|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor) |

|

|

|

|

........................................................

|

Original

Contribution/Clinical Investigation

|

|

|

<-- Turkey -->

Preoperative

management of sickle cell patients with hydroxyurea

[pdf version]

Mehmet Rami Helvaci,

Sedat Hakimoglu, Mehmet Oktay Sariosmanoglu,

Suleyman Kardas, Beray Bahar, Merve Filoglu,

Ibrahim Ugur Deler, Duygu Alime Almali, Ozcan

Gokpinar, Ozlem Celik, Aynur Ozbay, Ozgun Ilke

Karagoz, Seher Aydin

<-- Ethiopia-->

Khat

(Catha edulis) chewing as a risk factor of low

birth weight among full term Newborns: A systematic

review

[pdf version]

Kalkidan Hassen

<-- Australia -->

Chronic

pain review following Lichtenstein hernia repair:

A Personal Series

[pdf

version]

Maurice Brygel,

Luke Bonato, Sam Farah

<-- Saudi Arabia -->

Assessment

of Health Status of Male Teachers in Abha City,

Saudi Arabia

[pdf

version]

Ali Mofareh Assiri,

Hassan M. A. Al-Musa

|

|

........................................................ |

Evidence

Based Medicine

........................................................

Medicine and Society

........................................................

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| October 2015 -

Volume 13 Issue 7 |

|

|

Chronic pain review following

Lichtenstein hernia repair:

A Personal Series

Maurice

Brygel (1)

Luke Bonato (2)

Sam Farah (3)

(1) Mr Maurice Brygel MBBS FRACS General Surgeon,

Director Melbourne Hernia Clinic, Masada hospital,

Melbourne Victoria,

Australia

(2) Dr Luke J Bonato MBBS

Surgical HMO,

Melbourne Victoria,

Australia

(3) Dr Sam S Farah, MBBS(Hons)

Master of Medicine (Clinical Epidemiology)

Student Intern, Southern Health, Melbourne

Victoria,

Australia

Correspondence:

Mr Maurice Brygel 26 Balaclava Road East St

Kilda Vic 3183

Australia

Ph: +61 3 9525 9077

Fax: +61 3 9527 1519

Email: mbrygel@netspace.net.au

|

Abstract

Introduction:

Chronic groin pain is both a topical subject

and important outcome measurement following

inguinal hernia repair. It has been suggested

its incidence is related to the management

of the nerves of the inguinal canal as

well as the type of mesh used and methods

of fixation for both open and laparoscopic

surgery.

The level of pre-operative

and post operative pain, its duration

as well as complications may all be factors

in predicting whether chronic pain may

develop. The method of measurement of

chronic pain is itself a contentious issue.

It is now apparent that the measurement

of activity and functional status as well

as qualitative measures is important.

Uniform methods

of assessing chronic post-operative pain

have been proposed.

Methods:

A retrospective study reviewing a consecutive

series of Lichtenstein repairs performed

by a single experienced hernia surgeon

was carried out. 248 inguinal hernia patients

operated on in 2005 were reviewed. Patients

were contacted via telephone at a median

of 50 months. A recently validated inguinal

pain questionnaire was used to assess

the incidence of chronic pain.

Results: 185

(75%) patients were able to be contacted

for follow-up, making a total of 213 inguinal

hernia repairs (including bilateral hernias).

At the time of review 3% of patients reported

having pain. No patients reported that

pain or discomfort was limiting their

work, exercise or activities of daily

living. No patients had disabling pain.

Conclusion:

Chronic pain did not appear to be a major

problem within this cohort of patients.

The Lichtenstein technique can produce

favourable results in terms of chronic

pain for unilateral, bilateral and recurrent

inguinal hernias in an unselected group

of patients with the usual mix of risk

factors and complications.

