Accurate

estimates

of

virus

mutation

rates

are

important

to

understand

the

evolution

of

the

viruses

and

to

combat

them.

However,

methods

of

estimation

are

varied

and

often

complex.

The

mutation

rate

is

a

critical

parameter

for

understanding

viral

evolution

and

has

important

practical

implications.

For

example,

the

estimate

of

the

mutation

rate

of

HIV-1

demonstrated

that

any

single

mutation

conferring

drug

resistance

should

occur

within

a

single

day

and

that

simultaneous

treatment

with

multiple

drugs

was

therefore

necessary.

(1)

The

viral

mutation

rate

also

plays

a

role

in

the

assessment

of

possible

vaccination

strategies

and

it

has

been

shown

to

influence

the

stability

of

live

attenuated

polio

vaccines.

At

both

the

epidemiological

and

evolutionary

levels,

the

mutation

rate

is

one

of

the

factors

that

can

determine

the

risk

of

emergent

infectious

disease,

i.e.,

pathogens

crossing

the

species

barrier.

Slight

changes

of

the

mutation

rate

can

also

determine

whether

or

not

some

virus

infections

are

cleared

by

the

host

immune

system

and

can

produce

dramatic

differences

in

viral

fitness

and

virulence,

clearly

stressing

the

need

to

have

accurate

estimates.

(1)

Future

mutation

rate

studies

should

fulfil

the

following

criteria:

-

the

number

of

cell

infection

cycles

should

be

as

low

as

possible,

-

the

mutational

target

should

be

large,

-

mutations

should

be

neutral

or

lethal

or

a

correction

should

be

made

for

selection

bias.

Adhering

to

these

criteria

will

help

us

to

obtain

a

clearer

picture

of

virus

mutation

patterns.

(1)

There

have

been

many

laboratory-based

investigations

since

the

emergence

of

the

new

coronaviruses

in

2012,

but

most

of

the

parameters

required

for

establishing

scientifically

the

control

measures

that

will

protect

against

them

have

yet

to

be

determined.

Equally,

the

global

distribution

of

the

viruses

in

their

animal

reservoir

has

yet

to

be

established.

The

approach

to

monitoring

of

virus

mutation

is

to

highlight

particular

questions

that

need

to

be

answered

for

the

purposes

of

preventing

or

treating

these

infections

and

diseases.

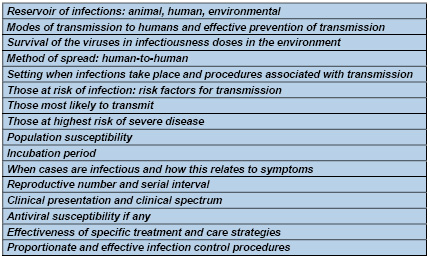

Tables

1-3,

provide

a

summary

of

data

and

investigations

required

for

control

or

mitigation

of

virus

spread.

Table

1:

Information

required

from

investigations

for

control

or

mitigation

of

a

novel

respiratory

virus

affecting

humans

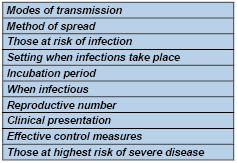

Table

2:

What

parameters

are

involved

in

virus

spread?

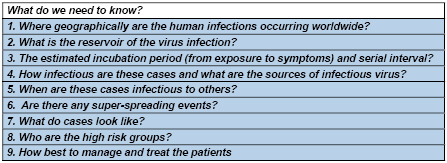

Table

3:

Specific

public

health

questions

regarding

novel

corona

viruses

that

need

to

be

answered

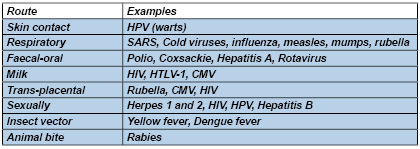

Dealing

with

virus

outbreaks

Viruses

cannot

exist

on

their

own

and

for

survival

they

need

to

spread

to

another

host.

This

is

because

the

original

host

may

either

die

or

eliminate

the

infection.

