DASH

Diet: How Much Time Does It Take to Reduce Blood

Pressure in Pre-hypertensive and Hypertensive

Group 1 Egyptian patients?

Rehab Abdelhai (1)

Ghada Khafagy (2)

Heba Helmy (3)

(1) Dr. Rehab Abdelhai (MD) is Associate Professor

of Public Health at Faculty of Medicine, Cairo

University

(2) Dr. Ghada Khafagy (MD) is lecturer of Family

Medicine, at Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University

(3) Dr. Heba Helmy (MSc) is a Family Physician

at Family Health Unit, Ministry of Health, Egypt.

Correspondence:

Dr. Ghada Khafagy, M.D.

Department of Family Medicine,

Faculty of Medicine,

Cairo University

71st, Moez El-Dwla, Makram Ebeed,

Nasr city, Cairo

Egypt

Phone: +20 - (0)100 - 6393140

Email: ghada.khafagy@kasralainy.edu.eg;

ghadakhafajy@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Background: Dietary

changes that lower blood pressure (BP)

have the potential to prevent hypertension

and more broadly to reduce BP, thus lowering

risks of BP-related complications. Evidence

shows that even a small reduction in BP

could have enormous benefits.

Objectives:

Evaluate the effect of Dietary Approaches

to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet on normotensive

individuals; pre-hypertension and hypertensive

grade 1 patients as well as to identify

time needed for DASH to reduce BP in pre-hypertension

and hypertensive grade 1 patients.

Methods: This

study was a prospective interventional

study carried out on 120 participants

attending the out-patient clinic of a

family medicine unit, of Dakahlia governorate,

Egypt. Participants were equally distributed

into three groups; normotensive, pre-hypertensive

hypertensive grade 1 participants (40

in each group). Blood pressure and weight

and waist circumference (WC) were measured

at the beginning of the study then every

2 weeks for 16 weeks.

Results: Significant

reductions in systolic and diastolic BP

among pre-hypertension by (8.1, and 16.4

mmHg respectively with P < 0.001) and

hypertensive participants by (5.8, and

7.4 mmHg respectively with P < 0.001)

were observed. Reduction was greater in

the first 8 weeks and reached a plateau

after 12 weeks. BP decrease in normotensive

group was insignificant. Additionally,

there was insignificant reduction in weight

and WC among the 3 groups.

Conclusion: Adherence

to DASH diet has rapid and statistically

significant improvement in systolic and

diastolic blood pressure in hypertensive

grade 1 and pre-hypertensive participants.

Hence, DASH diet was found effective as

a first line intervention of elevated

blood pressure.

Key Words: DASH,

Diet, Blood Pressure, Hypertension, Egypt

|

The prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension

among Egyptian adults has been reported as 57.2%

and 17.6% respectively. Only 25.2% of the population

had normal blood pressure levels of <120/80

mmHg. The highest prevalence of hypertension

was found in Ismailia, Alexandria, Menya, Menoufia

and Luxor governorates. The prevalence of hypertension

among males and females was similar; however,

females had a lower prevalence of prehypertension,

and a higher prevalence of normal blood pressure,

than males (1).

The STEPwise survey conducted in 2011-2012

recorded that the percentage of adult population

with raised blood pressure, or currently on

medication for hypertension (SBP

> 140 and/or DBP >

90 mmHg), was 39.4%, with females showing higher

percentage (40.8%) than males (38.7%). The percentage

of population with raised blood pressure increased

gradually with age, with the highest percentage

(80.5%) among the age group of 55-65 years.

Overall, the mean blood pressure was found to

be 128/82 mmHg which is considered to be the

state of pre-hypertension (2).

There is a gradual increase in cardiovascular

risk as blood pressure (BP) increases above

even "normal" values of 115/75 mmHg.

For individuals aged 40 to 70 years, each increase

of 20 mmHg of systolic BP or 10 mmHg of diastolic

BP doubles the risk of cardiovascular disease

(CVD). In controlled clinical trials, treatment

of hypertension reduces the risk of congestive

heart failure by 50%, stroke by 35% to 40% and

myocardial infarction by 20% to 25% ( 3).

Dietary factors have an important role in BP

homeostasis. In non-hypertensive and pre-hypertensive

individuals, dietary changes that lower BP have

the potential to prevent hypertension and more

broadly to reduce BP and thereby lower the risk

of BP-related complications. Even an apparently

small reduction in BP, if applied to an entire

population, could have an enormous beneficial

impact. It has been estimated that a 3 mm Hg

reduction in systolic BP could lead to an 8%

reduction in stroke mortality and a 5% reduction

in mortality from coronary heart disease. In

uncomplicated stage I hypertension, dietary

changes can serve as initial treatment before

the start of drug therapy. Among hypertensive

individuals who are already on drug therapy,

dietary changes, particularly a reduced salt

intake, can further lower BP and facilitate

medication step-down. Therefore, the extent

of BP reduction from dietary therapies is greater

in hypertensive than in non-hypertensive individuals

(4).

