To

promote

utilization

of

national

medical

research'

recommendations

among

health

policy

makers.

1.

To

identify

enabling

factors

for

utilization

of

national

medical

research'

recommendations

among

MOH

health

policy

makers

in

Jeddah

city,

KSA

2010.

2.

To

determine

barriers

among

MOH

health

policy

makers

toward

utilization

of

national

medical

research'

recommendations

in

Jeddah

city,

KSA

2010

Health

policy-makers

have

been

the

focus

of

studies.

Some

can

involve

health

policy-makers,

for

example

in

mental

health,

being

shown

research

papers

describing

evaluations

of

programmes

and

then

asked

how

useful

they

would

find

such

research.

Others

examine

the

policy-makers'

use

of

research

in

general.(9)

In

Canada

in

1999

one

study

interviewed

25

executive

directors

and

held

a

focus

group

with

a

group

of

other

directors

to

examine

the

use

and

transfer

of

research

in

these

organizations.

A

number

of

central

issues

were

identified

by

the

directors

that

affect

the

contribution

of

research

to

the

delivery

of

their

programs

and

services.

A

conceptual

model

for

developing

'locally-based

research

transfer'

was

subsequently

outlined

that

could

serve

as

the

basis

for

enhanced

research

use

and

research

transfer

in

other

local

area

contexts.(10)

In

Mexico

in

1999

the

results

of

a

descriptive

study

of

the

relationship

between

health

research

and

policy

in

four

vertical

programmes

(AIDS,

cholera,

family

planning,

immunization)

were

reported.

67

researchers

and

policy-makers

from

different

institutions

and

levels

of

responsibility

were

interviewed.

Then

interviewee

responses

looking

for

factors

that

promoted

or

impeded

exchanges

between

researchers

and

policy-makers

were

analyzed.

These

were,

in

turn,

divided

into

emphases

on

content,

actors,

process,

and

context.

Many

of

the

promoting

factors

resembled

findings

from

studies

in

industrialized

countries.

Some

important

differences

across

the

four

programmes,

which

also

distinguish

them

from

industrialized

country

programmes,

included

extent

of

reliance

on

formal

communication

channels,

role

of

the

mass

media

in

building

social

consensus

or

creating

discord,

levels

of

social

consensus,

role

of

foreign

donors,

and

extent

of

support

for

biomedical

versus

social

research.

Various

ways

were

recommended

to

increase

the

impact

of

research

on

health

policy-making

in

Mexico.

Some

of

the

largest

challenges

include

the

fact

that

researchers

are

but

one

of

many

interest

groups,

and

research

but

one

input

among

many

equally

legitimate

elements

to

be

considered

by

policy-makers.

Another

important

challenge

in

Mexico

is

the

relatively

small

role

played

by

the

public

in

policy-making.

Further

democratic

changes

in

Mexico

may

be

the

most

important

incentive

to

increase

the

use

of

research

in

policy-making.(19)

In

Poland

in

1999

a

national

postal

survey

was

conducted

and

supplemented

with

information

collected

during

focus

groups,

semi-structured

interviews

and

through

analysis

of

relevant

policy

documents.

The

main

aim

of

the

described

study

was

to

obtain

data

describing

the

needs,

preferences

and

limitations

of

healthcare

managers

as

information

users,

and

to

identify

environmental

factors

influencing

their

information

behaviour.

The

target

population

included

hospital

chief

executives,

medical

directors,

head

nurses

and

directors

of

the

institutions

responsible

for

health

services

planning

and

purchasing.

Target

institutions

were

drawn

systematically

from

official

lists,

stratified

by

regions

of

the

country

and

hospital

reference

level.

The

interviews

were

conducted

with

primary

care

unit

managers

and

with

Ministry

of

Health

officials.

National

health

strategy

and

directives,

cost-effectiveness

analyses

of

interventions

and

clinical

practice

guidelines

emerged

as

information

of

primary

importance

to

respondents.

The

main

barriers

to

effective

information

behavior

were

found

to

be:

attitudes

towards

research

activity,

lack

of

appropriately

processed

data,

lack

of

skills

enabling

information

seeking

and

appraisal,

inappropriate

format

of

publications,

ineffective

dissemination

of

information

and

absence

of

services

facilitating

access

to

evidence.

