|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor) |

|

|

|

|

........................................................

|

Original

Contribution/Clinical Investigation

|

|

|

<-- Abu Dhabi -->

Knowledge,

attitude and behaviour of asthmatic patients

regarding asthma in primary care setting in

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

[pdf version]

Osama Moheb Ibrahim Mohamed, Wael Karameh Karameh

<-- Egypt -->

DASH Diet: How

Much Time Does It Take to Reduce Blood Pressure

in Pre-hypertensive and Hypertensive Group 1

Egyptian patients?

[pdf version]

Rehab Abdelhai, Ghada Khafagy, Heba Helmy

<-- Egypt -->

Assessment of TB

stigma among patients attending chest hospital

in Suez Canal University area, Egypt

[pdf version]

Nahed Amen Eldahshan, Rehab Ali Mohammed, Rasha

Farouk Abdellah, Eman Riad Hamed

<-- Egypt -->

Awareness

of diabetic retinopathy in Egyptian diabetic

patients attending Kasra Al-Ainy outpatient

clinic: A cross-sectional study

[pdf version]

Marwa Mostafa Ahmed, Mayssa Ibrahim Ali, Hala

Mohamed El-Mofty, Yara Magdy Taha

<-- Iraq -->

Estimation of

some biophysical parameters in semen of fertile

and infertile patients

[pdf version]

Dhahir Tahir Ahmad, Suhel Mawlood Alnajar, Tara

Nooradden Abdulla, Zhyan Baker Hasan

|

|

........................................................ |

Medicine and Society

|

|

<-- Iraq -->

Celebrating lives

from the Region

[pdf version]

Lesley Pocock

<-- Regional/International -->

Health

Promotion, Disease Prevention and Periodic Health

Checks: Perceptions and Practice among Family

Physicians in Eastern Mediterranean Region

[pdf version]

Waris Qidwai, Kashmira Nanji, Tawfik A M Khoja,

Salman Rawaf, Nabil Yasin Al Kurashi, Faisal

Alnasir, Mohammed Ali Al Shafaee, Mariam Al

Shetti,Nagwa Eid Sobhy Saad, Sanaa Alkaisi,

Wafa Halasa, Huda Al-Duwaisan, Amal Al-Ali

<--

Australia/Iran -->

Virology

vigilance - an update on MERS and viral mutation

and epidemiology for family doctors

[pdf version]

Lesley Pocock, Mohsen

Rezaeian

|

........................................................

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| July / August

2015 - Volume 13 Issue 5 |

|

Assessment

of TB stigma among patients attending chest hospital

in Suez Canal University area, Egypt

Nahed Amen Eldahshan (1)

Rehab Ali Mohamed (1)

Rasha Farouk Abdellah

(2)

Eman Riad Hamed

(3)

(1) Lecturer ofFamily medicine, Faculty of medicine,

Suez Canal University

(2) Lecturer of occupational Health, Faculty

of medicine, Suez Canal University

(3) Lecturer of chest diseases and tuberculosis,

Faculty of medicine, Suez Canal University

Correspondence:

Dr. Nahed

Amen Eldahshan

Lecturer family medicine

Faculty of medicine, Suez Canal University

Ismailia city, Egypt

Mobile: 01222626824

Email:

nahed.eldahshan@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Background: TB

stigmatization is a complex process involving

institutions, communities, and inter-

and intra-personal attitudes. While it

has been recognized as an important social

determinant of health and health disparities,

the difficulties in identifying, characterizing,

measuring, and tracking changes in stigmatization

over time have made it challenging to

justify devoting resource intensive interventions

to the problem.

Objectives: To

identify the magnitude and the burden

of TB stigma on patient and effect of

TB stigma on treatment adherence.

Methods: The

data were collected between August and

December 2014, recruiting all patients

who had commenced treatment for up to

a month. All patients were subjected to

personal detailed interview according

to a predesigned questionnaire after taking

informed consent of the patients.

Results: A

total of 53 patients consented to participate.