Although elevated blood pressure can be lowered

pharmacologically, antihypertensive medications

may be costly, must often be used in combination

to achieve adequate blood pressure control,

and can be associated with adverse effects that

impair quality of life and reduce adherence

(5). Although the Dietary Approaches to Stop

Hypertension (DASH) diet and other healthy lifestyle

changes may not be enough to control severe

high blood pressure, yet they often lead to

reduced need for blood pressure-lowering medications

as well as lower doses of those medications

(6).

The DASH diet emphasizes fruits, vegetables,

and low fat dairy products; whole grains, poultry,

legumes, fish, and nuts, and is reduced in fats,

red meat, sweets, and sugar-containing beverages.

It is therefore rich in potassium, magnesium,

calcium, and fiber and reduced in total fat,

saturated fat, and cholesterol. It is also characterized

by slightly increased protein content. It is

likely that several aspects of the DASH diet,

rather than just one nutrient or food, reduces

blood pressure (7).

This study aimed at testing the following

hypothesis: Adherence to DASH diet causes

a significant reduction in systolic and diastolic

BP in both study groups (pre-hypertension and

hypertensive group 1 patients), and a non-significant

reduction among normotensive group. Therefore,

DASH diet can cause even more improvement in

other risk factors of hypertension. Hence this

study aimed at answering the following research

questions: Does DASH diet have an effect on

systolic and diastolic blood pressure in normotensive

individuals, pre-hypertension and hypertensive

group 1 patients, and how much time does the

DASH diet need to decrease BP in pre-hypertensive

and hypertensive patients?

1- Evaluate the effect of DASH diet

on normotensive individuals; pre-hypertension

patients and hypertensive grade 1 patients.

2- Assess time needed for DASH diet to

reduce the blood pressure in pre-hypertension

patients and hypertensive grade 1 patients.

Study

design:

The

study

employed

a

prospective

interventional

design

to

evaluate

the

effect

of

Dietary

Approaches

to

Stop

Hypertension

(DASH)

diet

on

Normotensive,

Pre-hypertension

and

Hypertensive

grade

1

patients.

Study

site

and

subjects:

The

study

was

conducted

in

a

family

medicine

unit

(FMU)

that

provides

primary

health

care

services

in

the

rural

area

of

Sherbeen,

of

Dakahlia

governorate,

Egypt.

The

study

site

was

purposefully

selected

because

it

serves

7

villages,

with

different

socioeconomic

levels.

Additionally,

the

unit

has

a

high

rate

of

outpatient

visitors

(average

30

person/day)

seeking

different

medical

services.

The

health

unit

was

visited

on

three

days

per

week

regularly

from

June,

2012

till

February,

2013.

An

advertisement

was

distributed

throughout

the

FMU,

announcing

to

all

clients

the

subject

of

research

and

its

benefits

to

help

control

blood

pressure.

The

inclusion

criteria

for

study

participants

were

as

follows:

Age

between

30

-

60

years;

systolic

blood

pressure

<160

mmHg,

and

diastolic

blood

pressure

<100

mmHg;

both

sexes;

participants

willing

to

follow

the

advice

related

to

life

style

modifications.

Exclusion

criteria

for

the

study

participants

were:

Any

age

below

30

years,

or

above

60

years,

grade

2

hypertension

(systolic

>

160

mmHg,

diastolic

>

100

mmHg),

patients

with

terminal

organ

failure,

history

of

major

cardiovascular

events

(cerebrovascular

accidents),

patients

with

renal

disease,

pregnant

women,

patients

taking

medications

that

would

alter

blood

pressure

as

oral

contraceptives

pills,

corticosteroids,

hormonal

replacement

therapy,

anti-depressive

medications,

routine

use

of

aspirin

or

non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory

drugs.

.

Study

participants

were

then

classified

into

three

groups,

Group

1:

normotensive

group

with

(systolic

<

120

mmHg,

diastolic

<

80

mmHg);

Group

2:

pre

hypertensive

group

with

(systolic

120

-

139

mmHg,

diastolic

80

-

89

mmHg);

and

Group

3

hypertensive

grade

1

group

with

(systolic

140

-

159

mmHg,

diastolic

90

-99

mmHg).

The

grade

of

the

disease

was

identified

from

the

FMU

patient

records.

Initial

recruitment

of

subjects

started

then

follow-up

continued

for

the

next

16

weeks

(every

2

weeks).

All

participants

underwent

focused

medical

examination

for

initial

screening

before

recruitment.

Sample

Size

and

technique:

The

sample

size

was

calculated

according

to

the

flow

of

FMU

clients

as

obtained

from

the

FMU

records.

The

number

of

clients

ranged

between

20-30

per

day,

with

average

of

400-600

visitors

/month.

For

the

purposes

of

the

study,

every

participant

needed

half

an

hour

to

fill

out

the

questionnaire

and

to

measure

BP,

weight,

height,

and

waist

circumference.

Hence

10

participants

were

recruited

per

day.

Enrolment

stopped

when

the

number

of

subjects

recruited

reached

a

predetermined

sample

size

of

120

equally

distributed

among

the

study

groups.

Using

a

systematic

random

technique

over

the

working

days,

every

5th

patient

was

approached

and

asked

first

verbally

for

consent

to

undergo

initial

screening

and

participate

in

the

study

if

found

to

be

eligible.

All

patients

fulfilling

the

inclusion

criteria

were

asked

to

share

their

telephone

numbers

with

the

research

team

for

ease

of

follow

up.