The

current

information

environment

of

healthcare

managers,

together

with

their

attitude

towards

information

and

deficiencies

in

information

skills,

appear

to

serve

as

a

barrier

to

evidence-based

practice

in

the

Polish

healthcare

system.(20)

In

2002

,

physicians

from

secondary

and

tertiary

hospitals

in

six

cities

located

in

China,

Thailand,

India,

Egypt

and

Kenya

were

enrolled

in

a

cross-sectional

questionnaire

survey.

The

primary

outcome

measures

were

scores

on

a

Likert

scale

reflecting

stated

likelihood

of

changing

clinical

practice

depending

on

the

source

of

the

research

or

its

publication.

Results

revealed

that

overall,

local

research

and

publications

were

most

likely

to

effect

change

in

clinical

practice,

followed

by

North

American,

European

and

regional

research/publications

respectively,

although

there

were

significant

variations

between

countries.

The

impact

of

local

and

regional

research

would

be

greater

if

the

perceived

research

quality

improved

in

those

settings.

It

was

concluded

that

conducting

high

quality

local

research

is

likely

to

be

an

effective

way

of

getting

research

findings

into

practice

in

developing

countries.(11)

In

2004,

a

survey

of

more

than

550

policy-makers

and

almost

1,900

researchers

in

13

low-

and

middle-income

countries

found

that,

on

average,

a

greater

proportion

of

policy-makers

than

researchers

reported

that

more

resources

should

be

spent

on

health

systems

research

such

as

health

policy,

service

delivery,

financing

and

surveillance

as

the

best

means

of

meeting

the

objectives

of

the

national

health

research

system.(12)

In

2007,

in

Mali,

a

study

of

the

selection

and

updating

of

Mali's

national

essential

medicines

list

was

undertaken

using

qualitative

methods.

In-depth

semi-structured

interviews

and

a

natural

group

discussion

were

held

with

national

policy-makers,

most

specifically

members

of

the

national

commission

that

selects

and

updates

the

country's

list.

The

resulting

text

was

analyzed

using

a

phenomenological

approach.

A

document

analysis

was

also

performed.

Results

showed

several

factors

emerged

from

the

textual

data

that

appear

to

be

influencing

the

utilization

of

health

research

findings

for

these

policy-makers.

These

factors

include:

access

to

information,

relevance

of

the

research,

use

of

research

perceived

as

a

time

consuming

process,

trust

in

the

research,

authority

of

those

who

presented

their

view,

competency

in

research

methods,

priority

of

research

in

the

policy

process,

and

accountability.

It

was

concluded

that

improving

the

transfer

of

research

to

policy

will

require

effort

on

the

part

of

researchers,

policy-makers,

and

third

parties.

This

will

include:

collaboration

between

researchers

and

policy-makers,

increased

production

and

dissemination

of

relevant

and

useful

research,

and

continued

and

improved

technical

support

from

networks

and

multi-national

organizations.

Policymakers

from

developing

countries

will

then

be

better

equipped

to

make

informed

decisions

concerning

their

health

policy

issues.

(5)

Up

to

the

researcher's

knowledge

there

is

no

similar

study

in

KSA,

hence

our

study

will

be

of

great

importance.

3.1

Study

Area:

Jeddah

is

a

Saudi

city

located

in

the

middle

of

the

Eastern

coast

of

the

Red

Sea

known

as

the

'Bride

of

the

Red

Sea'

and

is

considered

the

economic

and

tourism

capital

of

the

country.

Its

population

is

estimated

around

3.4

million

and

it

is

the

second

largest

city

after

Riyadh.(16)

The

study

was

conducted

in

Jeddah

Health

Affairs

involving

all

governmental

and

non

governmental

health

institutions.

Governmental

health

institutions

included

MOH

(Ministry

Of

Health)

hospitals

(n=

9)

plus

PHCC

(

Primary

Health

Care

Center)

sectors

(n=

7)

each

supervisory

sector

includes

6-7

centers

.While

non-governmental

health

institutions

included

all

private

hospitals

(n=31)

and

private

dispensaries

(n=181).

(data

were

obtained

from

Jeddah

Health

Affairs)

3.2

Study

Population:

Target

population

was

constituted

of

those

who

fulfill

definition

of

policy

makers

(individuals

responsible

for

the

development

of

policy

and

supervision

of

execution

of

plans

and

functional

operations).

