|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

October 2017 -

Volume 15, Issue 8

|

|

|

View

this issue in pdf formnat - the issue

has been split into two files for downloading

due to its large size: FULLpdf

(12 MB)

Part

1 &

Part

2

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor) |

........................................................

|

|

Original Contribution/Clinical Investigation

Immunity

level to diphtheria in beta thalassemia patients

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93048

[pdf

version]

Abdolreza Sotoodeh Jahromi, Karamatollah Rahmanian,

Abdolali Sapidkar, Hassan Zabetian, Alireza

Yusefi, Farshid Kafilzadeh, Mohammad Kargar,

Marzieh Jamalidoust,

Abdolhossein Madani

Genetic

Variants of Toll Like Receptor-4 in Patients

with Premature Coronary Artery Disease, South

of Iran

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93049

[pdf

version]

Saeideh Erfanian, Mohammad Shojaei, Fatemeh

Mehdizadeh, Abdolreza Sotoodeh Jahromi, Abdolhossein

Madani, Mohammad Hojjat-Farsangi

Comparison

of postoperative bleeding in patients undergoing

coronary artery bypass surgery in two groups

taking aspirin and aspirin plus CLS clopidogrel

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93050

[pdf

version]

Ali Pooria, Hassan Teimouri, Mostafa Cheraghi,

Babak Baharvand Ahmadi, Mehrdad Namdari, Reza

Alipoor

Comparison

of lower uterine segment thickness among nulliparous

pregnant women without uterine scar and pregnant

women with previous cesarean section: ultrasound

study

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93051

[pdf version]

Taravat Fakheri, Irandokht Alimohammadi, Nazanin

Farshchian, Maryam Hematti,

Anisodowleh Nankali, Farahnaz Keshavarzi, Soheil

Saeidiborojeni

Effect

of Environmental and Behavioral Interventions

on Physiological and Behavioral Responses of

Premature Neonates Candidates Admitted for Intravenous

Catheter Insertion in Neonatal Intensive Care

Units

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93052

[pdf

version]

Shohreh Taheri, Maryam Marofi, Anahita Masoumpoor,

Malihe Nasiri

Effect

of 8 weeks Rhythmic aerobic exercise on serum

Resistin and body mass index of overweight and

obese women

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93053

[pdf

version]

Khadijeh Molaei, Ahmad Shahdadi, Reza Delavar

Study

of changes in leptin and body mass composition

with overweight and obesity following 8 weeks

of Aerobic exercise

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93054

[pdf

version]

Khadijeh Molaei, Abbas Salehikia

A reassessment

of factor structure of the Short Form Health

Survey (SF-36): A comparative approach

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93088

[pdf version]

Vida Alizad, Manouchehr Azkhosh, Ali Asgari,

Karyn Gonano

Population and Community Studies

Evaluation

of seizures in pregnant women in Kerman - Iran

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93056

[pdf

version]

Hossein Ali Ebrahimi, Elahe Arabpour, Kaveh

Shafeie, Narges Khanjani

Studying

the relation of quality work life with socio-economic

status and general health among the employees

of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS)

in 2015

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93057

[pdf version]

Hossein Dargahi, Samereh Yaghobian, Seyedeh

Hoda Mousavi, Majid Shekari Darbandi, Soheil

Mokhtari, Mohsen Mohammadi, Seyede Fateme Hosseini

Factors

that encourage early marriage and motherhood

from the perspective of Iranian adolescent mothers:

a qualitative study

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93058

[pdf

version]

Maasoumeh Mangeli, Masoud Rayyani, Mohammad

Ali Cheraghi, Batool Tirgari

The

Effectiveness of Cognitive-Existential Group

Therapy on Reducing Existential Anxiety in the

Elderly

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93059

[pdf

version]

Somayeh Barekati, Bahman Bahmani, Maede Naghiyaaee,

Mahgam Afrasiabi, Roya Marsa

Post-mortem

Distribution of Morphine in Cadavers Body Fluids

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93060

[pdf

version]

Ramin Elmi, Mitra Akbari, Jaber Gharehdaghi,

Ardeshir Sheikhazadi, Saeed Padidar, Shirin

Elmi

Application

of Social Networks to Support Students' Language

Learning Skills in Blended Approach

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93061

[pdf

version]

Fatemeh Jafarkhani, Zahra Jamebozorg, Maryam

Brahman

The

Relationship between Chronic Pain and Obesity:

The Mediating Role of Anxiety

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93062

[pdf

version]