Key words:

Inguinal hernia, Lichtenstein, Local anaesthesia,

Chronic pain, Bilateral inguinal hernia,

Recurrent inguinal hernia

Abstract presentation

delivered to:

The Royal Australasian College Of Surgeons

Annual Scientific Congress, Perth, May

2010.

The American Hernia Society, Hernia Repair

Conference 2010, Orlando, Florida, March

2010.

|

Inguinal hernia repairs are one of the most

common surgical procedures(1). The pre-eminent

status of the original Lichtenstein technique

has been challenged with the introduction of

other open and laparoscopic techniques, lightweight

meshes and new methods of fixation with absorbable

tackers and tissue glues. While there has been

significant improvement in recurrence rates

with most types of mesh repair(2), a variable

and worrying incidence of chronic pain following

open and laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias

has been documented(3).

There is still controversy regarding the true

incidence of chronic pain. The lack of uniform

definitions and interpretation as well as different

methods of assessment has lead to this(4-6).

Mild, moderate and severe pain has been reported

to have a prevalence of 0.7% to 43.3%(3), with

some treating the presence of pain as a dichotomous

(yes/no) entity.(7) An overall prevalence of

0.5 - 6% of severe debilitating pain affecting

normal daily activities and work has been reported(3).

It has also been suggested that the rates of

severe chronic pain are lower with laparoscopic

repair, compared with Lichtenstein repair or

other open techniques, as well as being associated

with earlier return to work and normal activities(8).

This however is associated with more adverse

events during surgery(9) as well as higher rates

of visceral injury(10).

Other factors such as patient profile, the

level of pre-operative pain, type of hernia,

post-operative pain and complications are also

being assessed as to their significance in assessing

the risk of the development of chronic pain(8).

Many methods including numerical and behavioural

rating scales have been used to assess the levels

of chronic pain(11), attesting to the difficulty

in assessment and interpretation. Standardization

of methods of measuring results is required(7).

Franneby's(11) validated chronic inguinal pain

questionnaire (IPQ) was used in this study.

This was chosen because of the comprehensive

but simple nature of the questionnaire. This

also incorporated pain behavior rather than

numbers. The IPQ also addressed many of the

issues surrounding this difficult concept, and

went a great way towards providing accurate

assessment.

Many of the multicentre trials used in larger

systematic reviews(10) that govern current guidelines(12)

incorporate many different surgeons of varying

levels of experience(9). To gain further insight

a consecutive series of patients operated on

using the Tension Free Lichtenstein Technique

(TFLT) with local anaesthesia and standard mesh

in 2005 by a single experienced hernia surgeon

were reviewed.

The primary objective of this study was to

assess the incidence of chronic pain, using

a validated inguinal pain questionnaire(11).

This series aims to address the issues previously

raised when investigating the incidence of chronic

pain(13), in particuar inadequate analysis.

The Lichtenstein technique(14) was used in a

consecutive series of patients with unilateral,

bilateral and recurrent inguinal hernias.

Approval

was

obtained

from

The

Avenue

Hospital

Human

Research

Ethics

Committee,

Ramsay

Health,

Melbourne,

Australia.

Patients

Selection

&

Baseline

Data

All

patients

who

underwent

a

primary

inguinal

hernia,

bilateral

inguinal

hernia,

or

recurrent

inguinal

hernia

repair

in

2005

were

included.

Patients

were

then

contacted

in

2009,

at

a

median

of

50

months

post-operatively

by

one

of

the

research

team.

The

follow-up

rate

was

75

%.

An

extensive

interview

based

on

Franneby's

IPQ(11)

was

conducted.

A

review

of

the

patient's

medical

records,

together

with

audit

forms

completed

at

the

time

of

operation

was

undertaken.

The

level

of

pre-operative

pain,

co-morbidities

and

type

and

size

of

the

hernia

had

been

recorded

pre-operatively.

The

method

of

repair,

mesh

and

fixation

used,

together

with

the

management

of

the

nerves

was

documented.