Governmental:

-

PHCCs:

7

supervisory

sectors.

-

Hospitals:

9

hospitals

Private:

-

In

private

hospitals:

all

general

managers

and

medical

directors

-

In

private

dispensaries:

medical

directors.

3.3

Study

Sample:

•

Sector

supervisors

(n=7)

•

General

managers

&

medical

directors

in

MOH

governmental

hospitals

(9*2)

(n=18)

•

Private

hospitals

(31*2)

(n=62)

•

Medical

directors

in

private

dispensaries

(n=118)

So,

total

was

210

after

adding

5

administrative

directors

at

Jeddah

Health

Affairs

to

the

population

sample.

3.4

Study

Design:

A

cross-sectional

descriptive

study.

3.5

Data

collection

tool:

Validated

questionnaire

published

in

several

studies(15),(17),(18)

for

administrators,

clinicians,

nurses

and

librarians

&

revised

by

epidemiologist

and

public

health

consultant

for

further

adaptation

and

modification

for

policy

makers.

It

was

bilingual

(2

versions

English

&

Arabic)

(see

appendix);

the

English

version

was

translated

into

Arabic

then

it

was

back

translated

to

ensure

lexical

equivalence.

The

questionnaire

included

3

parts:

Socio-demographic

data,

enabling

factors

and

barriers.

The

first

part

was

about

enabling

factors

of

utilization

of

research'

recommendations

(19

questions

plus

8

research

related

questions)

using

a

5

point

Likert

scale

in

which

5=strongly

agree

while

1=strongly

disagree;

the

second

part

was

about

barriers

to

utilization

of

research'

recommendations

(27

questions)

using

the

same

scale

and

the

third

part

included

socio-demographic

data

(7

items).

3.6

Data

collection

technique:

Self

administered

questionnaire

was

used

for

data

collection.

Questionnaires

were

distributed

by

the

researcher

and

3

well

trained

data

collectors

during

regular

day

working

hours

over

a

3

month

period

using

different

methods.

The

first

was

by

visiting

the

hospital

and

meeting

directly

with

the

Director

of

the

hospital

who

filled

out

the

form;

the

second

method

was

to

put

a

file

that

contains

a

form

with

a

letter

from

the

Health

Affairs

Director

and

return

at

a

later

date

to

receive

it

and

the

third

method

was

through

sending

the

form

via

fax

or

e-mail

attached

with

a

letter

after

talking

with

the

director

and

explaining

the

purpose

of

the

research

The

majority

of

data

were

collected

through

direct

meetings.

Regular

meetings

and

contact

between

researcher

and

data

collectors

and

monthly

written

reports

for

progress

of

data

collection

were

done.

All

the

data

were

verified

by

hand

then

were

coded

and

entered

into

a

personal

computer.

3.7

Data

entry

and

analysis:

Data

were

entered

and

analyzed

using

SPSS

version

16.

Categorical

variables

were

presented

as

frequency

and

percentage.

3.8

Pilot

study:

A

pilot

study

was

conducted

in

Makkah

among

10

health

policy

makers

from

different

health

institutions

to

test

the

validity

of

the

questionnaire.

Modifications

were

done

accordingly.

3.9

Ethical

considerations:

•

Written

permission

from

Joint

Program

of

Family

&

Community

Medicine

was

obtained

before

conduction

of

the

research.

•

Written

permission

from

the

concerned

authority

in

MOH

was

obtained

too.

•

Individual

consent

was

considered

as

a

prerequisite

for

data

collection.

It

was

written

on

the

front

page

of

the

questionnaire

that

answering

the

questionnaire

implied

agreement

to

participate

in

the

study).

•

All

information

was

kept

confidential

and

was

not

accessed

except

for

the

purpose

of

scientific

research

3.10

Budget:

The

research

is

self

funded.

The

current

study

aims

at

identifying

enabling

factors

and

determining

barriers

among

health

policy

makers

toward

utilization

of

national

medical

research'

recommendations

in

Jeddah

Governorate.