Participants

were

recruited

for

an

initial

duration

of

5

weeks.

At

the

end

of

the

initial

recruitment

phase

a

total

of

120

individuals

were

recruited

(40

in

each

group).

Study

tools

and

measurements:

a-

Structured

questionnaire:

A

pre-coded

structured

questionnaire

was

used

to

assess

the

socio-demographic

characteristics,

dietary

and

behavioral

information

as

well

as

medical

information.

Demographic

data

included

(age,

gender,

education,

occupation,

marital

status).

Behavioral

and

dietary

information

included

alcohol

intake,

physical

activities,

food

taste

preferences,

cigarette

smoking,

and

frequency

of

intake

of

various

kinds

of

foods.

All

participants

were

asked

about

the

previous

3-day

food

record

prior

to

their

participation

in

the

study.

During

the

first

encounter,

participants

were

interviewed

to

assess

if

their

diet

was

unchangeable,

using

their

3-day

food

record

as

a

basis

for

their

habitual

diet.

For

example,

if

they

felt

unable

to

decrease

their

salt

intake

or

increase

their

fruit

and

vegetable

intake

sufficiently,

then

they

were

excluded

from

the

study.

A

total

of

120

participants

who

were

judged

capable

of

making

the

necessary

dietary

changes

were

recruited

into

the

study.

.

b-

Anthropometric

measurements:

Anthropometric

measurements

were

completed

using

standardized

procedures

and

were

documented

in

a

special

checklist

developed

for

the

purpose

of

the

study.

•

The

waist

circumference

(WC)

was

measured

to

the

nearest

0.1

cm

using

a

non-stretchable

measuring

tape

passing

halfway

between

the

lower

border

of

the

ribs

and

iliac

crest,

with

the

tape

horizontal

through

the

umbilicus.

WC

was

measured

every

month

for

the

subsequent

4

months

of

the

study.

•

Body

weight

(WT)

was

measured

to

the

nearest

50

gram;

subjects

were

in

light

clothing

without

shoes,

and

a

standard

balance

scale

was

used.

Height

(HT)

was

measured

with

subjects

standing

fully

erect

on

a

flat

surface

looking

straight

ahead,

with

heels,

buttocks

and

shoulders

flat

to

the

wall,

without

shoes;

measurements

were

to

the

nearest

0.5

centimeter,

and

a

tape

was

used.

The

body

mass

index

(BMI)

was

calculated

as

the

weight

in

(kilograms)

divided

by

the

height

in

(meters

squared)

(kg/m2).

•

The

Blood

pressure

was

measured

in

the

right

arm,

with

the

participant

in

a

seated

posture

with

feet

on

the

floor

and

arm

supported

at

heart

level,

after

at

least

5

minutes

of

rest

(8).

An

appropriate

size

of

cuff

and

a

standard

mercury

sphygmomanometer

were

used.

A

large

size

cuff

was

used

with

obese

participants.

Two

readings

each

of

systolic

BP

(SBP)

and

diastolic

BP

(DBP)

were

recorded;

Participants

were

advised

to

evacuate

bladder

and

to

stop

consuming

coffee,

tea,

or

smoking

cigarettes,

for

at

least

30

minutes

before

the

BP

readings.

These

measurements

with

the

same

precautions

were

repeated

every

2

weeks

for

the

subsequent

4

months

of

the

study.

All

the

sphygmomanometers

were

checked

and

calibrated

before

use.

Study

Intervention:

The

DASH

diet

tool

as

proposed

by

Hinderliter

et

al,

2011

(7),

was

used.

The

diet

was

explained

on

the

first

day,

and

started

the

following

day

for

16

weeks.

Subjects

were

requested

to

build

up

the

diet

during

the

first

week

of

the

study

period

to

the

required

number

of

portion

sizes

for

a

DASH-style

diet,

which

they

would

then

maintain

for

the

further

study

period.

This

was

done

to

minimize

the

gastrointestinal

side

effects

of

suddenly

increasing

non-starch

polysaccharide.

The

participants

were

asked

to

come

to

the

FMU

every

2

weeks

to

check

their

blood

pressure,

and

for

counseling

and

discussions

regarding

the

diet.

Energy

balance

was

aimed

for,

and

the

importance

of

maintaining

a

constant

body

weight

was

stressed.

The

study

diet

was

based

on

the

DASH

intermediate

sodium

diet

but

altered

to

fit

participant's

food

preferences

and

portion

sizes.

Greatest

emphasis

was

placed

on

consuming

the

fruits,

vegetables

and

low-fat

dairy

foods,

whole

grains,

poultry,

fish,

as

well

as

the

salt

restriction

and

weight

maintenance.

The

importance

of

reducing

saturated

fat,

red

meat

and

refined

carbohydrate

and

increasing

complex

carbohydrate

intakes

was

also

stressed.

Suggestions

on

how

to

increase

fruit

and

vegetable

consumption

were

also

provided.

All

smokers

were

advised

to

quit

smoking,

and

counseling

on

smoking

hazards

was

conducted.

Instructions

were

given

regarding

reducing

sodium

intake.