The mean age ± SD was 43 ±

14.1 years. Out of the total number, 22.6%

were illiterate and 77.4% were literate.

As regards occupation, 69.8% were independent

and 30.2% were dependent. The stigma prevalence

among TB patients was found to be 41.5%.

Stigma is more prevalent among the younger

age group (43.5 %), males (43.9 %) and

among married patients (46.7%). There

was an immense stigma observed among urban

residence (57.7 %), current smokers (60.0

%) and those who had two or less rooms

in their house (66.7 %) and this was found

to have a statistically significant difference

(P<0.05). The majority of patients

(67.9%) take treatment regularly.

Conclusion: TB

stigma has been raised as a potential

barrier to home and work-based direct

observational therapy (DOT). Perceived

TB stigma had no effect on treatment regularity.

Health education programs should be conducted

to reduce TB stigma and improve patients'

compliance.

Key words : TB

stigma, prevalence , treatment adherence

|

Tuberculosis (TB) is believed to be nearly

as old as human history. Traces of it in Egyptian

mummies date back to about 7000 years ago, when

it was described as phthisis by Hippocrates(1).

It was declared a public health emergency in

the African Region in 2005 and has since continued

to be a major cause of disability and death(2).

About 9.4 million new cases of tuberculosis

were diagnosed in 2009 alone and 1.7 million

people reportedly died from the disease in the

same year, translating to about 4700 deaths

per day (2). About one-third of the world's

population (estimated to be about 1.75 billion)

is infected with the tubercle bacillus(3). As

much as 75% of individuals with TB are within

the economically productive age group of 15

to 54 years. This significantly impairs socioeconomic

development, thereby perpetuating the poverty

cycle (4).

The social determinants of health refer to

the institutional, community, and interpersonal

factors that affect health outside of the ease

with which an individual can access medical

services (5). Stigma, which is shaped and promulgated

by institutional and community norms and interpersonal

attitudes, is a social determinant of health(6).

Stigma is a process that begins when a particular

trait or characteristic of an individual or

group is identified as being undesirable or

disvalued(7). The stigmatized individual often

internalizes this sense of disvalue and adopts

a set of self-regarding attitudes about the

marked characteristic including shame, disgust,

and guilt (8). These attitudes produce a set

of behaviors that include hiding the stigmatized

trait, withdrawing from interpersonal relationships,

or increasing risky behavior (9-10).

Stigmatization is conceptually distinct from

discrimination, another social determinant of

health in that the primary goal of discrimination

is exclusion, not necessarily for the target

to feel ashamed or guilty(11-12). Stigmatized

individuals can, however, suffer discrimination

and status loss at the hands of the broader

community, whose norms have caused them to be

perceived as undesirable (7-13). Stigmatization

is a complex process involving institutions,

communities, inter- and intra-personal attitudes.

While it has been recognized as an important

social determinant of health and health disparities,

the difficulties in identifying, characterizing,

measuring, and tracking changes in stigmatization

over time have made it challenging to justify

devoting resource intensive interventions to

the problem(6-14). One exception is human immunodeficiency

virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

(AIDS) research, where the interactions among

stigma, HIV risk behaviors, and HIV associated

outcomes have been fairly well characterized(15-16).

Substantially less study has been conducted

on the mechanisms through which stigma impacts

the health of individuals at risk for or infected

with TB. From its introduction in 1994, DOTS

has been the backbone of TB control around the

world. With its focus on passive case detection,

availability of diagnostic techniques, and directly

observed therapy to minimize drug resistant

TB, DOTS has been criticized as a treatment

guideline and biomedical strategy that does

not account for social factors related to TB

control rather than a comprehensive control

plan (17-18).

Delay in presentation to a health facility

is an important concern as it contributes to

delays in initiating TB treatment. This can

result in greater morbidity and mortality for

the patient and increased transmission of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis in the community(19-20). There

is a large body of literature on factors associated

with delay in seeking care for TB symptoms.