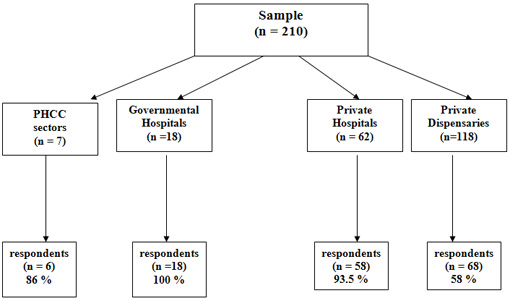

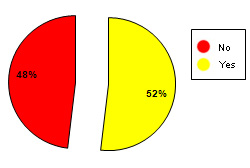

Accordingly

the

respondents

were

210;

response

rate

is

shown

in

Figure

1

and

compensation

of

non

respondents

were

by

medical

directors

of

large

poly

clinics

and

administrative

directors.

Figure

1:

response

rate

of

the

participants

in

the

study

1.

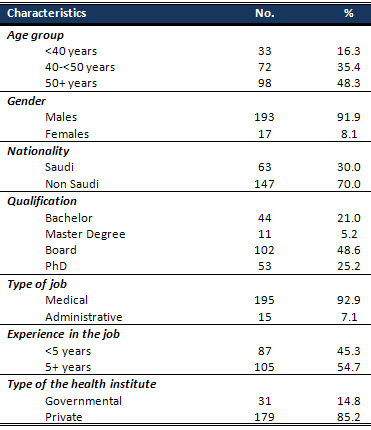

Characteristics

of

the

study

group:

Demographic

characteristics

of

the

study

group

Table

1:

Demographic

characteristics

of

the

study

group

(n=210)

The

table

shows

that

the

majority

of

the

participants

170

(83.7%)

were

in

their

5th

decade

or

above,

and

the

overwhelming

majority

193

(91.9%)

are

males.

The

Saudis

constituted

63

(30%)

of

the

policy

makers

in

the

involved

health

institute,

and

those

who

have

postgraduate

qualifications

amounted

to

be

166

(79%)

who

have

mainly

Board

102

(48.6%)

or

PhD

degrees

53

(25.2%).

The

majority

of

the

participants

have

medical

jobs

195

(92.9)

and

slightly

more

than

one

half

of

them

105

(54.7%)

have

experience

in

their

job

of

five

years

or

more.

The

participants

in

the

governmental

health

institutes

accounted

for

31(14.8%).

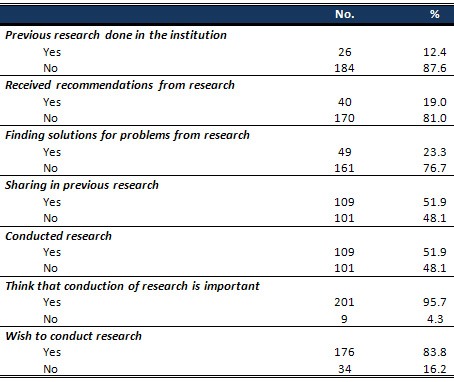

Table

2:

Previous

and

current

participation

in

research

and

opinion

about

conduction

of

research

The

table

shows

that

only

12.4%

of

the

respondents

indicated

that

there

was

previous

research

conducted

in

their

institution

while

19%

addressed

that

they

received

recommendations

from

the

previously

conducted

research.

Moreover,

23.3%

pointed

out

that

they

find

solutions

for

their

problems

in

the

received

recommendations.

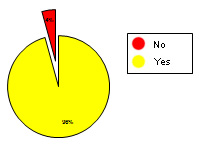

It

was

noted

that

51.9%

of

the

respondents

shared

in

previous

research,

and

an

equal

percentage

reported

that

they

conducted

research

(Figure

2).

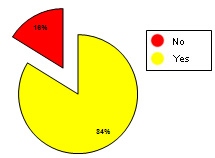

On

the

other

hand,

it

was

remarked

that

although

95.7%

of

the

respondents

believe

that

conduction

of

research

is

important

(Figure

3),

nevertheless,

a

lower

percentage

(83.8%)

of

them

expressed

that

they

wish

to

conduct

research

(Figure

4).