Leila Shateri, Hamid Shamsipour, Zahra Hoshyari,

Elnaz Mousavi, Leila Saleck, Faezeh Ojagh

Implementation

status of moral codes among nurses

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93063

[pdf

version]

Maryam Ban, Hojat Zareh Houshyari Khah, Marzieh

Ghassemi, Sajedeh Mousaviasl, Mohammad Khavasi,

Narjes Asadi, Mohammad Amin Harizavi, Saeedeh

Elhami

The comparison

of quality of life, self-efficacy and resiliency

in infertile and fertile women

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93064

[pdf version]

Mahya Shamsi Sani, Mohammadreza Tamannaeifar

Brain MRI Findings in Children (2-4 years old)

with Autism

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93055

[pdf

version]

Mohammad Hasan Mohammadi, Farah Ashraf Zadeh,

Javad Akhondian, Maryam Hojjati,

Mehdi Momennezhad

Reviews

TECTA gene function and hearing: a review

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93065

[pdf version]

Morteza Hashemzadeh-Chaleshtori, Fahimeh Moradi,

Raziyeh Karami-Eshkaftaki,

Samira Asgharzade

Mandibular

canal & its incisive branch: A CBCT study

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93066

[pdf

version]

Sina Haghanifar, Ehsan Moudi, Ali Bijani, Somayyehsadat

Lavasani, Ahmadreza Lameh

The

role of Astronomy education in daily life

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93067

[pdf

version]

Ashrafoalsadat Shekarbaghani

Human brain

functional connectivity in resting-state fMRI

data across the range of weeks

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93068

[pdf version]

Nasrin Borumandnia, Hamid Alavi Majd, Farid

Zayeri, Ahmad Reza Baghestani,

Mohammad Tabatabaee, Fariborz Faegh

International Health Affairs

A

brief review of the components of national strategies

for suicide prevention suggested by the World

Health Organization

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93069

[pdf

version]

Mohsen Rezaeian

Education and Training

Evaluating

the Process of Recruiting Faculty Members in

Universities and Higher Education and Research

Institutes Affiliated to Ministry of Health

and Medical Education in Iran

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93070

[pdf

version]

Abdolreza Gilavand

Comparison

of spiritual well-being and social health among

the students attending group and individual

religious rites

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93071

[pdf

version]

Masoud Nikfarjam, Saeid Heidari-Soureshjani,

Abolfazl Khoshdel, Parisa Asmand, Forouzan Ganji

A

Comparative Study of Motivation for Major Choices

between Nursing and Midwifery Students at Bushehr

University of Medical Sciences

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93072

[pdf

version]

Farzaneh Norouzi, Shahnaz Pouladi, Razieh Bagherzadeh

Clinical Research and Methods

Barriers

to the management of ventilator-associated pneumonia:

A qualitative study of critical care nurses'

experiences

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93073

[pdf version]

Fereshteh Rashnou, Tahereh Toulabi, Shirin Hasanvand,

Mohammad Javad Tarrahi

Clinical

Risk Index for Neonates II score for the prediction

of mortality risk in premature neonates with

very low birth weight

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93074

[pdf

version]

Azadeh Jafrasteh, Parastoo Baharvand, Fatemeh

Karami

Effect

of pre-colporrhaphic physiotherapy on the outcomes

of women with pelvic organ prolapse

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93075

[pdf

version]

Mahnaz Yavangi, Tahereh Mahmoodvand, Saeid Heidari-Soureshjani

The

effect of Hypertonic Dextrose injection on the

control of pains associated with knee osteoarthritis

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93076

[pdf

version]

Mahshid Ghasemi, Faranak Behnaz, Mohammadreza

Minator Sajjadi, Reza Zandi,

Masoud Hashemi

Evaluation

of Psycho-Social Factors Influential on Emotional

Divorce among Attendants to Social Emergency

Services

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93077

[pdf

version]

Farangis Soltanian

Models and Systems of Health Care

Organizational

Justice and Trust Perceptions: A Comparison

of Nurses in public and private hospitals

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93078

[pdf

version]

Mahboobeh Rajabi, Zahra Esmaeli Abdar, Leila

Agoush

Case series and Case reports

Evaluation

of Blood Levels of Leptin Hormone Before and

After the Treatment with Metformin

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93079

[pdf

version]

Elham Jafarpour

Etiology,

Epidemiologic Characteristics and Clinical Pattern

of Children with Febrile Convulsion Admitted

to Hospitals of Germi and Parsabad towns in

2016

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93080

[pdf

version]