Some

important

routes

of

viral

transfer

include:

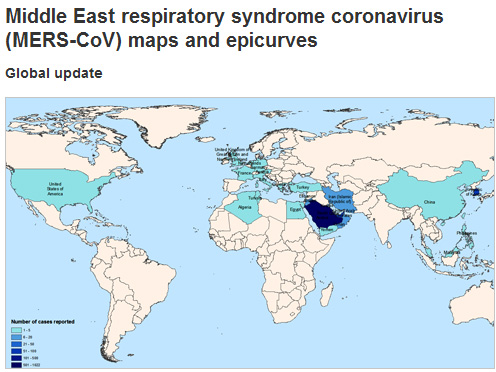

| GLOBAL

AND

REGIONAL

VIRUS

UDATES

|

MERS

Reproduced

with

permission

from:

World

Health

Organization

Coronaviruses

are

a

large

and

diverse

family

of

viruses

that

include

viruses

that

are

known

to

cause

illness

in

humans.Middle

East

Respiratory

Syndrome

coronavirus

(MERS-CoV)

has

never

previously

been

detected

in

humans

or

animals

but

appears

most

closely

related

to

coronaviruses

previously

found

in

bats.

It

is

genetically

distinct

from

the

SARS

coronavirus,

and

appears

to

behave

differently.

The

World

Health

Organization

(WHO)

first

reported

cases

of

Middle

East

Respiratory

syndrome

(MERS)

coronavirus

on

23

September

2012.

While

Saudi

Arabia

has

still

recorded

the

highest

number

of

MERS

deaths,

(over

400)

the

outbreak

continues

in

South

Korea

with

33

deaths

and

183

cases

to

mid

June

2015.

All

cases

have

lived

in

or

travelled

to

the

Middle

East,

or

have

had

close

contact

with

people

who

acquired

the

infection

in

the

Middle

East.

See

map

above

for

current

detail

on

global

and

regional

numbers

of

cases

reported.

MERS

Symptoms

•

Most

people

become

unwell

quickly,

with

fever,

cough,

shortness

of

breath,

leading

to

pneumonia.

•

Other

symptoms

include

muscle

pain,

diarrhoea,

vomiting

and

nausea.

•

There

have

also

been

people

with

mild

symptoms

or

no

symptoms

at

all.

These

people

had

close

contact

with

others

who

were

seriously

ill.

How

MERS

spreads

•

It

appears

to

spread

from

an

infected

person

to

another

person

in

close

contact.

The

virus

does

not

appear

to

spread

easily

from

person-to-person

and

appears

to

spread

only

from

people

who

are

sick.

•

Some

people

in

the

Middle

East

appear

to

have

caught

the

disease

from

infected

camels

and

bats.

How

this

occurred

is

not

well

understood.

People

with

underlying

illnesses

that

make

them

more

vulnerable

to

respiratory

disease

may

be

at

a

higher

risk.

How

it

is

diagnosed

A

laboratory

test

on

fluid

collected

from

the

back

of

the

throat

or

the

lungs

can

diagnose

MERS-CoV.

How

it

is

treated

There

is

no

vaccine

for

MERS-CoV

but

early

and

careful

medical

care

can

save

lives.

Key

facts

•

Middle

East

respiratory

syndrome

(MERS)

is

a

viral

respiratory

disease

caused

by

a

novel

coronavirus

(MERS-CoV)

that

was

first

identified

in

Saudi

Arabia

in

2012.

•

Coronaviruses

are

a

large

family

of

viruses

that

can

cause

diseases

ranging

from

the

common

cold

to

Severe

Acute

Respiratory

Syndrome

(SARS).

•

Typical

MERS

symptoms

include

fever,

cough

and

shortness

of

breath.

Pneumonia

is

common,

but

not

always

present.

Gastrointestinal

symptoms,

including

diarrhoea,

have

also

been

reported.

•

Approximately

36%

of

reported

patients

with

MERS

have

died.

•

Although

the

majority

of

human

cases

of

MERS

have

been

attributed

to

human-to-human

infections,

camels

are

likely

to

be

a

major

reservoir

host

for

MERS-CoV

and

an

animal

source

of

MERS

infection

in

humans.

However,

the

exact

role

of

camels

in

transmission

of

the

virus

and

the

exact

route(s)

of

transmission

are

unknown.

•

The

virus

does

not

seem

to

pass

easily

from

person

to

person

unless

there

is

close

contact,

such

as

occurs

when

providing

unprotected

care

to

a

patient.

Between

1

and

4

June

2015,

the

National

IHR

Focal

Point

for

the

Kingdom

of

Saudi

Arabia

notified

WHO

of

5

additional

cases

of

Middle

East

respiratory

syndrome

coronavirus

(MERS-CoV)

infection,

including

1

death.

Contact

tracing

of

household

and

healthcare

contacts

is

ongoing

for

these

cases.