The

post-operative

complications,

post-operative

pain,

analgesic

requirements,

patient's

interpretation

of

the

pain,

and

return

to

normal

activities

and

work

had

been

documented

during

the

routine

post-operative

visits.

The

level

of

analgesics

required

post-operatively

and

return

to

normal

activities

was

reviewed.

Inguinal

Pain

Questionnaire

(IPQ)

The

IPQ

uniquely

explored

pain

intensity

rather

than

its

presence

or

absence.

This

allowed

for

a

more

meaningful

examination

of

pain,

and

pain

behavior.

The

IPQ

measured

•

Pain

and

its

impact

on

daily

activities

was

examined

across

four

different

periods:

preoperatively,

post-operatively,

time

of

interview,

and

the

week

preceding

the

interview,

using

the

following

scale;

i.

No

Pain

ii.

Pain

present

but

can

easily

be

ignored

iii.

Pain

present,

cannot

be

ignored,

but

does

not

interfere

with

everyday

activities

iv.

Pain

present,

cannot

be

ignored,

interferes

with

concentration

on

chores

and

daily

activities

v.

Pain

present,

cannot

be

ignored,

interferes

with

most

activities

vi.

Pain

present,

cannot

be

ignored,

necessitates

bed

rest

vii.

Pain

present,

cannot

be

ignored,

prompt

medical

advice

sought

•

When

pain

ceased.

•

How

often

had

the

participant

felt

pain

in

the

operate

groin

during

the

past

week,

and

how

long

they

may

have

lasted.

•

Current

analgesia

requirements.

•

Activities

of

daily

life

associated

questions.

•

Any

work

limitations.

The

Lichtenstein

Technique(14)

Anaesthesia

All

repairs

were

carried

out

using

Local

Anaesthetic

(LA)

infiltration

and

light

intravenous

sedation,

including

Fentanyl,

Propofol

or

Midazolam

and

anti-inflammatory

agents.

The

combination

used

depended

largely

on

the

anaesthetist's

preference.

A

mixture

of

Lignocaine

2%

with

Adrenaline

1:

200,000

and

plain

Bupivacaine

0.5%

were

used.

LA

was

directly

infiltrated

into

the

skin

and

subcutaneous

tissues

after

an

initial

dose

of

sedation.

The

sedation

avoided

the

possible

discomfort

of

the

injections.

The

ilioinguinal

nerve(IIN)

and

the

iliohypogatric

nerves

(IHN)

were

blocked

by

introducing

the

LA

deep

to

the

external

oblique

aponeurosis

under

direct

vision.

This

gave

rapid

anaesthesia

and

displaced

the

IIN

and

IHN

from

the

external

oblique

making

direct

injury

to

the

nerves

and

their

perineurium

less

likely.

The

LA

helped

identify

and

dissect

the

tissue

planes

as

it

was

injected

around

the

hernial

sac

and

cord

and

into

the

region

of

the

genital

division

of

the

GFN.

A

formal

ilio-inguinal

nerve

(IIN)

block

at

the

anterior

superior

iliac

spine

was

not

performed,

as

in

the

surgeon's

experience

patients

frequently

complained

of

post-operative

pain

at

the

site

of

injection.

Moreover,

this

technique

takes

longer

to

become

effective

and

adds

to

the

overall

volume

of

LA

required.

The

Nerves

The

identification

and

management

of

the

nerves

was

recorded.

An

attempt

was

made

to

identify

all

3

nerves.

However

an

extensive

search

was

not

carried

out

as

this

could

increase

tissue

trauma

and

possibly

damage

the

nerves.

In

the

majority

of

cases,

all

nerves

were

identified

and

spared.

If

the

nerve

had

been

traumatised

or

was

compromised

by

the

mesh

or

suturing,

it

was

dissected

back

to

the

muscle,

divided

and

removed

totally,

(neurectomy).