These can be broadly grouped into access to

care, personal characteristics, socioeconomic,

clinical, TB knowledge or beliefs, and social

support or psychosocial factors(21). One psychosocial

factor of interest is health-related stigma,

often defined as a social process "characterized

by exclusion, rejection, blame, or devaluation

resulting from experience or reasonable anticipation

of an adverse social judgment" because

of a particular health condition (22). Some

studies have suggested that TB stigma could

lead to delays in patients seeking appropriate

medical care (19-23).

To

highlight

the

importance

of

psychosocial

factor

on

TB

stigma,

aiming

to

improve

the

quality

of

care

for

TB

patients.

To

identify

the

magnitude

and

the

burden

of

TB

stigma

on

patients

received

TB

treatment

and

to

determine

socio

demographics

factors

associated

with

TB

stigma.

This

was

a

cross

sectional

study

conducted

at

two

government

health

institutions

providing

TB

services

in

the

Suez

Canal

area.

The

treatment

regimens

used

throughout

the

country

are

based

on

the

World

Health

Organization's

(WHO)

Directly

Observed

Treatment,

ShortCourse

(DOTS)

strategy.

The

data

were

collected

between

August

and

December

2014,

recruiting

allpatients

who

had

commenced

treatment

for

up

to

a

month.

All

patients

were

subjected

to

personal

detailed

interview

according

to

a

predesigned

questionnaire

after

taking

informed

consent

of

the

patients.

Before

conducting

the

study,

the

questionnaire

was

pre-tested

and

evaluated

for

proper

conduct

of

the

study.

The

information

was

elicited

from

TB

patients

regarding

'problems

faced

in

their

homes,

neighbours'

attitudes

and

friends.

Questionnaire

included

questions

regarding

data

on

socioeconomic

issues

and

awareness

of

TB

and

the

nature

of

their

disclosure

of

their

disease

to

family

members.

The

information

was

also

elicited

regarding

behavioral

changes

such

as

maintaining

appropriate

personal

distance

and

avoiding

close

contact

in

activities

with

family

members,

neighbours,

friends

and

other

fellow

employees.

The

data

were

entered,

cleaned

and

analyzed

using

SPSS

software

version

18.0.

Descriptive

statistics

like

frequency

distribution

and

percentage

calculation

was

made

for

most

of

the

variables.

Chi

square

test

and

proportion

tests

were

used

to

assess

significance.

A

value

of

p<0.05

was

taken

as

significant.

Ethical

Considerations

The

study

subjects

were

explained

the

purpose

of

study

and

assured

privacy.

Confidentiality

and

anonymity

were

maintained

according

to

the

regulations

mandated

by

Research

Ethics

Committee

of

Faculty

of

Medicine

Suez

Canal

University

(no.2357).

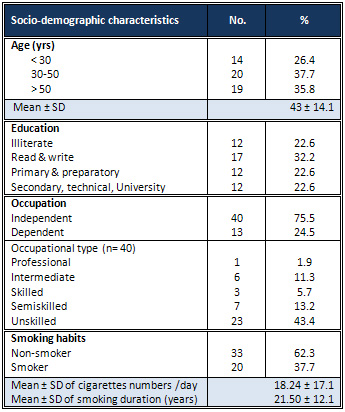

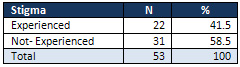

Table

1:

Distribution

of

the

study

group

according

to

Socio-demographic

characteristics

A

total

of

53

patients

consented

to

participate.

The

socio-demographic

profile

of

TB

patients

is

presented

in

Table

1.

The

mean

age

±

SD

was

43

±

14.1

years.

Out

of

the

total

number,

22.6%

were

illiterate

and

77.4%

were

literate.

As

regards

occupation,

69.8%

were

independent

and

30.2%

were

dependent.

There

were

more

male

cases

(77.4

%)

than

female

(22.6%).

Approximately

half

of

the

cases

were

married

(56.6

%)

and

the

majority

had

appropriate

family

income

(64.2%).