The

level

of

sodium

intake

that

was

aimed

for

was

2300

mg

or

less

(1

teaspoonful),

which

was

the

intermediate

level

used

in

the

DASH

sodium

trial

(9).

Subjects

were

requested

to

avoid

foods

with

a

high

salt

content

and

not

to

add

salt

during

cooking

or

at

the

table.

They

were

shown

how

to

interpret

food

labels,

particularly

with

regard

to

sodium

content.

Guidance

as

to

how

to

add

flavor

without

using

salt

was

given.

Subjects

were

requested

to

restrict

their

coffee

and

tea

intake

to

not

more

than

six

cups

a

day.

If

their

habitual

intakes

were

higher

than

these

levels,

they

were

asked

to

reduce

to

these

recommended

levels.

Under

participant's

request,

diets

were

organized

in

sheets

according

to

their

needs.

Subjects

were

requested

to

keep

their

exercises

as

usual

without

any

changes.

Data

management

and

statistical

analysis:

The

pre-coded

questionnaires

were

entered

for

analysis

on

SPSS

package

version

11.0.

for

quantitative

data

analysis.

Simple

frequencies

were

used

for

data

checking.

According

to

Joint

National

Committee

on

the

Prevention,

Detection,

Evaluation,

and

Treatment

of

High

Blood

Pressure

(10)

all

of

the

following

cut-off

points

were

used

in

the

study:

•

Age

of

study

participants

was

categorized

into

2

age

groups,

below

35

years

old

and

above

35

years

old.

•

Hypertension

was

identified

according

to

the

following

criteria:

-

Normotensive

group

(systolic

<

120

mmHg,

diastolic

<

80

mmHg),

-

Pre-hypertension

group

(systolic

120

-

139

mmHg,

diastolic

80

-

89

mmHg),

-

Hypertensive

grade

1

(systolic

140

-

159

mmHg,

diastolic

90

-

99

mmHg).

Compliance

with

Ethical

Standards:

The

study

was

approved

by

the

Family

Health

and

Public

Health

Councils.

Selected

members

constituted

the

internal

review

board

to

guarantee

the

ethical

conformity

of

the

study.

Informed

verbal

consent

was

obtained

from

all

the

participants

before

recruitment

in

the

study,

after

explaining

the

objectives

of

the

work

and

procedures.

All

questionnaire

forms

and

clinical

sheets

were

coded

to

preserve

confidentiality

that

was

also

guaranteed

on

handling

the

data

base

according

to

the

revised

Helsinki

declaration

of

biomedical

ethics

(11).

All

participants

were

informed

about

the

results

of

their

medical

examination.

Those

who

were

found

hypertensive

grade

2

were

referred

to

the

unit

health

team

for

drug

prescription,

and

further

follow

up.

The

study

included

120

participants

of

which

56.7%

were

females.

Participants

were

equally

distributed

among

the

study

groups.

The

mean

age

of

participants

in

the

hypertensive

group

was

found

to

be

significantly

older

than

those

in

the

other

two

study

groups

with

a

mean

age

of

45.5

±

7.7

years

compared

to

39.5

±

8.3years

and

40.2

±

7.8

years

for

participants

in

the

normotensive

and

pre-hypertension

groups,

respectively

(P

=

0.001).

The

age

of

most

of

the

study

participants

were

more

than

35

years

old

(72.5%)

of

which

28.7%

were

normotensive,

31.1%

were

pre-hypertension

and

40.2%

were

hypertensive.

Only

46.6%

of

all

participants

had

higher

education,

of

which

32.1%

were

normotensive,

39.3%

were

pre-hypertension

and

28.6%

were

hypertensive.

Moreover

41.7%

of

all

participants

had

basic

education,

of

which

34.0%

were

normotensive,

28.0%

were

pre-hypertension

and

35.7%

were

hypertensive.

There

was

no

significant

difference

between

the

study

groups

regarding

gender,

marital

status,

education

or

occupation

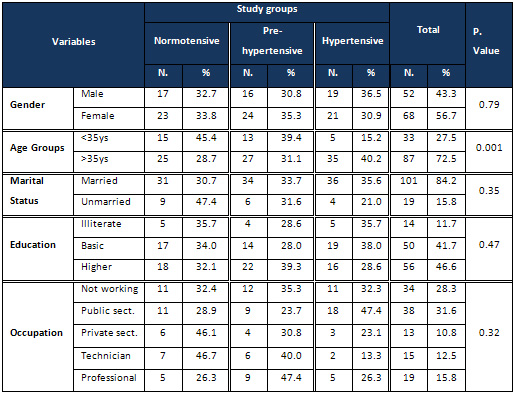

[Table

1].

Table

1:

Socio-demographic

characteristics

of

the

study

participants

As

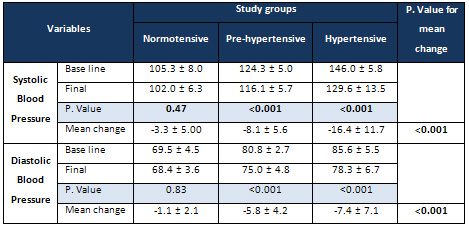

regards

systolic

blood

pressure

(SBP)

readings,

the

base

line

reading

for

normotensive

group

was

105.3

±

8.0

mmHg,

and

then

at

the

end

of

the

study

it

became

102.0

±

6.3

mmHg,

with

mean

change

3.3

±

5.0

mmHg.