Mehri SeyedJavadi, Roghayeh Naseri, Shohreh

Moshfeghi, Irandokht Allahyari, Vahid Izadi,

Raheleh Mohammadi,

Faculty development

The

comparison of the effect of two different teaching

methods of role-playing and video feedback on

learning Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93081

[pdf

version]

Yasamin Hacham Bachari, Leila Fahkarzadeh, Abdol

Ali Shariati

Office based family medicine

Effectiveness

of Group Counseling With Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy Approach on Couples' Marital Adjustment

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93082

[pdf

version]

Arash Ziapour, Fatmeh Mahmoodi, Fatemeh Dehghan,

Seyed Mehdi Hoseini Mehdi Abadi,

Edris Azami, Mohsen Rezaei

|

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| October 2017 -

Volume 15, Issue 8 |

|

|

Factors that encourage

early marriage and motherhood from the perspective

of Iranian adolescent mothers: a qualitative

study

Maasoumeh Mangeli (1)

Masoud Rayyani (2)

Mohammad Ali Cheraghi (3)

Batool Tirgari (4)

(1) PhD

candidate in nursing, Nursing Research Center,

Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman,

Iran

(2) Assistant Professor, Nursing Research Center,

Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman,

Iran

(3) Associate Professor, School of Nursing and

Midwifery; Tehran University of Medical Sciences,

Tehran, Iran

(4) Assistant Professor, Kerman Neuroscience

Research Center and Neuropharmacology Institute,

Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman,

Iran

Correspondence:

Masoud

Rayyani

School of Nursing and Midwifery

Kerman University of Medical Sciences,

Kerman, Iran

Tel: 00983431325219; Mobile: 00989131982924;

Fax: 00983431325218

Email:

M_rayani@kmu.ac.ir

|

Abstract

Background: Early

marriage and motherhood is one of the

most important health challenges in developing

countries and affects mothers, children,

families and communities, thus their causes

and predisposing factors must be explored.

The aim of this study was to explore the

factors that encourage early marriage

and motherhood in Iranian culture.

Methods:

Inductive Conventional Content Analysis

approach was used in this qualitative

study. Face to face in-depth semi-structured

interview were conducted with 16 Iranian

adolescent mothers in the Kerman province

of Iran. Data collection continued until

acquiring data saturation and MAXQDA software

was used for analysis of the data.

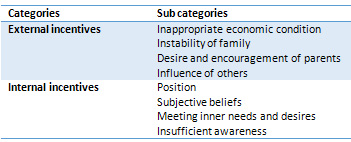

Results: Two

main categories (external incentives and

internal incentives) and 8 sub-categories

(inappropriate economic condition, instability

of family, desire and encouragement of

parents, copying others, position (status),

subjective beliefs, meeting inner needs

and desires, insufficient awareness) were

extracted from the data.

Conclusion: Various

factors (personal, social, economic, cultural,

spiritual and technological) encourage

adolescents to early marriage and motherhood.

Understanding of these factors can help

health care providers, who work in the

field of mother and child health, to provide

appropriate assessment and interventions

for improvement of the health of this

group of society.

Key words:

Adolescent Mothers, Marriage, Encourage,

Iran, Qualitative

|

Marriage is one of the most important life

events and is necessary for development of societies(1),

but early marriage will be followed by unpleasant

feelings if participants are not being prepared

to take on new responsibilities(2). Early marriage

which includes any legal or illegal marriage

under the age of 18 (3, 4) is among the important

challenges of the world, and it is estimated

to reach 150 million cases by 2030 (5). Early

marriages exist in many countries, especially

developing countries, but most cases (46%) are

related to South Asian countries(3). Early marriage

and motherhood in Iranian culture has long been

approved and the highest number of marriages

has been seen among 15-19 year old girls(6,

7).

Although adulthood is one of the requirements

for accepting mother’s role, an increasing

number of adolescent mothers are among serious

challenges of many countries(8). According to

the World Health Organization, more than 16

million adolescents become mothers each year(9).

Such number is the lowest in South Korea and

it is the highest in sub-Sahara Africa. Among

1,000 Iranian adolescent girls, 27 become mothers(10).

Adolescent mothers, who must simultaneously

go through two developmental crises (motherhood

and adolescence), are not physically and emotionally

ready to take the roles of mother, wife and

their consequent responsibilities, and they

are not able to overcome social and psychological

challenges (11, 12).