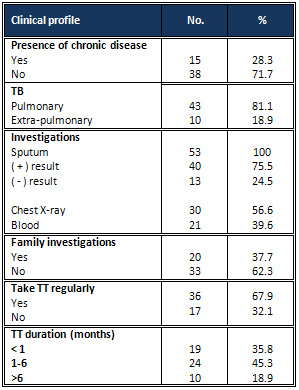

Table

2:

Clinical

profile

of

the

study

population

Table

3:

Prevalence

of

TB

stigma

Table

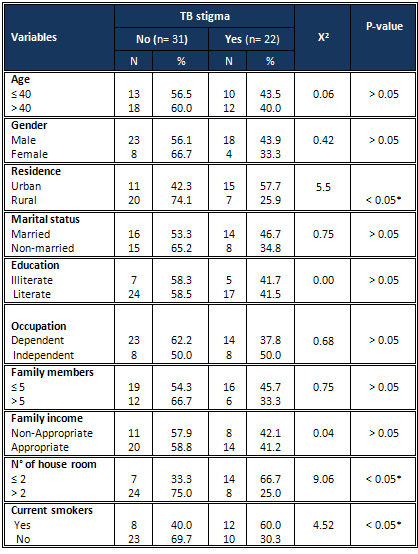

4:

Association

of

risk

factors

and

TB

stigma

As

regards

clinical

profile

of

the

study

population,

81.1%

had

pulmonary

TB

and

75.5%

had

positive

sputum

smear.

The

majority

of

patients

(67.9

%)

take

treatment

regularly

as

presented

in

Table

2.

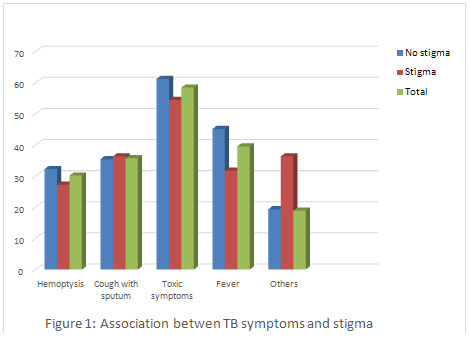

Toxic

symptoms

were

the

most

prevalent

among

TB

patients

(58.5

%)

followed

by

fever

(39.6

%)

and

cough

with

sputum

(35.8

%)

(Figure

1).

The

stigma

prevalence

among

TB

patients

was

found

to

be

41.5%

(Table

3).

Stigma

is

more

prevalent

among

younger

age

groups

(43.5%),

males

43.9%

and

among

married

patients

(46.7%).

There

was

an

immense

stigma

observed

among

urban

residence

(57.7%),

current

smokers

(60.0

%)

and

those

who

had

two

or

less

rooms

in

their

house

(66.7%)

and

this

was

found

to

be

a

statistically

significant

difference

(P<0.05)(

Table

4).

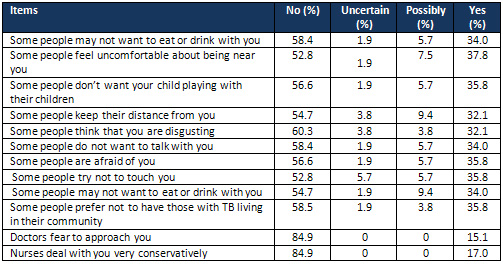

Table

5:

Distribution

of

stigma

score

of

TB

patients

according

to

community

perspectives

Stigma

faced

in

community

by

TB

patients:

About

one

third

of

TB

patients

reported

that

some

people

prefer

not

to

have

those

with

TB

living

in

their

community

and

35.8%

reported

that

some

people

don't

want

their

children

to

play

with

a

TB

patient's

child

(Table

5).

