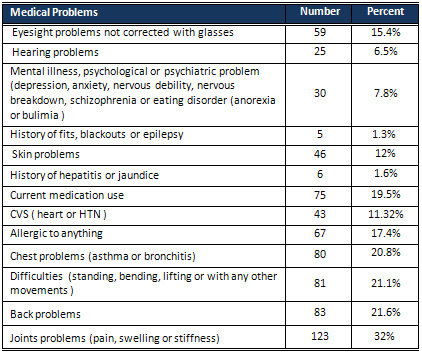

Table

2:

Medical

Problems

of

male

teachers

in

Abha

City

2014

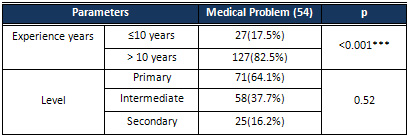

Table

3:

Relation

between

medical

problem

and

experience

years

and

level

of

male

teachers

This

study

was

done

to

assess

the

health

aspect

of

male

teachers

(384)

and

to

assess

level

of

job

satisfaction

of

male

teachers

in

different

grades

in

Abha

city.

A

simple

random

sample,

the

sample

from

primary,

intermediate

and

secondary

school's

male

teachers

in

Abha

City,

was

selected.

All

respondent

teachers

were

exposed

to

the

validated

questionnaire

to

assess

health

problem

[medical

history

and

co-morbidities]

and

work

place

risk

factors.

In

our

study

background

data

is

shown

as

age

39.31±7.96

[23:75]

years,

the

average

experience

years

were

16.1±7.43

[1:36]

years

and

71.6%

have

experience

more

than

10

years,

100

%

of

the

sample

was

males

due

to

socio-cultural

matters.

As

regards

the

educational

level

47.9%

were

from

primary

schools,

34.4%

from

intermediate

schools

and

17.7%

from

secondary

schools.

The

answers

about

some

medical

history

like

history

of

having

medical

problem

that

affects

teacher'

ability

(9.4%),

history

of

treating

in

hospital

(25.5%)

,

sick

leave

19%

are

all

within

the

accepted

range

but

seeing

a

doctor

in

last

year

(43.2%)

seems

to

be

higher

than

normal

range

and

mostly

due

to

respiratory

infections.

Kovess-Masféty,

V.,

et

al

2009

[28]

reported

in

France

that

among

teachers

their

physical

condition

is

characterized

by

a

higher

prevalence

of

health

problems.

Some

complaints

or

health

problems

among

teachers

in

our

study

regarding

eyesight

problems

recorded

(15.4%).

This

is

lower

than

Chong,

E.

Y.,

&

Chan,

A.

H.

(2010)

in

Hong

Kong

who

reported

32%

to

43%

eye

problems

among

teachers

[21].

Hearing

problems

in

6.5%;

this

is

lower

than

Martins,

R.

H.

G.

Et

al.,

2007

who

reported

25%

compared

to

10%

in

controls

with

an

acoustic

notch

predominating

(11.25%;

p<0.05),

due

to

excessive

classroom

noise

(93.5%)

and

auditory

symptoms

(65%).

Noise

levels

close

to

87dBA

were

recorded

in

classes

at

all

teaching

levels

[34].

Mental

illness,

psychological

or

psychiatric

problem,

including

depression,

anxiety,

nervous

debility,

nervous

breakdown,

schizophrenia

or

eating

disorder

was

7.8%

and

is

much

lower

than

Chong,

E.

Y.,

&

Chan,

A.

H.

(2010)

in

Hong

Kong

who

reported

high

prevalence

of

Pseudo-neurological

and

mental

disorders

among

teachers.

The

lower

rates

in

this

study

may

be

due

to

fear

of

social

stigma

in

our

society

and

under-estimation

and

ignorance

about

the

nature

of

psychological

diseases

[21].

The

skin

problems

(12%)

may

be

due

to

exposure

to

various

irritants,

either

chemical

or

biological

factors

in

schools.

This

is

lower

than

Chong,

E.

Y.,

&

Chan,

A.

H.

(2010)

who

reported

skin

problems

among

teachers

in

Hong

Kong

at

24.4%

[21].