Figure

2:

Previous

research

done

in

the

institution

Figure

3:

Conducted

research

Figure

4:

Think

that

conduction

of

research

is

important

Figure

5:

Wish

to

conduct

research

Click

here

for

Table

3:

Agreement

of

the

respondents

to

the

items

representing

enabling

factors

for

research

The

table

demonstrates

the

agreement

of

the

participants

about

the

statements

representing

the

enabling

factors

for

research.

It

shows

that

the

majority

of

them

agree

about

the

research

quality

being

an

enabling

factor

(90%),

and

an

almost

equal

percentage

(91.1%)

agree

about

concern

in

biomedical

rather

than

social

research,

and

90.9%

agree

about

the

importance

of

specificity,

concreteness

and

cost

effectiveness.

Moreover,

it

was

found

that

95.2%

of

the

respondents

assert

their

agreement

about

the

importance

of

national

support

as

an

enabling

factor,

and

90.5%

pointed

to

the

formal

communications

in

addition

to

91%

who

addressed

political

stability

as

enabling

factors.

On

the

other

hand,

it

was

noted

that

the

great

majority

of

the

participants

(91.5%)

disagree

about

the

assumption

that

utilizing

research

findings

is

time

consuming.

Click

here

for

Table

4:

Agreement

of

the

respondents

to

the

items

representing

barriers

for

research.

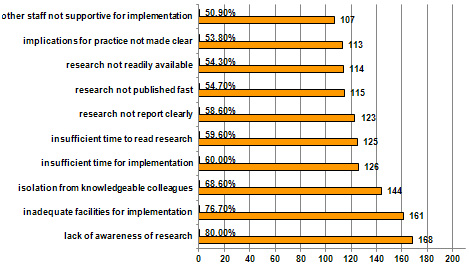

The

table

illustrates

the

response

of

the

participants

to

the

items

representing

barriers

for

conducting

research

arranged

in

descending

order

according

to

the

overall

agreement

for

each

item.

Based

on

this

ranking,

it

was

evident

that

the

top

ten

barriers

included

a

pile

of

situations

pertinent

to

the

staff

working

in

the

institute

such

as

lack

of

their

awareness

to

research,

being

isolated

from

knowledgeable

colleagues

with

whom

to

discuss

the

research

and

lack

of

support

from

other

staff

in

its

implementation.

The

other

pile

of

barriers

are

related

to

the

quality

of

the

research,

where

it

was

found

that

there

is

high

agreement

on

the

ambiguous

reporting

of

the

research,

being

not

readily

available,

vague

implication

on

practice

in

addition

to

late

publication

are

potential

barriers

for

conducting

research.

Moreover,

two

of

the

top

ten

barriers

are

conceptualized

around

the

time

factor,

where

it

was

found

that

60%

of

the

respondents

perceive

that

there

is

not

sufficient

time

on

the

job

to

implement

new

ideas,

in

addition

to

58.6%

who

see

that

there

is

not

sufficient

time

to

read

research.

Finally,

the

factor

which

is

related

to

the

institute

in

general

was

represented

by

the

availability

of

facilities,

where

it

was

found

that

76.7%

of

the

participants

consider

the

inadequate

facilities

in

the

institute

as

a

crucial

barrier

for

implementing

research.

On

the

other

hand,

it

was

remarked

that

the

least

potential

barriers

for

conducting

research

perceived

by

the

respondents

were

related

to

fine

details

of

the

research,

for

example:

difficulty

to

understand

statistical

analyses,

inadequacy

of

the

methodological

design

and

unjustified

conclusions

drawn

from

the

research.

Figure

6:

Agreement

of

the

respondents

to

the

items

representing

top

ten

barriers

for

research

conduction

Making

the

best

use

of

available

research

studies

is

a

priority

goal

in

most

countries,

developed

or

developing,

and

what

was

promising

in

our

study

was

that

the

majority

of

participants

had

a

positive

attitude

toward

research

conduction

although

little

research

was

conducted

by

participants

and

few

of

them

were

useful

in

practice

in

comparison

with

Polish

managers

where

only

15%

of

respondents

thought

that

research

results

had

significant

influence

on

practice

in

health

care,

and

only

3.2%

perceived

developments

in

scientific

knowledge

as

having

an

input

in

their

area

of

decision

making.(20)

Troslte

et

al(19)

looked

for

factors

that

promoted

or

impeded

exchanges

between

researchers

and

policy

makers.