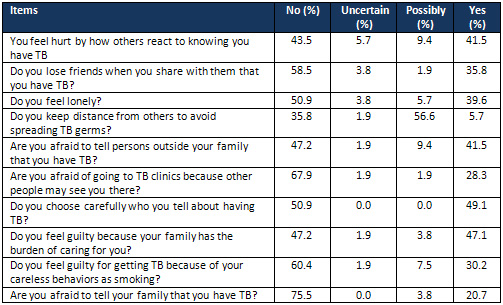

Table

6:

Distribution

of

stigma

score

of

TB

patients

according

to

patient

perspectives

Perceived

Stigma

among

TB

patients:

Out

of

a

total

of

53

patients

41.5%

reported

feeling

hurt

by

how

others

react

to

knowing

that

they

have

TB

and

35.8%

lose

friends

when

they

share

with

them

that

they

have

TB.

Being

afraid

of

going

to

TB

clinics

because

other

people

may

see

them

was

reported

by

28.3%

of

TB

patients.

While

about

half

of

the

patients,

47.1%,

felt

guilty

because

their

family

has

the

burden

of

caring

for

them(Table

6).

Globally,

14.6

million

people

have

active

TB

disease.

Each

year

8.9

million

people

develop

active

TB(24).

Patients

often

isolate

themselves

to

avoid

infecting

others

and

to

avoid

uncomfortable

situations

such

as

being

shunned

or

becoming

the

subject

of

gossip

(25).

Hence,

the

aim

of

this

study

was

to

improve

the

quality

of

life

of

TB

patients

by

identifying

the

magnitude

and

the

burden

of

TB

stigma

on

patients.

Results

of

the

current

study

indicated

that

the

majority

of

the

study

sample

were

men

(77.4

%);

the

same

results

were

supported

by

Aryal(26).

Approximately

half

of

the

cases

were

married

(56.6

%)

and

the

majority

were

literate

and

this

is

in

agreement

with

Abioye

et

al.

(27).

However

this

was

not

supported

in

a

study

in

Bangladesh

where

the

majority

of

patients

had

not

received

any

formal

education

and

this

is

due

to

the

difference

in

culture

and

socioeconomic

characteristics(28).

Our

study

shows

also

that

the

majority

had

appropriate

family

income

(64.2%)

which

matches

the

urban

community

where

the

study

took

place.

Results

showed

that

41.5%

of

the

TB

patients

had

experienced

stigma;

similar

results

were

found

in

Nepal

(63.3%)(26).

The

same

prevalence

was

found

in

a

study

conducted

in

southern

Thailand

by

Rie

AV,

which

shows

that

stigma

is

present

in

patients'

perspective

towards

TB

(29).

Several

studies

suggest

that

health-care

providers

and

at-risk

community

members

perceive

TB

stigma

to

have

a

more

substantial

impact

on

women's

health-care-seeking

behavior

than

on

men's(30).

However

this

disagrees

with

the

study

results

in

which

stigma

was

slightly

more

prevalent

among

men.

This

is

because

most

women

in

our

community

do

not

work

and

do

not

come

in

direct

contact

with

community

members

such

as

men.

In

another

study

work-related

aspects

of

stigma

were

frequently

re-ported,

and

they

were

more

likely

to

be

an

issue

for

men

(28).

In

urban

areas,

there

may

be

more

fears

of

being

discriminated

in

the

work

environment,

or

of

losing

jobs.

This

explains

the

study

results

that

show

that

immense

stigma

observed

among

urban

residence.

Abioye

et

al,

2011

found

that

patients

presenting

with

previous

smoking

history

were

more

likely

to

experience

stigma

in

a

study

in

Lagos,

Nigeria

(27)

and

this

also

can

be

found

in

this

study,

where

there

is

a

statistically

significant

relation

between

stigma

and

smoking.

Abioye

et

al.(2011),

studied

stigma

among

patients

with

pulmonary

tuberculosis

in

Lagos,

Nigeria.

They

found

that

limited

education

and

patients

who

are

in

the

working

age

groups

(20

to

50

years)

had

TB

stigma.

However

according

to

the

current

study

results,

no

statistically

significant

association

could

be

revealed

between

these

two

sociodemographic

determinants.

TB

stigma

has

been

raised

as

a

potential

barrier

to

home-

and

work-based

direct

observational

therapy

(DOT)

(31).