The

history

of

hepatitis

or

jaundice

1.6%

is

much

less

than

prevalence

of

all

types

of

hepatitis

especially

in

the

southwestern

area

of

KSA

as

detected

by

Abdo,

A.

A.,

2012.

This

may

explained

by

health

appraisal

and

screening

being

done

before

job

allocation

[36].

The

heart

or

blood

pressure

problems

were

11.32%

and

this

rate

is

lower

than

community

prevalence

and

does

not

differ

than

the

level

in

developed

countries

as

detected

by

Ghabrah,

T.

M

et

al.,1998,

[16]

but

is

not

in

agreement

with

Ibrahim,

N.

K

et

al.,

2008

in

his

study

in

Jeddah

which

was

higher.

This

difference

may

come

from

the

detected

prevalence

of

risk

factors

like

obesity

which

was

lower

in

our

area

[17].

The

history

of

allergy

was

17.4%

due

to

exposure

to

different

chemical

and

biological

irritants

in

the

school

environment;

this

is

in

agreement

with

Chong,

E.

Y.,

&

Chan,

A.

H.

(2010).

A

study

in

Hong

Kong

reported

19%

prevalence

of

allergy

among

school

teachers

[21].

Suffering

from

asthma

or

chest

problem

was

reported

in

20.8%

due

to

drawbacks

from

allergy

or

recurrent

chest

infections.

This

is

higher

than

Chong,

E.

Y.,

&

Chan,

A.

H.

(2010)

[21]

in

Hong

Kong

who

reported

16.1%.

The

difference

could

be

explained

by

Al

Frayh,

A.

R.,

et

al.,

2001

[37]

who

reported

data

between

Riyadh

versus

Hail

(inland

desert

dry

environment)

and

Jeddah

versus

Gizan

(coastal

humid

environment)

which

revealed

that

the

prevalence

of

asthma

in

the

similar

populations

increased

significantly

from

8%

in

1986

to

23%

in

1995

due

to

environmental

changes.

History

of

Musculoskeletal

disorder

21.1%,

Low

back

pain

21.6%

and

joint

pain

32%.

These

high

rates

due

to

age,

length

of

employment

and

awkward

posture,

prolonged

posture,

static

works

and

repetition

are

the

cause

of

repetitive

strain

injuries

which

are

associated

with

higher

MSD

prevalence

rates

among

teachers.

This

is

matched

with

Erick

PN,

Smith

DR,2011

who

reported

that

the

schoolteachers

represent

an

occupational

group

among

which

there

appears

to

be

a

high

prevalence

of

MSD

[19].

In

our

study,

regarding

the

relation

between

medical

problem

and

experience

years

and

level

among

the

studied

Group

there

is

a

significant

association

between

medical

problem

and

experience

years

more

than

10

years

due

to

accumulation

of

stressors

and

chronic

diseases

so

the

effect

may

be

a

false

association

due

to

confounder

effect

of

the

aging

process.

There

was

no

significant

association

with

specific

educational

level;

this

may

explained

by

the

same

stressors

present

in

all

levels.

The

medical

problems

of

male

teachers

increase

with

age

increase.

The

health

status

of

male

teachers

is

not

optimal

since

a

high

percentage

of

them

have

to

see

a

doctor

each

year

and

one

third

of

them

are

currently

sick.

Moreover,

musculoskeletal

problems

are

quite

common

among

male

teachers.

Provision

of

health

educational

program

about

the

risks

which

the

teachers

have

been

exposed

to,

either

communicable

or

non-communicable.

Establishment

of

a

specific

health

program

for

teachers

caring

with

their

health

status.

More

availability

of

preventive

health

care

measures

to

avoid

co-

morbidities

associated

with

work

environment.

Multidisciplinary

team

approach

toward

the

screening

and

diagnosis

of

health

hazards

among

teachers

that

consists

of

"Clinical,

Laboratory,

radiological,

Occupational

and

epidemiological

researcher

teams".

1.

Smylie

MA.

Teacher

stress

in

a

time

of

reform.

In

R.

Vandenberghe

&

AM.

Huberman

(Eds.),

Understanding

and

preventing

teacher

burnout

(pp.

59-84).