In

patients

with

suspected

pneumonia

or

pneumonitis

with

a

history

of

recent

residence

or

travel

(in

the

14

days

prior

to

symptom

onset)

in

the

Middle

East*,

or

close

contact

with

confirmed

or

probable

cases,

the

following

is

recommended:

1.

The

patient

should

be

placed

in

a

single

room

if

available

and

standard

and

transmission-based

precautions

implemented

(contact,

droplet

and

airborne),

including

the

use

of

personal

protective

equipment

(PPE).

2.

The

relevant

state/territory

public

health

unit/communicable

diseases

branch

must

be

notified

urgently

of

any

suspected

(and

probable

or

confirmed)

cases

in

order

to

discuss

patient

referral

and

coordinate

management

of

contacts.

Note:

Transiting

through

an

international

airport

(<24hours

duration,

remaining

within

the

airport)

in

the

Middle

East

is

not

considered

to

be

risk

factor

for

infection.

Are

GPs/FPs

at

risk

from

MERS-CoV?

Many

confirmed

cases

have

occurred

in

healthcare-associated

clusters,

and

there

have

been

a

large

number

of

cases

in

healthcare

workers,

but

mainly

in

hospital

settings

as

has

predominantly,

if

not

exclusively,

been

the

case

in

South

Korea.

The

particular

conditions

or

procedures

that

lead

to

transmission

in

hospital

are

not

well

known.

However,

lapses

in

infection

control

were

known

to

have

occurred

for

seven

healthcare

workers

who

acquired

the

infection

from

cases

in

Saudi

Arabia.

Patient

Pre-travel

advice,

travel

restrictions,

periods

of

peak

travel

The

WHO

does

not

currently

recommend

any

restrictions

to

travel

due

to

the

MERS-CoV

outbreak.

Travellers

should

be

aware

of

the

importance

of

personal

hygiene

including

frequent

hand

washing,

avoiding

close

contact

with

animals

and

with

people

who

are

suffering

from

acute

respiratory

infection,

and

should

be

advised

to

seek

medical

attention

as

soon

as

possible

if

they

feel

unwell.

They

should

also

follow

usual

food

hygiene

practices

for

travellers,

including

avoiding

drinking

raw

milk

or

eating

food

that

may

be

contaminated

with

animal

secretions

or

products

unless

they

are

properly

washed,

peeled

or

cooked.

What

are

the

recommended

isolation

and

PPE

recommendations

for

patients

in

hospital?

In

summary,

transmission-based

precautions

for

suspected,

probable

and

confirmed

cases

should

include:

•

Placement

of

confirmed

and

probable

cases

in

a

negative

pressure

room

if

available,

or

in

a

single

room

from

which

the

air

does

not

circulate

to

other

areas

•

Airborne

transmission

precautions,

including

routine

use

of

a

P2

respirator,

disposable

gown,

gloves,

and

eye

protection

when

entering

a

patient

care

area

•

Contact

precautions,

including

close

attention

to

hand

hygiene

•

If

transfer

of

the

confirmed

or

probable

case

outside

the

negative

pressure

room

is

necessary,

asking

the

patient

to

wear

a

surgical

face

mask

while

they

are

being

transferred

and

to

follow

respiratory

hygiene

and

cough

etiquette.

Ebola

Ebola

is

spread

through

contact

with

blood

or

other

body

fluids,

or

tissue

from

infected

people

or

animals.

The

known

strains

vary

dramatically

in

their

fatality

rates.

The

Bundibugyo

strain

fatality

rate

is

up

to

50

percent,

and

it

is

up

to

71

percent

for

the

Sudan

strain,

according

to

WHO.

Less

than

two

months

after

Liberia

was

declared

Ebola-free

by

the

World

Health

Organization,

the

virus

is

back

in

the

country.

Even

when

the

outbreak

diminished

in

Liberia,

neighboring

Guinea

and

Sierra

Leone

have

continued

to

see

20

to

27

cases

a

week

since

late

May

2015,

according

to

the

WHO.

There

have

been

more

than

11,000

total

deaths

from

the

outbreak

since

it

began

in

March

2014.

Ebola

Situation

Report

-

8

July

2015

There

were

30

confirmed

cases

of

Ebola

virus

disease

(EVD)

reported

in

the

week

to

5

July

2015:

18

in

Guinea,

3

in

Liberia,

and

9

in

Sierra

Leone.