Perceived

TB

stigma

was

also

associated

with

noncompliance

among

Pakistani

patients

on

DOT

(32).

However,

this

study

shows

an

insignificant

relation

between

TB

stigma

and

regularity

of

TB

treatment

and

this

may

have

contributed

to

the

effect

of

TB-related

stigma

and

social

discrimination

on

the

patients

that

forces

them

to

be

compliant

to

drugs

so

that

they

can

avoid

the

stigmatization.

Although

several

survey

instruments

are

in

development

for

measuring

perceived

and

internalized

TB

stigma,

most

research

uses

qualitative

techniques

for

assessing

TB

stigma.

The

use

of

different

measurement

tools

may

explain

why

TB

stigma

is

a

predictor

of

diagnostic

delay

and

treatment

nonadherence

in

some

studies

and

not

in

others(33).

In

this

study

Toxic

symptoms

were

the

most

prevalent

among

TB

patients

(58.5

%)

followed

by

fever

(39.6

%)

and

cough

with

sputum

(35.8

%),

but

the

relation

between

TB

symptoms

and

stigma

were

not

statistically

significant

as

most

stigmatized

TB

patients

usually

do

not

disclose

their

symptoms

as

this

increases

the

state

of

discrimination

in

their

life;

they

want

to

hide

their

symptoms

from

others.

Some

of

the

patients

also

revealed

that

they

go

to

the

DOTS

center

which

is

farther

from

their

home

so

that

nobody

knows

that

they

are

taking

TB

drugs

(26).

In

this

study

35.8%

lose

friends

when

they

share

with

them

that

they

have

TB.

This

is

in

agreement

with

another

study

conducted

in

southern

India

that

showed

that

many

men

felt

inhibited

from

revealing

the

diagnosis

to

friends

(43%)

and

even

to

their

spouse

(16%)

(34).

The

study

results

shows

that

41.5%

reported

feeling

hurt

by

how

others

react

to

knowing

that

they

have

TB

and

35.8%

lose

friends

when

they

share

with

them

that

they

have

TB.

This

was

revealed

in

another

study

in

India

where

most

of

the

patients

said

that

they

have

impaired

self-esteem,

felt

shamed

or

embarrassed,

and

have

felt

less

respect

from

others

in

the

society

(34).

Another

study

conducted

revealed

that

TB

patients

perceive

their

neighbors

and

friends

attitudes

towards

them

as

rather

negative

(35)which

was

in

agreement

with

this

study.

TB

stigma

has

been

raised

as

a

potential

barrier

to

home-

and

work-based

direct

observational

therapy

(DOT)

(31).

Health

education

programs

should

be

conducted

to

reduce

TB

stigma

and

improve

patients'

compliance.

Acknowledgment:To

all

patients

who

agreed

to

participate

in

the

study

and

to

all

members

of

chest

hospitals

in

Suez

Canal

area

for

their

cooperation

and

help.

1.

Facts

about

health

in

African

Subregion,

Fact

sheet

N314

World

Health

Organisation,

2011.

2.

2010/2011tuberculosis

global

fact;

World

Health

Organisation,

http://www.who.int/tb/country/en/index.html,

Nov.

2010.

3.

Global

tuberculosis

control:

a

short

update

to

the

2009

report,

Tech.

Rep.,

World

Health

Organization,

Geneva,

Switzerland,

(WHO/HTM/TB/2009.426),

2009.

4.

Global

tuberculosis

control

2010,

Tech.

Rep.,

World

Health

Organization,

Geneva,

Switzerland,

(WHO/HTM/TB/2010.),

2010.

5.

World

Health

Organization,

Commission

on

Social

Determinants

of

Health.

Closing

the

gap

in

a

generation:

health

equity

through

action

on

the

social

determinants

of

health.

Final

report

of

the

Commission

on

Social

Determinants

of

Health.

Geneva:

WHO;2008.

6.

Heijnders

M,

Van

Der

Meij

S.

The

fight

against

stigma:

an

overview

of

stigma-reduction

strategies

and

interventions.