For

the

pre-hypertension

group,

it

was

124.3

±

5.0

mmHg.

That

became

116.1

±

5.7

mmHg,

with

mean

change

8.1

±

5.6

mmHg.

As

for

the

hypertensive

group

it

was

146.0

±

5.8

mmHg,

and

became

129.6

±

13.5

mmHg,

with

mean

change

16.4

±

11.7

mmHg.

Although

there

was

no

significant

change

in

the

normotensive

group

readings

(P

=

0.47),

there

were

statistically

significant

changes

in

pre-hypertension

and

hypertensive

readings

(P

<0.001).

When

comparing

the

mean

change

in

systolic

blood

pressure

readings

among

all

study

groups,

a

highly

significant

difference

was

detected

(P

<

0.001)

with

the

hypertensive

group

showing

the

highest

reduction

followed

by

the

other

two

groups.

This

difference

was

found

across

the

three

groups

[Table

2].

Table

2:

Effect

of

DASH

diet

on

mean

systolic

and

diastolic

blood

pressure

readings

among

the

study

groups

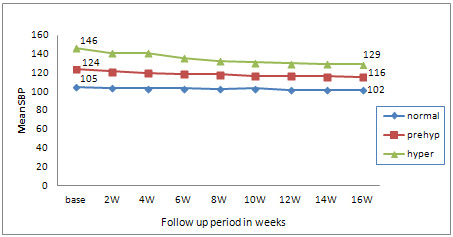

Figure

1

displays

the

mean

SBP

readings

for

the

study

groups,

across

the

follow

up

period

of

the

study.

The

effect

of

DASH

diet

was

most

evident

on

the

hypertensive

group,

where

the

mean

SBP

was

reduced

from

146

mmHg

at

base

line

to

129.6

mmHg

at

the

end

of

16

weeks

and

this

reduction

reached

a

plateau

at

12

weeks.

Figure

1:

Follow

up

of

mean

systolic

blood

pressure,

among

study

groups,

during

the

duration

of

the

study

Regarding

the

diastolic

blood

pressure

(DBP)

readings,

the

base

line

reading

for

the

normotensive

group

was

69.5

±

4.5

mmHg

that

became

at

the

end

of

the

study

68.4

±

3.6

mmHg,

with

mean

change

1.1

±

2.1

mmHg.

Similarly

it

was

80.8

±

2.7

mmHg,

then

75.0

±

4.8

mmHg,

for

pre-hypertension

group

with

mean

change

5.8

±

4.2

mmHg,

and

was

85.6

±

5.5

mmHg

then

78.3

±

6.7

mmHg

with

mean

change

7.4

±

7.1mmHg

for

hypertensive

group.

There

was

no

significant

change

in

normotensive

group

readings

(P

=

0.83),

however,

there

was

a

significant

change

in

pre-hypertension

and

hypertensive

groups

(P

<

0.001).

Comparing

the

mean

change

in

diastolic

blood

pressure,

a

highly

significant

difference

was

detected

(P

<

0.001).

The

hypertensive

group

showed

the

highest

reduction,

followed

by

the

other

two

groups.

The

difference

was

found

between

the

hypertensive

and

pre-hypertension

groups

in

comparison

to

the

normotensive

group

[Table

2].

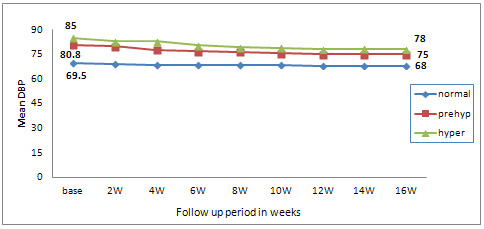

Figure

2

shows

the

mean

DBP

readings

for

the

study

groups

across

the

follow

up

period

of

the

study.

Both

the

hypertensive

and

the

pre-hypertension

groups

started

at

above

80

mmHg

and

reached

78.3

mmHg

and

75.0

mmHg

respectively,

at

the

end

of

the

study

period

with

a

plateau

at

12

weeks.

Figure

2:

Follow

up

of

diastolic

blood

pressure,

among

study

groups

during

the

duration

of

the

study

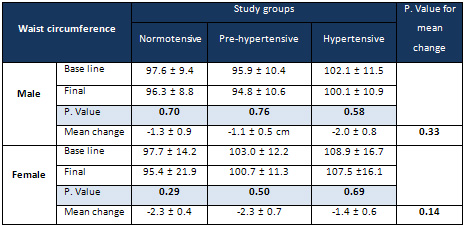

The

mean

waist

circumference

(WC)

among

males

in

the

normotensive

group

at

base

line

was

97.6

±

9.4

cm,

and

then

became

96.3

±

8.8

cm

at

the

end

of

the

study.

Similarly

WC

was

95.9

±

10.4

cm

for

the

pre-hypertension

group,

that

became

94.8

±

10.6

cm,

and

was

102.1

±

11.5

cm,

then

became

100.1

±

10.9

cm

for

the

hypertensive

group

[Table

3].