Ebola

Situation

Report

-

1

July

2015

There

were

20

confirmed

cases

of

Ebola

virus

disease

(EVD)

reported

in

the

week

to

28

June,

the

same

as

the

previous

week.

Weekly

case

incidence

has

been

between

20

and

27

cases

for

5

consecutive

weeks.

In

Guinea,

12

cases

were

reported

from

3

prefectures:

Boke,

Conakry,

and

Forecariah.

Chikungunya

virus

While

not

fatal,

this

virus

can

have

a

chronic

disabling

effect

and

it

has

spread

rapidly

around

the

globe.

Chikungunya

is

ravaging

the

Caribbean,

having

affected

24

Caribbean

nations

and

possibly

more

than

850,000

people

worldwide,

including

185

Americans

(in

New

Jerseyans).

Chikungunya

virus

is

most

often

spread

to

people

by

Aedes

aegypti

and

Aedes

albopictus

mosquitoes.

These

are

the

same

mosquitoes

that

transmit

dengue

virus.

•

The

only

way

to

prevent

chikungunya

is

to

prevent

mosquito

bites,

such

as

by

using

repellant.

•

Several

vaccines

are

in

the

developmental

stage

but

none

are

in

the

licensing

stage.

•

Generally,

more

South

Jersey

counties

have

a

higher

risk

because

they

have

more

Asian

Tiger

Mosquitoes.

It

is

predicted

that

chikungunya

virus

will

spread

through

rest

of

the

globe

this

year

(2015).

•

Prior

to

2013,

chikungunya

virus

outbreaks

had

been

identified

in

countries

in

Africa,

Asia,

Europe,

and

the

Indian

and

Pacific

Oceans.

•

In

late

2013,

the

first

transmission

of

chikungunya

virus

in

the

Americas

was

identified

in

Caribbean

countries

and

territories.

Local

transmission

means

that

mosquitoes

in

the

area

have

been

infected

with

the

virus

and

are

spreading

it

to

people.

•

Since

then,

local

transmission

has

been

identified

in

44

countries

or

territories

throughout

the

Americas

with

more

than

1.2

million

suspected

cases

reported

to

the

Pan

American

Health

Organization

from

affected

areas.

Symptoms

•

Most

people

infected

with

chikungunya

virus

will

develop

some

symptoms.

•

Symptoms

usually

begin

3-7

days

after

being

bitten

by

an

infected

mosquito.

•

The

most

common

symptoms

are

fever

and

joint

pain.

•

Other

symptoms

may

include

headache,

muscle

pain,

joint

swelling,

or

rash.

•

Chikungunya

disease

does

not

often

result

in

death,

but

the

symptoms

can

be

severe

and

disabling.

•

Most

patients

feel

better

within

a

week.

In

some

people,

the

joint

pain

may

persist

for

months.

•

People

at

risk

for

more

severe

disease

include

newborns

infected

around

the

time

of

birth,

older

adults

(>65

years),

and

people

with

medical

conditions

such

as

high

blood

pressure,

diabetes,

or

heart

disease.

•

Once

a

person

has

been

infected,

he

or

she

is

likely

to

be

protected

from

future

infections.

SARS

Severe

acute

respiratory

syndrome.

No

outbreaks

since

May

2004

China

Avian

Flu

Avian

influenza

A

(H7N9)

is

a

subtype

of

influenza

viruses

that

have

been

detected

in

birds

in

the

past.

This

particular

A

(H7N9)

virus

had

not

previously

been

seen

in

either

animals

or

people

until

it

was

found

in

March

2013

in

China.

However,

since

then,

infections

in

both

humans

and

birds

have

been

observed.

The

disease

is

of

concern

because

most

patients

have

become

severely

ill.

Most

of

the

cases

of

human

infection

with

this

avian

H7N9

virus

have

reported

recent

exposure

to

live

poultry

or

potentially

contaminated

environments,

especially

markets

where

live

birds

have

been

sold.

This

virus

does

not

appear

to

transmit

easily

from

person

to

person,

and

sustained

human-to-human

transmission

has

not

been

reported.

WHO

risk

assessment

of

human

infection

with

avian

influenza

A

(H7N9)

virus

On

23

February

2015

WHO

conducted

a

risk

assessment

in

accordance

with

the

WHO

recommendations

for

rapid

risk

assessment

of

acute

public

health

events

the

summary

can

be

found

below.