Psychol

HealthMed

2006;11:353-63.

7.

Link

B,

Phelan

J.

Conceptualizing

stigma.

Annu

Rev

Sociol

2001;27:363-85.

8.

Goffman

E.

Stigma:

notes

on

the

management

of

spoiled

identity.

Garden

City

(NY):

Anchor

Books;

1963.

9.

Smith

R,

Rossetto

K,

Peterson

BL.

A

meta-analysis

of

disclosure

of

one's

HIV-positive

status,

stigma

and

social

support.

AIDS

Care2008;20:1266-75.

10.

Collins

PY,

von

Unger

H,

Armbrister

A.

Church

ladies,

good

girls,

and

locas:

stigma

and

the

intersection

of

gender,

ethnicity,

mental

illness,

and

sexuality

in

relation

to

HIV

risk.

SocSci

Med

2008;67:389-97.

11.

Deacon

H.

Towards

a

sustainable

theory

of

health-related

stigma:

lessons

from

the

HIV/AIDS

literature.

J

Community

ApplSocPsychol

2006;16:418-25.

12.

Courtwright

AM.

Justice,

stigma,

and

the

new

epidemiology

of

health

disparities.

Bioethics

2009;23:90-6.

13.

Major

B,

O'Brien

LT.

The

social

psychology

of

stigma.

Annu

Rev

Psychol

2005;56:393-421.

14.

Parker

R,

Aggleton

P.

HIV

and

AIDS-related

stigma

and

discrimination:

a

conceptual

framework

and

implications

for

action.

SocSci

Med

2003;57:13-2

15.

Whalen

CC.

Failure

of

directly

observed

treatment

for

tuberculosis

in

Africa:

a

call

for

new

approaches.

Clin

Infect

Dis.

2006

Apr

1;42(7):1048-1050.

[PubMed]

16.

Lienhardt

C,

Ogden

JA.

Tuberculosis

control

in

resource-poor

countries:

have

we

reached

the

limits

of

the

universal

paradigm?

Trop

Med

Int

Health.

2004

Jul;9(7):833-841.

[PubMed]

17.

Barker

RD,

Millard

FJ,

Malatsi

J,

et

al.

Traditional

healers,

treatment

delay,

performance

status

and

death

from

TB

in

rural

South

Africa.

Int

J

Tuberc

Lung

Dis.

2006

Jun;10(6):670-675.

[PubMed]

18.

Golub

JE,

Bur

S,

Cronin

WA,

et

al.

Delayed

tuberculosis

diagnosis

and

tuberculosis

transmission.

Int

J

Tuberc

Lung

Dis.

2006

Jan;10(1):24-30.

[PubMed]

19.

Lin

X,

Chongsuvivatwong

V,

Lin

L,

Geater

A,

Lijuan

R.

Dose-response

relationship

between

treatment

delay

of

smear-positive

tuberculosis

patients

and

intra-household

transmission:

a

cross-sectional

study.

Trans

R

Soc

Trop

Med

Hyg.

2008

Aug;102(8):797-804.

[PubMed]

20.

Madebo

T,

Lindtjorn

B.

Delay

in

Treatment

of

Pulmonary

Tuberculosis:

An

Analysis

of

Symptom

Duration

Among

Ethiopian

Patients.

MedGenMed.

1999

Jun

18;E6.

[PubMed]

21.

Storla

DG,

Yimer

S,

Bjune

GA.

A

systematic

review

of

delay

in

the

diagnosis

and

treatment

of

tuberculosis.

BMC

Public

Health.

2008

Jan

14;8(1):15.

[PMC

free

article]

[PubMed]

22.

Weiss

MG,

Ramakrishna

J.

Stigma

interventions

and

research

for

international

health.

Lancet.

2006

Feb

11;367(9509):536-538.

[PubMed]

23.

Baral

SC,

Karki

DK,

Newell

JN.

Causes

of

stigma

and

discrimination

associated

with

tuberculosis

in

Nepal:

a

qualitative

study.