These

were

in

turn

divided

into

emphasis

on

content,

actors,

process,

and

context.

They

finally

recommended

improving

communication

between

researchers

and

policy

makers

via

training

of

both

parties:

assisting

researchers

to

communicate

their

findings

in

an

understandable

and

stimulating

way,

or

synthesizing

policy

makers

on

the

usefulness

of

research

results

as

an

input

to

decision

making.

They

also

recommended

that

research

should

be

evaluated

in

terms

of

its

cost

and

effectiveness

before

being

considered

as

the

basis

for

a

policy

or

program.

However,

this

type

of

evaluation

is

still

underdeveloped

internationally.

(19)

While

in

a

Mali

study

(5)

the

factors

influencing

the

use

of

research

findings

were

Policy-makers'

access

to

information,

relevance

of

research

findings,

perception

that

utilizing

research

findings

is

time-consuming,

policy-makers'

competency

in

research

methods,

trust

policy-makers

place

on

research,

authority

of

those

who

present

their

view,

relative

importance

or

priority

of

research

findings

compared

with

other

sources

of

information

in

the

policy-process

and

uncertainty

of

who

is

responsible

or

accountable

for

accessing,

locating,

and

providing

research

findings

to

address

the

policy-decisions.

In

our

study

the

participants

point

of

views

were

comparable

except

for

the

perception

that

utilizing

research

findings

is

time-consuming,

where

the

majority

disagreed.

On

the

other

hand

two

of

the

top

ten

barriers

are

conceptualized

around

the

time

factor,

where

it

was

found

that

60%

of

the

respondents

perceive

that

there

is

not

sufficient

time

on

the

job

to

implement

new

ideas,

in

addition

to

58.6%

who

see

that

there

is

not

sufficient

time

to

read

research

and

this

could

be

explained

in

the

way

of

utilization

of

research

findings

will

outweigh

the

time

consumed

for

research

conduction

i.e

efficiency

will

mask

real

time

consuming.

Moreover,

it

was

found

that

the

other

top

barriers

included

a

pile

of

situations

pertinent

to

the

staff

working

in

the

institute

such

as

lack

of

their

awareness

to

research,

being

isolated

from

knowledgeable

colleagues

with

whom

to

discuss

the

research

and

lack

of

support

from

other

staff

in

its

implementation.

The

other

pile

of

barriers

are

related

to

the

quality

of

the

research,

where

it

was

found

that

there

is

high

agreement

on

that

the

ambiguous

reporting

of

the

research,

being

not

readily

available,

vague

implications

on

practice,

in

addition

to

late

publication,

are

potential

barriers

for

conducting

research.

Finally,

the

factor

which

is

related

to

the

institute

in

general

was

represented

by

the

availability

of

facilities,

where

it

was

found

that

76.7%

of

the

participants

consider

the

inadequate

facilities

in

the

institute

is

considered

as

a

crucial

barrier

for

implementing

research.

The

current

study

revealed

that

among

the

interviewed

health

policy-makers

there

was

a

gap

between

the

perceived

importance

of

the

research

from

one

side

and

its

conduction

and

utilization

of

its

recommendations

on

the

other

side.

The

reported

barriers

are

mainly

remediable

as

being

attributed

chiefly

to

modifiable

subjective

factors

driven

from

the

lack

of

knowledge

and

experience

about

research

methodology.

In

addition,

the

insufficient

time

perceived

as

a

barrier

reflects

the

vision

of

the

studied

institute

which

are

not

focusing

in

part

of

it

on

conduction

of

research

and

incorporating

it

in

its

plan

and

regular

routine

work.

•

Encouragement

of

conduction

of

research

in

different

health

institutions

through

real

and

pragmatic

support.

•

Incorporate

any

executive

directors,

planners

or

managers

who

are

subjected

to

trainer

course

for

administration

to

be

fortified

by

a

research

methodology

course

•

Deliberate

efforts

should

be

made

to

legislate

provision

of

incentives

for

research

implementation.

(1)

World

Health

Organization.

World

report

on

knowledge

for

better

health

strengthening

health

systems.

Geneva:

World

Health

Organization;

2004.

Available

from

URL

:

http://www.who.int/rpc/meetings/en/world_report_on_knowledge_for_better_health2.pdf

(2)

Hutchinson

AM,

Johnston

L.