Cambridge:

Cambridge

University

Press,

1999.

2.

Ewing

RA,

Smith

DL.

Retaining

quality

beginning

teachers

in

the

profession.

English

Teaching:

Practice

and

Critique,

2003;

2(1):

15-32.

3.

Ramsey

G.

Quality

matters.

Revitalising

teaching:

Critical

times,

critical

choices.

Sydney:

New

South

Wales

Department

of

Education

and

Training.

2000,

Retrieved

10

August

2004,

from

http://www.det.nsw.edu.au/teachrev/reports/

4.

Macdonald

D.

Teacher

attrition:

a

review

of

literature.

Teaching

and

Teacher

Education,

1999;

15:

835-848.

5.

Nelson

B.

Our

universities:

Backing

Australia's

future.

Certo,

J.L.,

&

Fox,

J.E.

(2002).

Retaining

quality

teachers.

The

High

School

Journal,

2003;

86(1):

57-

75.

6.

Dunn

D.

Teaching

about

the

good

life:

Culture

and

subjective

well-being.

Journal

of

Social

and

Clinical

Psychology,

2002;

21(2),

218-220.

7.

Brouwers

A,

Tomic

W.

A

longitudinal

study

of

teacher

burnout

and

perceived

self-

efficacy

in

classroom

management.

Teaching

and

Teacher

Education,

2000;

16:

239-253.

8.

Smith

M,

Bourke

S.

Teacher

stress:

Examining

a

model

based

on

context,

workload,

and

satisfaction.

Teaching

and

Teacher

Education,

1992;

8(1):

31-46.

9.

Singh

K,

Billingsley

BS.

Intent

to

stay

in

teaching.

Remedial

&

Special

Education,

1996;

17(1):

37-48.

10.

The

Management

of

Health

and

Safety

at

Work

Regulations

1999.

11.

Desjean-Perrotta

B.

Developing

a

fitness

to

teach

policy

to

address

retention

issues

in

teacher

education.

Childhood

Education,

2006;

83(1):

23-28.

12.

Alzaidi

AM.

A

Qualitative

Study

of

Job

Satisfaction

among

Secondary

School

Head

Teachers

in

the

City

of

Jeddah,

Saudi

Arabia.

ARECLS,

2008;

4:

1-15.

13.

Chance

P.

That

burned

out,

used-up

feeling

Psychology

Today.

Prentice

Hall,

New

Delhi.1981.

14.

Seibt,

R,

Lützkendorf

L,

Thinschmidt

M.

Risk

factors

and

resources

of

work

ability

in

teachers

and

office

workers.

In

International

Congress

Series.

Elsevier,

2005;

1280:

310-315.

15.

Helmert

U,

Shea

S,

Bammann

K.

The

impact

of

occupation

on

self-reported

cardiovascular

morbidity

in

western

Germany:

gender

differences.

Reviews

on

environmental

health,

1997;

12(1):

25-42.

16.

Ghabrah

T

M.,

Bahnassy,

A

A.,

Abalkhail

B

A,

Soliman

NK.,

Milaat,

WA.

The

prevalence

of

cardiovascular

risk

factors

among

school

teachers

in

Jeddah,

Saudi

Arabia.

Journal

of

the

Saudi

Heart

Association,

1998;

10(3):

189-195.

17.

Ibrahim

NK,

Hijazi

NA,

Al-Bar

AA.

Prevalence

and

determinants

of

prehypertension

and

hypertension

among

preparatory

and

secondary

school

teachers

in

Jeddah.

J

Egypt

Public

Health

Assoc,

2008;

83(3-4):183-203.

18.

Deyanov

C,

Hadjiolova

I,

Mincheva

L.

Prevalence

of

arterial

hypertension

among

school

teachers

in

Sofia.

Reviews

on

environmental

health,

1994;

10(1):

47-50.

19.

Erick

PN,

Smith

DR.

A

systematic

review

of

musculoskeletal

disorders

among

school

teachers.

BMC

musculoskeletal

disorders,

2011;

12(1):

260.

20.

Maguire

M,

O'Connell

T.

Ill-health

retirement

of

schoolteachers

in

the

Republic

of

Ireland.