Risk

assessment

This

23

February

2015

risk

assessment

was

conducted

in

accordance

with

WHO's

published

recommendations

for

rapid

risk

assessment

of

acute

public

health

events

and

will

be

updated

as

more

information

becomes

available.

Overall,

the

public

health

risk

from

avian

influenza

A(H7N9)

virus

has

not

changed

since

the

assessment

published

on

2

October

20142.

What

is

the

likelihood

that

additional

human

cases

of

infection

with

avian

influenza

A

(H7N9)

viruses

will

occur?

The

understanding

of

the

epidemiology

associated

with

this

virus,

including

the

main

reservoirs

of

the

virus

and

the

extent

of

its

geographic

spread

among

animals,

remains

limited.

However,

it

is

likely

that

most

human

cases

were

exposed

to

the

H7N9

virus

through

contact

with

infected

poultry

or

contaminated

environments,

including

markets

(official

or

illegal)

that

sell

live

poultry.

Changes

to

hygiene

practices

in

live

poultry

markets

have

been

implemented

in

many

provinces

and

municipalities.

Since

the

virus

source

has

not

been

identified

nor

controlled,

and

the

virus

continues

to

be

detected

in

animals

and

environments

in

China,

further

human

cases

are

expected

in

affected

and

possibly

neighbouring

areas.

What

is

the

risk

of

international

spread

of

avian

influenza

A

(H7N9)

viruses

by

travellers?

On

27

and

31

Jan

2015,

Canada

reported

2

cases

of

human

infection

with

avian

influenza

A

(H7N9)

in

travellers

returning

from

China.

These

travellers

had

mild

symptoms

and

only

reported

indirect

contact

with

poultry.

On

12

February

2014,

Malaysia

reported

one

human

case

with

avian

influenza

A

(H7N9)

virus

infection.

The

patient

was

a

Chinese

resident

who

travelled

to

Malaysia

while

sick,

and

was

most

likely

exposed

in

China.

No

further

cases

were

reported

in

Malaysia

linked

to

this

case.

It

is

possible

that

further

similar

cases

will

be

detected

in

other

countries

among

travellers

from

affected

areas,

although

community-level

spread

in

these

other

countries

is

unlikely.

Flu

viruses

During

a

typical

flu

season,

up

to

500,000

people

worldwide

will

die

from

the

illness,

according

to

WHO.

But

occasionally,

when

a

new

flu

strain

emerges,

a

pandemic

results

with

a

faster

spread

of

disease

and,

often,

higher

mortality

rates.

There

are

four

types

of

virus

that

cause

seasonal

flu

in

humans.

Every

year,

drug

developers

try

to

predict

which

strains

are

likely

to

dominate

in

the

next

flu

season

so

as

to

create

an

effective

flu

vaccine.

A

good

understanding

of

the

rate

and

pattern

of

virus

evolution

helps

these

predictions,

as

one

of

the

authors,

Dr.

Ian

Barr,

of

the

World

Health

Organization

(WHO)

Collaborating

Centre

for

Reference

and

Research

on

Influenza

in

Melbourne,

Australia,

explains:

"This

work

represents

another

piece

in

the

complex

puzzle

of

influenza

virus

circulation

and

human

infections

and

provides

insights

that

will

help

develop

better

influenza

vaccines

that

match

strains

circulating

in

the

community."

The

four

viruses

that

cause

seasonal

flu

in

humans

are:

influenza

A

viruses

H3N2

and

H1N1,

and

influenza

B

viruses

Yamagata

and

Victoria.

The

viruses

cause

similar

symptoms

-

for

instance

sudden

fever,

tiredness

and

weakness,

dry

cough,

headache,

chills,

muscle

aches,

sore

throat

-

and

they

evolve

in

similar

ways.

But

what

has

not

been

well

understood

is

their

different

patterns

of

spread

around

the

world

and

what

influences

them.

H1N1

and

B

viruses

persist

locally

between

epidemics.

Marburg

virus

Scientists

identified

Marburg

virus

in

1967,

when

small

outbreaks

occurred

among

lab

workers

in

Germany

who

were

exposed

to

infected

monkeys

imported

from

Uganda.

Marburg

virus

is

similar

to

Ebola

in

that

both

can

cause

hemorrhagic

fever,

meaning

that

infected

people

develop

high

fevers

and

bleeding

throughout

the

body

that

can

lead

to

shock,

organ

failure

and

death.