Diathermy

or

ligation

of

the

stump

was

not

employed.

The

IIN

was

usually

not

separated

from

the

cord.

Care

was

taken

in

closing

the

external

oblique

to

avoid

entrapping

the

IIN.

Surgical

technique:

The

Lichtenstein

technique

has

been

well

described(14).

Some

important

aspects

of

the

technique

and

possible

differences

include:

•

No

diathermy

was

used;

it

is

believed

this

could

cause

tissue

and

nerve

damage

setting

up

a

neuropathic

and

nocioceptive

inflammatory

response.

•

Adrenaline

kept

the

blood

loss

to

a

minimum.

•

Sharp

dissection

was

used

to

reduce

trauma.

•

The

Local

Anaesthetic

technique

requires

a

gentler

dissection.

•

For

indirect

hernias

the

sac

was

either

excised

or

reduced

(especially

for

sliding

hernias).

•

For

direct

hernias

the

sac

was

reduced.

•

Any

additional

lipoma

of

the

cord

was

always

excised.

•

A

standard

Polypropylene

mesh

was

used

Prolene

(trademark)

mesh,

Polypropylene,

non-absorbable

synthetic

surgical

mesh,

Johnson

&

Johnson.

•

A

standard

skin

stapler

(Appose

35w

auto

suture)

was

used

to

fix

the

mesh

to

the

inguinal

ligament

as

per

the

Lichtenstein

technique.

The

mesh

was

placed

well

medial

to

pubic

tubercle,

but

the

staples

were

placed

well

away

from

the

pubic

tubercle.

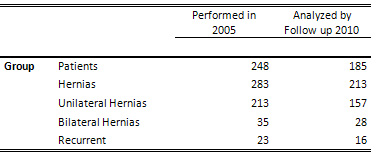

A

total

of

248

patients

were

operated

on

in

2005.

This

equated

to

283

hernias

including

35

bilateral,

and

23

recurrences.

185

patients

were

contacted

in

2010.

This

equated

to

213

hernia

repairs

with

28

bilateral

and

16

recurrences

equating

to

a

follow-up

rate

of

75%

(Table

1).

Table

1:

Number

of

Patients,

and

distribution

of

hernia

subtypes

Patient

demographics

(of

original

cohort)

Age

distribution

was

between

18

-

90

years.

The

majority

between

50

-

60

years

of

age

n

=

73

(28.85%).

241

(97%)

of

the

patients

were

male,

and

7

(3%)

were

female.

Inguinal

Pain

Questionnaire

(IPQ)

67%

(n

=

124)

of

patients

reported

pre

operative

pain.

This

ranged

in

severity

between

pain

that

could

be

easily

ignored

(27%)

to

pain

which

required

hospitalization

(3%).

33%

(n

=

61)

of

patients

reported

no

pain

at

all.

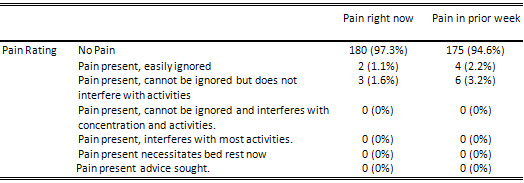

Table

2:

Comparison

of

pain

ratings

The

proportion

of

patients

with

pain

at

time

of

interview

was

3%

(95%

CI:

1%

to

5%,

P<0.001)

(Table

2).

Of

those

who

reported

pain:

•

1.1%

(n

=

2)

reported

that

their

pain

did

not

interfere

with

their

normal

activities

and

could

be

easily

ignored.

•

1.6%

(n=

4)

reported

having

pain,

which

did

not

interfere

with

their

activities

but

could

not

be

easily

ignored

(but

still

not

sufficient

to

require

analgesia).

"

No

patients

reported

pain

that

interfered

with

their

daily

activities

or

chores,

required

analgesia

or

required

medical

attention.