Beyond

the

BARRIERS

Scale:

commonly

reported

barriers

to

research

use.

J

Nurs

Adm

2006

Apr;36(4):189-99.

(3)

Gagliardi

AR,

Fraser

N,

Wright

FC,

Lemieux-Charles

L,

Davis

D.

Fostering

knowledge

exchange

between

researchers

and

decision-makers:

exploring

the

effectiveness

of

a

mixed-methods

approach.

Health

Policy

2008

Apr;86(1):53-63.

(4)

Gilson

L,

McIntyre

D.

The

interface

between

research

and

policy:

experience

from

South

Africa.

Soc

Sci

Med

2008

Sep;67(5):748-59.

(5)

Albert

MA,

Fretheim

A,

Maiga

D.

Factors

influencing

the

utilization

of

research

findings

by

health

policy-makers

in

a

developing

country:

the

selection

of

Mali's

essential

medicines.

Health

Res

Policy

Syst

2007;5:2.

(6)

Titler

MG.

Methods

in

translation

science.

Worldviews

Evid

Based

Nurs

2004;1(1):38-48.

(7)

Bostrom

AM,

Kajermo

KN,

Nordstrom

G,

Wallin

L.

Barriers

to

research

utilization

and

research

use

among

registered

nurses

working

in

the

care

of

older

people:

Does

the

BARRIERS

Scale

discriminate

between

research

users

and

non-research

users

on

perceptions

of

barriers?

Implement

Sci

2008;3:24.

(8)

Innvaer

S,

Vist

G,

Trommald

M,

Oxman

A.

Health

policy-makers'

perceptions

of

their

use

of

evidence:

a

systematic

review.

J

Health

Serv

Res

Policy

2002

Oct;7(4):239-44.

(9)

Hanney

SR,

Gonzalez-Block

MA,

Buxton

MJ,

Kogan

M.

The

utilisation

of

health

research

in

policy-making:

concepts,

examples

and

methods

of

assessment.

Health

Res

Policy

Syst

2003

Jan

13;1(1):2.

(10)

Anderson

M,

Cosby

J,

Swan

B,

Moore

H,

Broekhoven

M.

The

use

of

research

in

local

health

service

agencies.

Soc

Sci

Med

1999

Oct;49(8):1007-19.

(11)

World

Health

Organization.

World

report

on

knowledge

for

better

health

strengthening

health

systems.

Geneva:

World

Health

Organization;

2004.

(12)

Page

J,

Heller

RF,

Kinlay

S,

Lim

LL,

Qian

W,

Suping

Z,

et

al.

Attitudes

of

developing

world

physicians

to

where

medical

research

is

performed

and

reported.

BMC

Public

Health

2003

Jan

16;3:6.

(13)

Medical

Dictionary

Online.

Available

from

URL:

http://www.online-medicaldictionary.org/omd.asp?q=POLICY+MAKER

(14)

Pakenham-Walsh

N,

Learning

from

one

another

to

bridge

the

"know-do

gap"

,BMJ

2004;329:1189

(13

November),

doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1189

(15)

Albert

M,

Using

evidence

to

select

essential

medicines,

ESSENTIAL

MEDICINES

MONITOR

WHO,

2009

Nov(2)

(16)

Available

from

http://www.jeddah.gov.sa/English/jeddah/index.php

(17)

Afifi

M

1,

Bener

A,

Research

to

policy

in

the

Arab

world:

lost

in

translation,

Middle

East

Journal

of

Family

Medicine,

2007

Sep

;5(6)

(18)

Funk

SG,

Tornquist

EM,

and

Champagne

MT

,BARRIERS

AND

FACILITATORS

OF

RESEARCH

UTILIZATION

an

Integrative

Review

(19)

Trostle

J,

Brofman

M,

Langer

A.

How

do

researchers

influence

decision

makers?

Case

studies

of

Mexican

policies.

Health

Policy

and

Planning

1999;

14:103-114.

(20)

Niedzwiedzka

BM,

Barriers

to

evidence-based

decision

making

among

Polish

healthcare

managers.

Health

Serv

Manage

Res.

2003

May;16(2):106-15.

Click

here

for

pdf

of

English

and

Arabic

versions

of

Appendix