The

mortality

rate

in

the

first

outbreak

was

25

percent,

but

it

was

more

than

80

percent

in

the

1998-2000

outbreak

in

the

Democratic

Republic

of

Congo,

as

well

as

in

the

2005

outbreak

in

Angola,

according

to

the

World

Health

Organization

(WHO).

Rabies

Although

rabies

vaccines

for

pets,

which

were

introduced

in

the

1920s,

have

helped

make

the

disease

exceedingly

rare

in

the

developed

world,

this

condition

remains

a

serious

problem

in

India

and

parts

of

Africa.

It

destroys

the

brain,

but

there

is

a

vaccine

against

rabies,

and

we

have

antibodies

that

work

against

rabies,

so

if

someone

gets

bitten

by

a

rabid

animal

they

can

be

treated,

If

a

patient

doesn't

get

treatment,

there's

a

100

percent

possibility

they

will

die.

HIV

In

the

modern

world,

the

deadliest

virus

of

all

may

be

HIV.

It

is

still

the

biggest

killer.

An

estimated

36

million

people

have

died

from

HIV

since

the

disease

was

first

recognized

in

the

early

1980s.

Powerful

antiviral

drugs

have

made

it

possible

for

people

to

live

for

years

with

HIV.

But

the

disease

continues

to

devastate

many

low-

and

middle-income

countries,

where

95

percent

of

new

HIV

infections

occur.

Nearly

1

in

every

20

adults

in

Sub-Saharan

Africa

is

HIV-positive,

according

to

WHO.

Dengue

Dengue

virus

first

appeared

in

the

1950s

in

the

Philippines

and

Thailand,

and

has

since

spread

throughout

the

tropical

and

subtropical

regions

of

the

globe.

Up

to

40

percent

of

the

world's

population

now

lives

in

areas

where

dengue

is

endemic,

and

the

disease

-

with

the

mosquitoes

that

carry

it

-

is

likely

to

spread

farther

as

the

world

warms.

Dengue

sickens

50

to

100

million

people

a

year,

according

to

WHO.

Although

the

mortality

rate

for

dengue

fever

is

lower

than

some

other

viruses,

at

2.5

percent,

the

virus

can

cause

an

Ebola-like

disease

called

dengue

hemorrhagic

fever,

and

that

condition

has

a

mortality

rate

of

20

percent

if

left

untreated.

Rotavirus

Two

vaccines

are

now

available

to

protect

children

from

rotavirus,

the

leading

cause

of

severe

diarrheal

illness

among

babies

and

young

children.

The

virus

can

spread

rapidly,

through

what

researchers

call

the

fecal-oral

route

(meaning

that

small

particles

of

feces

end

up

being

consumed).

Although

children

in

the

developed

world

rarely

die

from

rotavirus

infection,

the

disease

is

a

killer

in

the

developing

world,

where

rehydration

treatments

are

not

widely

available.

The

WHO

estimates

that

worldwide,

453,000

children

younger

than

age

5

died

from

rotavirus

infection

in

2008.

But

countries

that

have

introduced

the

vaccine

have

reported

sharp

declines

in

rotavirus

hospitalizations

and

deaths.

The

severity

of

viral

outbreaks

will

largely

depend

on

the

local,

regional

and

global

response

to

them.

Early

vigilance

by

public

health

authorities

and

family

doctors

in

endemic

areas,

particularly,

are

the

greatest

preventive

measure

along

with

hygienic

practices

of

people,

especially

those

living

in

close

proximity

to

animal

or

bird

carriers

and

those

in

hospital

situations.

Global

measures

will

need

to

be

enacted

early

and

up

to

date

information

made

available

to

limit

spread

when

it

does

occur.

Ideally,

as

in

the

case

of

smallpox

which

was

declared

eradicated

in

1980

following

a

global

immunization

campaign

led

by

the

World

Health

Organization,

we

can

start

to

tackle

both

the

initial

outbreaks

and

the

spread

of

the

more

life

threatening

viruses.

This

takes

money

and

global

will.

(1)

Nicoll

A.

Short

communication.

Public

health

investigations

required

for

protecting

the

population

against

novel

coronaviruses

(2)

WHO

Disease

Outbreak

(3)

http://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/symptoms/index.html

(4)

http://www.who.int/csr/don/en/

(5)

Rafael

Sanjuán,

Miguel

R.

Nebot,

Nicola

Chirico,

Louis

M.

Mansky

and

Robert

Belshaw

Viral

Mutation

Rates.

Journal

of

Virology.

July

2010