The

proportion

of

patients

with

pain

in

the

week

prior

to

interview

was

5%

(95%

CI:

2%

to

7%

P<0.001)

(Table

2).

Of

those

who

reported

pain:

•

2.2%

(n

=

4)

reported

that

their

pain

did

not

interfere

with

their

normal

activities

and

could

be

easily

ignored.

•

3.2%

(n=

6)

reported

having

pain,

which

did

not

interfere

with

their

activities

but

could

not

be

easily

ignored

(but

still

not

sufficient

to

require

analgesia).

•

No

patients

reported

pain

that

interfered

with

their

daily

activities

or

chores,

required

analgesia

or

required

medical

attention.

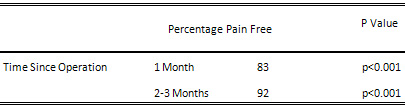

Resolution

of

pain

post-operatively

83%

(n

=154)

of

patients

were

pain

free

at

1

month

post

operatively,

and

92%

(n

=

170)

at

2-3

months

post-operatively

(Table

3).

Of

the

other

8%:

3%

had

intermittent

pain

that

lasted

for

6

months

(not

interfering

with

activities),

4%

of

patients

experienced

pain

for

up

to

12

months

(not

interfering

with

activities),

1%

had

pain

for

up

to

24

months

post-operatively.

Table

3:

Resolution

of

pain

post

operatively.

P

Values

calculated

when

cross-tabulated

against

preoperative

pain.

Post

Operative

Analgesia

Requirements

Patients

were

prescribed

paracetamol

and

codeine

tablets

(500mg

&

30mg

combination)

postoperatively,

and

were

advised

to

down

grade

to

the

500mg/8mg

combination

or

the

paracetamol

500mg

only

preparation

as

soon

as

pain

allowed

or

if

they

were

having

side

effects

from

the

analgesia.

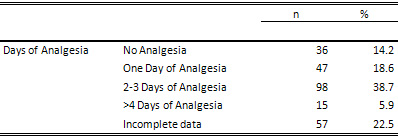

Table

4:

Post

Operative

Analgesia

Requirements

Functional

status

questions

(at

time

of

interview

and

previous

week)

•

100%

(n=185)

of

patients

had

no

pain

when

getting

up

from

a

low

chair.

•

97.8%

(n=180)

of

patients

reported

no

pain

when

sitting

for

more

than

half

an

hour.

•

98.4%

(n=182)

182

of

patients

did

not

experience

any

pain

or

discomfort

when

standing

for

more

than

half

an

hour.

•

98.9%

(n=183)

of

patients

were

able

to

go

up

and

down

stairs

without

experiencing

any

pain

in

the

groin.

•

98.4%

(n=182)

had

no

pain

when

driving.

Complications:

•

None

of

the

patients

with

significant

complications

developed

significant

chronic

pain

or

disability.

•

One

patient

re-operated

on

for

bleeding,

due

to

anti-coagulation

following

embolus,

had

occasional

discomfort.

•

One

patient

who

needed

removal

of

a

staple

from

the

mesh

had

no

further

pain

•

One

patient

who

required

prostatectomy

had

no

further

pain

•

Continuing

audit

over

many

years

showed

these

to

be

one

off

events

•

The

patients

with

seromas

and

superficial

infections

had

no

further

problems,

as

did

the

patients

who

developed

recurrences,

which

were

repaired.

Treatment

of

Nerves

The

IIN

was

identified

in

approximately

80%

of

cases.

In

approximately

10%

of

these

cases

when

the

nerve

was

identified

a

neurectomy

was

performed,

either

as

a

result

of

accidental

damage,

excessive

dissection

or

the

fear

of

entrapment

in

the

mesh.

The

IHN

was

identified

less

frequently

in

approximately

70%

of

cases.

It

was

divided

accidently

or

intentionally

in

approximately

10%

of

these

cases

mainly

to

avoid

entrapment

in

fixation

of

the

mesh

as

it

emerged

medially

from

the

internal

oblique

aponeurosis.