Although

there

was

a

slight

mean

decrease

in

the

mean

male

WC

of

the

base

line

reading

by

about

1.3

±

0.9

cm,

1.1

±

0.5

cm,

2.0

±

0.8

cm

in

normotensive,

pre-hypertension,

hypertensive

groups

respectively,

there

was

no

statistically

significant

difference

in

the

male

waist

circumference

response.

The

mean

WC

for

females

at

base

line

was

97.7

±

14.2

cm,

to

end

at

95.4

±

21.9

cm

for

the

normotensive

group.

As

for

the

pre-hypertension

group

it

was

103.0

±

12.2

cm,

that

became

100.7

±

11.3

cm,

and

it

was

108.9

±

16.7

cm,

and

became

107.5

±

16.1

cm

for

the

hypertensive

group

[Table

3].

A

slight

decrease

in

the

mean

female

WC

base

line

readings

by

2.3

±

0.4

cm,

2.3

±

0.7

cm

1.4

±

0.6

cm

in

normotensive,

pre-hypertension,

hypertensive

groups

respectively

was

found,

however

these

findings

were

statistically

insignificant.

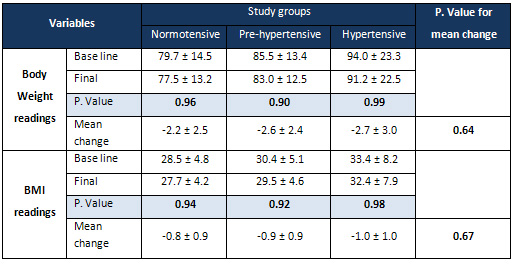

Similar

findings

with

reductions

in

body

weight

and

body

mass

index

were

detected

although

these

were

also

statistically

insignificant

[Table

4].

Table

3:

Effect

of

DASH

diet

on

waist

circumference

of

males

and

females

of

the

study

groups

Table

4:

Effect

of

DASH

diet

on

mean

body

weight

and

body

mass

index

readings

among

the

study

groups

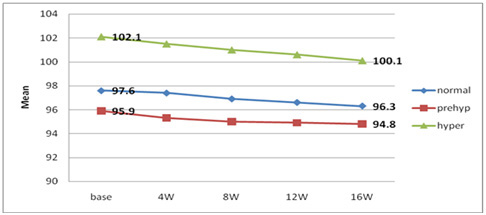

Figure

3:

Follow

up

of

mean

male

waist

circumference,

by

study

groups

Figure

3

shows

the

mean

male

WC

readings

for

the

study

groups

across

the

follow

up

period

of

the

study.

Both

the

hypertensive

and

the

pre-hypertension

groups

started

at

above

97

cm

and

reached

100.1

and

96.3

cm

respectively,

at

the

end

of

the

study

period.

Although

the

decrease

in

WC

was

insignificant,

it

continued

throughout

the

14

weeks.

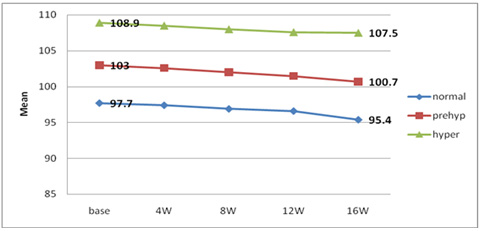

Figure

4:

Follow

up

of

female

mean

waist

circumference,

by

study

groups

Figure

4

shows

the

mean

female

WC

readings

for

the

study

groups

across

the

follow

up

period

of

the

study.

Both

the

hypertensive

and

the

pre-hypertension

groups

started

at

above

103cm

and

reached

100.7

and

107.5

cm

respectively,

by

the

end

of

the

study

period.

The

decrease

in

WC

was

also

insignificant

but

continued

throughout

the

14

weeks.

The

National

Institutes

of

Health,

in

the

USA,

developed

the

Dietary

Approaches

to

Stop

Hypertension

(DASH)

eating

plan,

which

has

been

shown

to

reduce

blood

pressure

and

body

weight

as

well

as

prevent

chronic

diseases

(12).

This

study

explored

the

effects

of

a

DASH

diet

intervention

among

three

groups

of

Egyptian

patients.

Reductions

in

both

systolic

and

diastolic

blood

pressure

readings

were

found

in

all

groups

of

normotensive,

pre-hypertension

and

hypertensive

grade

1

participants.

However,

reductions

were

significantly

greater

among

the

hypertensive

grade

I

and

pre-hypertensive

group

compared

to

the

normotensive

group.

These

findings

concur

with

results

of

Getchell

et

al,

1999

where

459

adults

who

were

hypertensive

and

non-hypertensive

were

included

and

the

study

applied

three

types

of

diets:

(1)

a

control

diet

with

a

nutrient

composition

typical

of

that

consumed

by

Americans;

(2)

a

DASH

diet

rich

in

fruits,

vegetables,

and

low

fat

dairy

products

with

a

reduced

amount

of

saturated

fat,

total

fat,

and

cholesterol

and

a

modestly

increased

amount

of

protein;

and

(3)

a

diet

rich

in

fruits

and

vegetables

but

otherwise

similar

to

the

control

diet.

It

was

found

that

in

comparison

to

the

control

group,

blood

pressure

reduction

was

greater

in

those

who

were

hypertensive

on

entry

to

the

study.