BMC

Public

Health.

2007;7:211.

[PMC

free

article]

[PubMed]

24-

World

Health

Organisation:

Global

Tuberculosis

Control:

surveillance,

planning,

financing.

WHO

report

2006.

Geneva:

World

Health

Organisation;

2006.

25-

Sushil

C

Baral,

Deepak

K

Karki

and

James

N

Newell.

Causes

of

stigma

and

discrimination

associated

with

tuberculosis

in

Nepal:

a

qualitative

study.

BMC

Public

Health

2007,

7:211.

This

article

is

available

from:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/7/211.

26-

Aryal

S,

Badhu

A,

Pandey

S,

Bhandari

A,

Khatiwoda

P,

Khatiwada

P,

et

al.

Stigma

related

to

Tuberculosis

among

patients

attending

DOTS

clinics

of

Dharan

Municipality.

Kathmandu

Univ

Med

J

2012;37(1)48-52.

27-

Abioye

IA,

Omotayo

MO,

Alakija

W.

Socio-demographic

determinants

of

stigma

among

patients

with

pulmonary

tuberculosis

in

Lagos,

Nigeria

African

Health

Sciences

Vol

11

Special

Issue

1

August

2011.

28-

D.

Somma,

B.

E.

Thomas,

F.

Karim,

J.

Kemp,

N.

Arias,

C.

Auer,

G.

D.

Gosoniu,

A.

Abouihia,

M.

G.

Weiss.

Gender

and

socio-cultural

determinants

of

TB-related

stigma

in

Bangladesh,

India,

Malawi

and

Colombia.

INT

J

TUBERC

LUNG

DIS

12(7):856-866

2008.

29-

Rie

AV,

Sengupta

S,

Pungrassami

P,

Balthip

Q,

Choonuan

S,

Kasetjaroen

Y,

et

al.

Measuring

stigma

associated

with

tuberculosis

and

HIV?AIDS

in

southern

Thailand:

exploratory

and

confirmatory

factor

analyses

of

two

new

scales.

Tropical

Medicine

and

International

Health

2008;13(1):21-30.

30-

Thorson

A,

Johansson

E.

Equality

or

equity

in

health

care

access:

a

qualitative

study

of

doctors'

explanations

to

a

longer

doctor's

delay

among

female

TB

patients

in

Vietnam.

Health

Policy.

2004

Apr;68(1):37-46.

31-

Ngamvithayapong

J,

Yanai

H,

Winkvist

A,

Saisorn

S,

Diwan

V.

Feasibility

of

home-based

and

health

centre-based

DOT:

perspectives

of

TB

care

providers

and

clients

in

an

HIV-endemic

area

of

Thailand.

Int

J

Tuberc

Lung

Dis.

2001

Aug;5(8):741-5.

32-

Meulemans

H,

Mortelmans

D,

Liefooghe

R,

Mertens

P,

Zaidi

SA,

Solangi

MF,

et

al.

The

limits

to

patient

compliance

with

directly

observed

therapy

for

tuberculosis:

a

socio-medical

study

in

Pakistan.

Int

J

Health

PlannManag

2002;

17:249-67.

33-

Andrew

Courtwright,

and

Abigail

Norris

Turner.

Tuberculosis

and

Stigmatization:

Pathways

and

Interventions.

Public

Health

Rep.

2010;

125(Suppl

4):

34-42.

34-

Rajeswari

R,

Muniyandi

M,

Balasubramanian

B,

Narayanan

PR.

Perceptions

of

tuberculosis

patients

about

their

physical,

mental

and

social

well-being:

a

field

report

from

south

India.

Social

Science

&

Medicine

2005;

60:1845-53.

35-

Liefooghe

R,

Michiels

N,

Habib

S,

Moran

MB,

Muynck

DA.

Perception

and

social

consequences

of

tuberculosis:

a

focus

group

study

of

tuberculosis

patients

in

Sialkot,

Pakistan.

Social

Science

and

Medicine

1995;41(12):1085-92.

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|