The

GFN

was

always

identified

with

the

cremasteric

vessels

and

only

divided

and

ligated

in

a

few

cases

when

these

vessels

were

ligated

for

technical

reasons.

The

vast

majority

of

unilateral,

bilateral

or

recurrent

hernia

patients

at

50

months

had

no

significant

pain

or

disability.

None

reported

that

their

exercise,

activities

or

work

were

limited

by

pain.

Few

reported

the

need

for

analgesia

on

any

consistent

basis.

The

incidence

of

moderate

or

significant

chronic

pain

was

less

than

1%,

which

the

authors

felt

would

be

pain

that

interfered

with

activities

or

required

regular

analgesia.

In

view

of

the

high

incidence

of

chronic

pain

and

disability

in

some

series(9)

there

have

been

many

attempts

to

identify

possible

risk

factors

and

surgical

materials

and

techniques

that

might

predict

its

development.

This

study,

because

of

the

low

incidence

of

chronic

pain

was

unable

to

identify

any

previously

reported

risk

factors,

despite

the

cohort

being

a

consecutive

series

of

patients.

The

authors

have

sought

to

analyze

and

explain

why

these

results

may

be

different

to

others.

The

wide

discrepancy

in

the

reported

incidence

of

chronic

pain

after

inguinal

hernia

repair

results

needs

to

be

explained

particularly

as

recommendations

may

be

based

on

these

results(12).

It

has

been

pointed

out

that

aggressive

early

therapy

for

post-operative

pain

is

indicated,

since

the

intensity

of

post-operative

pain

correlates

with

the

risk

of

developing

chronic

pain(15).

Pre-operative

LA

was

used

routinely

as

part

of

this

regime

ensuring

the

patient

is

pain

free

for

at

least

4-10

hours

and

is

able

to

travel

home

in

comfort

without

the

need

for

analgesics.

It

was

noted

in

this

series

that

the

vast

majority

of

the

patients

did

not

consider

early

post-operative

pain

to

be

a

major

factor.

The

use

of

post-operative

analgesics

was:

14%

needed

no

painkillers,

18%

used

pain

killers

for

1

day,

and

the

majority

for

just

a

few

days

to

a

week.

Even

those

who

felt

post-operative

pain

to

be

an

issue

did

not

develop

significant

chronic

pain.

Those

patients

who

did

complain

of

post-operative

pain

at

one

week

were

kept

under

review

until

the

pain

resolved.

The

low

incidence

of

significant

early

post-operative

pain

or

perceived

pain

and

the

minimal

need

for

analgesia

in

many

patients,

may

be

of

significance.

The

LA

may

contribute

to

this

early

low

level

of

pain

and

may

be

a

significant

factor,

particularly

as

pre-emptive,

peri-operative

and

post-operative

analgesia

considered

under

the

title

"multimodal

analgesia"

are

being

assessed

as

factors

in

preventing

chronic

pain(16).

Furthermore

with

LA

many

of

the

early

side

effects

of

general

anaesthesia

such

as

nausea,

vomiting,

and

acute

retention

of

urine

are

reduced.

Less

intensive

post-operative

nursing,

including

airway

care

is

required.

The

majority

of

patients

go

home

within

3

hours

of

surgery.

The

long

acting

LA

lasts

from

4-10

hours

and

many

patients

do

not

need

further

analgesia.

Many

patients

preferred

the

LA

because

of

previous

problems

with

general

anaesthesia.

Many

of

the

studies

of

the

Lichtenstein

method

have

not

used

local

anaesthesia

as

described

by

Lichtenstein.

This

may

diminish

the

benefits

of

the

original

repair

and

also

account

for

a

higher

incidence

of

chronic

pain

found

in

some

series.