Additionally,

for

participants

following

the

DASH

diet,

the

amount

of

blood

pressure

reduction

increased

significantly

as

baseline

blood

pressure

increased

(13).

In

addition,

the

study

of

Harnden

et

al,

2010

that

applied

a

DASH

diet

for

30

days

in

the

UK

showed

a

weight

reduction

with

an

associated

significant

reduction

in

the

mean

systolic

and

diastolic

blood

pressure

(14).

As

regards

the

effect

of

DASH

and

time

to

reduction

of

both

systolic

and

diastolic

blood

pressure,

findings

of

our

study

showed

major

significant

reductions

in

the

BP

among

pre-hypertensive

and

hypertensive

group

1

patients

were

greater

in

the

first

8

weeks

reaching

a

plateau

after

12

weeks

till

the

end

of

the

study.

Similar

results

were

reported

by

Craddick

et

al,

2003

who

found

that

DASH

diet

quickly

and

significantly

reduces

blood

pressure,

in

comparison

to

the

control

(ordinary)

diet

among

adults

diagnosed

as

pre-hypertensive

and

hypertensive

grade

1.

These

results

were

obtained

without

requiring

participants

to

lose

weight

or

reduce

their

sodium

intake

(15).

Earlier

Vollmer

et

al,

2001

reported

on

proven

strategies

for

reducing

blood

pressure

as

confirming

the

DASH

diet,

and

reducing

sodium

intake

among

other

strategies.

Adopting

each

alone

or

in

combination

would

reduce

the

risks

of

high

blood

pressure.

However,

this

requires

long-term

commitment

and

significant

lifestyle

change

to

be

effective

(16).

In

2007,

Dauchet

et

al,

found

in

a

cross-sectional

analysis,

that

measured

intake

of

fruits,

vegetables,

and

dairy

products

which

are

the

components

of

DASH

diet,

are

associated

with

a

lowered

systolic

blood

pressure

by

1.5

mmHg

and

diastolic

blood

pressure

by

1.4

mmHg

(17).

In

our

study,

there

was

a

slight

decrease

in

the

mean

WC

in

normotensive,

pre-hypertension,

hypertensive

groups.

Although

this

was

insignificant

yet

it

continued

throughout

the

14

weeks

of

the

study.

Additionally,

slight

reductions

were

also

found

regarding

body

weight

and

BMI

following

compliance

to

the

DASH

diet

that

although

insignificant,

may

have

also

helped

in

reducing

blood

pressure

among

study

participants.

Data

from

the

ENCORE

study

suggest

that

the

DASH

eating

plan

alone

lowers

blood

pressure

in

overweight

individuals

with

high

blood

pressure,

but

significant

improvements

in

insulin

sensitivity

are

observed

only

when

the

DASH

diet

is

implemented

as

part

of

a

more

comprehensive

lifestyle

modification

program

that

includes

exercise

and

weight

loss

(18).

DASH

is

thus

preferred

as

the

initial

approach

to

treating

most

individuals

with

uncomplicated

higher

than

optimal

blood

pressure.

Various

DASH

studies

have

demonstrated

that

the

total

eating

pattern,

including

sodium

and

other

nutrients

and

foods,

affects

blood

pressure

and

is

also

associated

with

a

reduced

risk

of

cardiovascular

disease

and

lowered

mortality

(12,

19).

This

study

provides

evidence

for

the

beneficial

health

outcomes

among

adults

that

have

confirmed

our

intervention.

Results

have

shown

that

DASH

diet

reduces

blood

pressure

among

all

participants

but

with

more

effect

among

those

with

higher

blood

pressure

levels.

DASH

diet

as

a

monotherapy

is

known

to

be

an

effective

and

rapid

initial

treatment

for

patients

with

mild

hypertension.

As

an

intervention,

it

alleviates

the

cost

and

side

effects

associated

with

antihypertensive

medications,

ultimately

improving

a

patient's

quality

of

life.

Therefore,

the

study

recommends

that

family

physicians

begin

with

it

as

a

first

step

for

primary

prevention

or

secondary

prevention

in

mildly

uncomplicated

hypertensive

patients

and

determine

its

efficacy

after

8

-12

weeks.

While

other

lifestyle

modifications

such

as

smoking

cessation

require

greater

time

and

personal

effort,

adherence

to

the

DASH

diet

program

can

be

encouraged

through

health

education,

enhancing

family

support

and

frequent

counseling.

1.

Arafa

NAS,

and

Ez-Elarab

HS

(2011).

Epidemiology

of

Prehypertension

and

Hypertension

among

Egyptian

Adults.

The

Egyptian

Journal

of

Community

Medicine;

29

(1):

1-18

2.

World

health

Organization,

(2012)

Egypt;

Noncommunicable

diseases

risk

factor

survey.

STEPwise

2011

-

2012.

World

Health

Organization

-

Egypt

Country

Office

In

collaboration

with

Ministry

of

Health

and

Population

-

Egypt.

Available

at:

http://www.who.int/chp/steps/2011-2012_Egypt_FactSheet.pdf

3.

Pearce

KA

and

Dassow

P

(2008).

In

Taylor's

manual

of

family

medicine,

3rd

Edition.

9.1

Hypertension.