Occupational

Medicine,

2007;

57(3):

191-193.

21.

Chong

EY,

Chan

AH.

Subjective

health

complaints

of

teachers

from

primary

and

secondary

schools

in

Hong

Kong.

International

journal

of

occupational

safety

and

ergonomics,

2010;

16(1):

23-39.

22.

Chaiklieng

S,

Suggaravetsiri

P.

Risk

factors

for

repetitive

strain

injuries

among

school

teachers

in

Thailand.

Work:

A

Journal

of

Prevention,

Assessment

and

Rehabilitation,

2012;

41:

2510-2515.

23.

Titze

IR,

Lemke

J,

Montequin

D.

Populations

in

the

US

workforce

who

rely

on

voice

as

a

primary

tool

of

trade:

a

preliminary

report.

Journal

of

Voice,

1997;

11(3):

254-259.

24.

Williams

NR.

Occupational

groups

at

risk

of

voice

disorders:

a

review

of

the

literature.

Occupational

medicine,

2003;

53(7):

456-460.

25.

Bernstein

L,

Allen

M,

Anton-Culver

H,

Deapen

D,

Horn-Ross

PL,

Peel

D

et

al.

High

breast

cancer

incidence

rates

among

California

teachers:

results

from

the

California

Teachers

Study

(United

States).Cancer

Causes

&

Control,

2002;

13(7):

625-635.

26.

Lope

V,

Pollán

M,

Gustavsson

P,

Plato

N,

Pérez-Gómez

B,

Aragonés

N,

López-Abente

G.

Occupation

and

thyroid

cancer

risk

in

Sweden.

Journal

of

occupational

and

environmental

medicine,

2005;

47(9):

948-957.

27.

Walsh

SJ,

DeChello

LM.

Excess

autoimmune

disease

mortality

among

school

teachers.

The

Journal

of

rheumatology,2001;

28(7):

1537-1545.

28.

Kovess-Masféty

V,

Sevilla-Dedieu

C,

Rios-Seidel

C,

Nerrière

E,

Chee

CC.

Do

teachers

have

more

health

problems?

Results

from

a

French

cross-sectional

survey.

BMC

Public

Health,

2006;

6(1):

101.

29.

Al-Naggar

RA,

Jawad

AA,

&Bobryshev

YV.

Prevalence

of

cigarette

smoking

and

associated

factors

among

secondary

school

teachers

in

Malaysia.

Asian

Pacific

J

Cancer

Prev,

2012;

13:

5539-5543.

30.

GTSS

Collaborative

Group.

The

Global

School

Personnel

Survey:

a

cross?country

overview.

Tobacco

Control,

2006;

15(Suppl

2),

ii20.

31.

Swanson

Cohen

JM.

Color

vision.

Ophthalmol

Clin

North

Am.

2003;

16(2):179-203.

32.

Department

of

Health,

Department

for

Education

and

Employment,

Public

Health

Laboratory

Service

1999

.

33.

SPSS

Inc..

Statistical

Package

for

the

Social

Sciences,

17.

Chicago,

Illinois:

SPSS

Inc.

2008.

34.

MartinsRHG,

Tavares

ELM,

Lima

Neto

AC,

Fioravanti

MP.

Occupational

hearing

loss

in

teachers:

a

probable

diagnosis.

Revista

Brasileira

de

Otorrinolaringologia,

2007;

73(2):

239-244.

35.

Al

Rajeh

S,

Awada

A.

Stroke

in

Saudi

Arabia.

Cerebrovascular

Diseases,

2002;

13(1):

3-8.

36.

Abdo

AA,

Sanai

FM,

Al-Faleh

FZ.

Epidemiology

of

viral

hepatitis

in

Saudi

Arabia:

Are

we

off

the

hook?.

Saudi

journal

of

gastroenterology:

official

journal

of

the

Saudi

Gastroenterology

Association,2012;

18(6):

349.

37.

Al

Frayh

AR,

Shakoor

Z,

ElRab

MO,

Hasnain

SM.

Increased

prevalence

of

asthma

in

Saudi

Arabia.

Annals

of

Allergy,

Asthma

&

Immunology,

2001;

86(3):

292-296.

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|