The

nerves

The

management

of

the

3

major

nerves

of

the

inguinal

canal

has

been

considered

to

be

a

factor

in

chronic

pain(17).

This

study

showed

a

low

incidence

of

chronic

pain

despite

the

IIN

and

IHN

not

being

formally

identified

or

damaged

and

removed

in

up

to

20%

of

cases.

Extensive

studies

concluded

that

identification

and

preservation

of

all

3

nerves

of

the

inguinal

canal

reduces

chronic

incapacitating

groin

pain.

Mesh,

staples

Mesh

and

staples

have

also

been

widely

implicated

as

significant

factors

in

the

development

of

chronic

pain

leading

to

a

variety

of

new

lighter

weight

meshes,

staples

and

glues(16).

This

series

with

its

low

incidence

of

significant

chronic

pain

using

a

standard

Polypropylene

mesh

and

non-absorbable

staples

raises

the

question

as

to

the

role

of

the

mesh

in

the

development

of

chronic

pain.

Positive

Results

The

positive

results

identified

in

this

series

may

be

due

to

the

following

factors;

LA

infiltration

allowing

simpler

dissection

of

the

tissues

with

less

trauma.

Diathermy

is

not

used,

possibly

reducing

the

inflammatory

response

around

the

nerve

endings,

a

possible

cause

of

nocioceptive

pain.

Identification

and

management

of

the

nerves(12).

The

use

of

the

open

skin

stapler

to

fix

the

mesh

(appose

ulc

35w

auto

suture).

The

early

supervised

management

of

post-operative

pain,

including

contact

by

telephone

by

the

surgeon

with

all

patients

the

day

following

surgery

to

adjust

analgesia

and

give

support

as

necessary.

If

the

results

vary

so

much,

is

it

possible

to

attribute

chronic

pain

to

the

mesh/fixation

alone?

The

results

in

this

study,

suggest

that

mesh

and

staples

may

not

be

the

main

factors

in

determining

the

incidence

of

chronic

pain,

and

could

it

just

be

the

way

the

materials

are

used?

Does

it

depend

on

the

technique

and

the

surgeon?

There

is

strong

evidence

from

this

series,

using

a

validated

inguinal

pain

questionnaire,

that

a

Lichtenstein

repair

using

local

anaesthesia

can

achieve

a

low

incidence

of

chronic

post-operative

pain.

Those

few

patients

who

did

report

pain,

did

not

have

any

associated

significant

morbidity

or

impairment

of

activities

of

daily

living.

No

obvious

risk

factors

were

identified

as

predicting

or

associated

with

chronic

pain.

There

appeared

to

be

no

reason

to

alter

the

approach

used

to

manage

the

nerves,

the

type

of

mesh

or

its

method

of

fixation,

in

terms

of

chronic

pain.

The

validated

IPQ

provides

a

more

detailed

appreciation

of

pain

behaviour.

These

types

of

pain

measures

will

be

useful

in

the

future

to

help

in

assessing

the

role

of

surgical

risk

factors

and

techniques

as

a

cause

for

chronic

pain.

More

detailed

investigation

using

these

validated

tools

is

required

in

larger

prospective

studies,

to

provide

more

accurate

and

meaningful

comparisons

between

other

techniques

in

conjunction

with

greater

operator

experience.

1.

Kingsnorth

A,

LeBlanc

K.

Hernias:

inguinal

and

incisional.

Lancet.

Nov

8

2003;362(9395):1561-1571.

2.

Bisgaard

T,

Bay-Nielsen

M,

Christensen

IJ,

Kehlet

H.

Risk

of

recurrence

5

years

or

more

after

primary

Lichtenstein

mesh

and

sutured

inguinal

hernia

repair.

British

Journal

of

Surgery.

Aug

2007;94(8):1038-1040.

3.

Kehlet

H.

Chronic

pain

after

groin

hernia

repair.

British

Journal

of

Surgery.

Feb

2008;95(2):135-136.