Lippincott

Williams&

Wilkins.

Pg

284-291.

4.

Appel

LJ

(2010).

DASH

Position

Article:

Dietary

approaches

to

lower

blood

pressure.

On

behalf

of

the

American

Society

of

Hypertension

Writing

Group.

Journal

of

the

American

Society

of

Hypertension;

4

(2):

79-89.

Available

at:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jash.2010.03.004

5.

Neal

B,

MacMahon

S,

Chapman

N.

(2000).

Effects

of

ACE

inhibitors,

calcium

antagonists,

and

other

blood-pressure-lowering

drugs:

results

of

prospectively

designed

overviews

of

randomised

trials.

Blood

Pressure

Lowering

Treatment

Trialists'

Collaboration.

Lancet.

;

356:

1955-1964.

6.

Svetkey

L

P.,

Morton

DS.

,

Vollmer

W

M.,

et

al

(1999).

Effects

of

Dietary

Patterns

on

Blood

Pressure

Subgroup

Analysis

of

the

Dietary

Approaches

to

Stop

Hypertension

(DASH)

Randomized

Clinical

Trial,

Arch

Intern

Med.:

159(3):285-293.

7.

Hinderliter

AL,

Babyak

MA,

Sherwood

A

and

Blumenthal

JA

(2011).

The

DASH

Diet

and

Insulin

Sensitivity.

Curr

Hypertension

Rep

13:

67-73.

8.

Ataman

SL,

Cooper

R,

Rotimi

C,

et

al

(1996).

Standardization

of

blood

pressure

measurements

in

an

international

comparative

study.

J

Clin

Epidemiology;

49(8):

869-877.

9.

Sacks

F

M,

Svetkey

L

P,

Vollmer

W

M,

et

al

(2001).

DASH-Sodium

Collaborative

Research

Group.

Effects

on

blood

pressure

of

reduced

dietary

sodium

and

the

Dietary

Approaches

to

Stop

Hypertension

(DASH)

diet.

N

Engl

J

Med.;

344(1):3-10.

10.

Joint

National

Committee

on

the

Prevention,

Detection,

Evaluation,

and

Treatment

of

High

Blood

Pressure

(2003).

The

Seventh

Report

of

the

Joint

National

Committee

on

the

Prevention,

Detection,

Evaluation,

and

Treatment

of

High

Blood

Pressure:

the

JNC

7

report.

JAMA;

289:

2560-72.

11.

World

Medical

Association

(2008):

The

Declaration

of

Helsinki.

Available

at:

http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html

12.

U.S.

Department

of

Agriculture

and

U.S.

Department

of

Health

and

Human

Services.

Dietary

Guidelines

for

Americans,

2010.

7th

Edition,

Washington,

DC:

U.S.

Government

Printing

Office,

December

2010.

Available

at:

http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/dietaryguidelines2010.pdf

13.

Getchell

WS,

Svetkey

LP,

Appel

LJ,

Moore

TJ,

Bray

GA,

Obarzanek

E

(1999).

Summary

of

the

Dietary

Approaches

to

Stop

Hypertension

(DASH)

Randomized

Clinical

Trial

Current

Treatment

Options

in

Cardiovascular

Medicine,

1:

295

-

298.

14.

Harnden

KE,

Frayn

KN

and

Hodson

L

(2010).

Dietary

Approaches

to

Stop

Hypertension

(DASH)

diet:

applicability

and

acceptability

to

a

UK

population

Journal

of

Human

Nutrition

and

Dietetics.

The

British

Dietetic

Association

Ltd.,

23,

pp.

3-10.

15.

Craddick

SR,

Elmer

PJ,

Obarzanek

E,

Vollmer

WM,

Svetkey

LP

and

Swain

MC

(2003).

The

DASH

Diet

and

Blood

Pressure,

Current

Atherosclerosis

Reports,

5:484-491.

16.

Vollmer

WM,

Sacks

FM,

Svetkey

LP

(2001).

New

insights

into

the

effects

on

blood

pressure

of

diets

low

in

salt

and

high

in

fruits

and

vegetables

and

low-fat

dairy

products

Current

Controlled

Trials

in

Cardiovascular

Medicine:

2(2):71-74

17.

Dauchet

L,

Kesse-Guyot

E,

Czernichow

S,

et

al

(2007).

Dietary

patterns

and

blood

pressure

change

over

5-y

follow-up

in

the

SU.VI.MAX

cohort.

Am

J

Clin

Nutr.;

85(6):1650-1656.

18.

Blumenthal

JA,

Babyak

MA,

Sherwood

A,

et

al.

(2010).

Effects

of

the

Dietary

Approaches

to

Stop

Hypertension

diet

alone

and

in

combination

with

exercise

and

caloric

restriction

on

insulin

sensitivity

and

lipids.

Hypertension.;

55:

1199-1205.

19.

Sacks,

FM,

Obarzanek,

E,

Windhauser,

M,

Svetkey,

L,

Vollmer,

W,

McCullough,

M,

Karanja,

N,

Lin,

P-H

et

al.

(1995).

Rationale

and

design

of

the

Dietary

Approaches

to

Stop

Hypertension

trial

(DASH).

Annals

of

Epidemiology;

5

(2):

108-118.

|