4.

Poobalan

AS,

Bruce

J,

King

PM,

Chambers

WA,

Krukowski

ZH,

Smith

WC.

Chronic

pain

and

quality

of

life

following

open

inguinal

hernia

repair.

British

Journal

of

Surgery.

Aug

2001;88(8):1122-1126.

5.

Bay-Nielsen

M,

Nilsson

E,

Nordin

P,

Kehlet

H,

Swedish

Hernia

Data

Base

the

Danish

Hernia

Data

B.

Chronic

pain

after

open

mesh

and

sutured

repair

of

indirect

inguinal

hernia

in

young

males.

British

Journal

of

Surgery.

Oct

2004;91(10):1372-1376.

6.

Condon

RE.

Groin

pain

after

hernia

repair.

Annals

of

Surgery.

Jan

2001;233(1):8.

7.

Kehlet

H,

Bay-Nielsen

M,

Kingsnorth

A.

Chronic

postherniorrhaphy

pain--a

call

for

uniform

assessment.

Hernia.

Dec

2002;6(4):178-181.

8.

Dickinson

KJ,

Thomas

M,

Fawole

AS,

Lyndon

PJ,

White

CM.

Predicting

chronic

post-operative

pain

following

laparoscopic

inguinal

hernia

repair.

Hernia.

Dec

2008;12(6):597-601.

9.

Langeveld

HR,

van't

Riet

M,

Weidema

WF,

et

al.

Total

extraperitoneal

inguinal

hernia

repair

compared

with

Lichtenstein

(the

LEVEL-Trial):

a

randomized

controlled

trial.

Annals

of

Surgery.

May

2010;251(5):819-824.

10.

McCormack

K,

Scott

NW,

Go

PM,

Ross

S,

Grant

AM,

Collaboration

EUHT.

Laparoscopic

techniques

versus

open

techniques

for

inguinal

hernia

repair.

Cochrane

Database

of

Systematic

Reviews.

2003(1):CD001785.

11.

Franneby

U,

Gunnarsson

U,

Andersson

M,

et

al.

Validation

of

an

Inguinal

Pain

Questionnaire

for

assessment

of

chronic

pain

after

groin

hernia

repair.

British

Journal

of

Surgery.

Apr

2008;95(4):488-493.

12.

Simons

MP,

Aufenacker

T,

Bay-Nielsen

M,

et

al.

European

Hernia

Society

guidelines

on

the

treatment

of

inguinal

hernia

in

adult

patients.

Hernia.

Aug

2009;13(4):343-403.

13.

Franneby

U,

Sandblom

G,

Nordin

P,

Nyren

O,

Gunnarsson

U.

Risk

factors

for

long-term

pain

after

hernia

surgery.

Annals

of

Surgery.

Aug

2006;244(2):212-219.

14.

Lichtenstein

S,

Amid,

Montlor.

The

tension

free

hernioplasty

(1989)

American

Journal

Of

Surgery

157:188-193.

.

American

Journal

of

Surgery.

1989(157):188-193.

15.

Kehlet

H,

Jensen

TS,

Woolf

CJ.

Persistent

postsurgical

pain:

risk

factors

and

prevention.

Lancet.

May

13

2006;367(9522):1618-1625.

16.

Aasvang

EK,

Gmaehle

E,

Hansen

JB,

et

al.

Predictive

risk

factors

for

persistent

postherniotomy

pain.

Anesthesiology.

Apr

2010;112(4):957-969.

17.

Caliskan

K,

Nursal

TZ,

Caliskan

E,

Parlakgumus

A,

Yildirim

S,

Noyan

T.

A

method

for

the

reduction

of

chronic

pain

after

tension-free

repair

of

inguinal

hernia:

iliohypogastric

neurectomy

and

subcutaneous

transposition

of

the

spermatic

cord.

Hernia.

Feb

2010;14(1):51-55.

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|