Early motherhood has many consequences for

girls, society, and the environment(8). It also

causes financial problems for children’s

future and reduced social support(13). Child

abuse, behavioral problems, shock, low self-esteem,

depression and role conflict are seen in adolescent

mothers(11). Low accountability, emotional fluctuations,

lack of knowledge and experience, less desire

to engage emotionally with the baby and breastfeeding,

lack of attention to health and safety issues,

the influence of peers and the probability of

high risk behaviors during adolescence; highlight

the importance of health care providers’

role in dealing with such clients(14). In developed

countries, there are several strategies for

protect girls from early motherhood. In developed

countries early motherhood is considered specially

along with cardiovascular disease, cancer, and

mental disorders (15), and it is studied by

gynecologists, obstetricians, pediatricians,

psychologists, sociologists and family physicians(16).

Studies have indicated that many factors are

effective on early marriage and motherhood including;

economic factors (poverty, unemployment) (4,

6, 17, 18), social factors (gender discrimination,

school dropout, social norms, mass media, migration

from rural to urban areas, the influence of

peers)(4, 15, 17, 19-21), cultural and religious

factors (prevention from unrestrained sexual

promiscuity, religious and cultural incentives,

ethnicity and race) (19, 22), safety factors

(war, rape, kidnapping)(3, 17, 22), psychological

factors (low self-esteem, mental health problems,

anti-social behavior, sense of emotional maturity)(19,

23, 24), political and legal factors (the national

laws for marriage and sexual relations, legal

gap)(23, 25), organizational factors (views

of health care givers and access to services)(23),

family factors (breakdown of family structures,

the absence of father, family values, social

and psychological problems of parents, parents

demand)(3, 24), and individual factors (inability

to continue education, love, desire to have

children, sense of empowerment)(19).

Since, the provision of desirable healthcare

services to adolescent mothers requires understanding

of factors that encourage marriage and pregnancy

through qualitative studies, this study was

conducted to determine the factors that encourage

early marriage and motherhood from the perspective

of Iranian adolescent mothers. Findings of this

study can lead healthcare teams to make proper

decisions.

Design: This qualitative study was conducted

through inductive conventional content analysis.

Content analysis is a suitable method for obtaining

valid and reliable results from textual data

in order to create knowledge, new ideas, facts

and a practical guide for performance, which

extract concepts or descriptive themes from

the phenomenon. This approach is recommended

when there is not enough knowledge about the

phenomenon or if this knowledge is fragmented

(26).

Participants & Setting: This study

was conducted in 2016 in Kerman province of

Iran. Kerman is located in the south east of

Iran, and has a high rate of adolescent mothers.

A total of 16 adolescent mothers who met the

inclusion criteria (having maximum of 19 years

of age at the time of first birth, have a child

or children up to 2 years of age, marriage of

legal form, being able to speak Persian, being

willing to share personal experiences and good

cooperation with the researcher) participated

in this study. Participants were selected purposefully

with maximum variation in age, child’s

age, place of residence (urban or rural), financial

situation (Table 1).

Data collection: Data were collected

through in-depth semi-structured interviews

conducted by first author (PhD candidate in

nursing).The interviews were focused on the

perspectives of the participants. Adolescents

were asked to explain factors that have encouraged

them towards early marriage and motherhood.

Interviews began with a general question and

progressed to specific questions. Time and place

of the interviews were set with the agreement

of the participants which were mainly at home.

Interviews lasted for 45 to 60 minutes and during

a 5-month period from March to August 2016.

Entire interviews were recorded and transferred

into audio files to be entered in the computer.

Data collection continues until data saturation,

when no new information was obtained from the

interviews

Data Analysis: Analysis of the data

was done by using the inductive conventional

content analysis approach (Graneheim & Lundeman)(26).

Predetermined categories were not used and categories

emerge from the data. First audio files of interviews

were listened to and recorded interviews were

immediately transcribed verbatim and then read

several times to gain a general impression.

The resulting text from the interviews was read

line by line and broken down into meaning units

(words or sentence or paragraphs), which were

then condensed, abstracted, coded, and labeled.

Then, the codes were re-read in order to be

arranged into categories and sub-categories

based on their similarities and differences.

The first author performed data coding and all

co-authors supervised the coding process. If

there was a disagreement over the coding, the

authors discussed and negotiated the codes until

they achieved agreement. Data analysis was done

continuously and simultaneously with data collection

and the data and the generated codes were constantly

compared. MAXQDA10 software was used also.

Trustworthiness: In this study, credibility

increased through prolonged engagement with

the researcher, spending sufficient time for

data collection and analysis, favorite communication

with participants, member check and peer check.

To increase dependability, the baseline review

of literature was limited at the beginning of

the study and the opinion of an expert (outside

the research team) was used. For confirmability,

the research process was accurately recorded

to make the follow-up possible. To ensure transferability,

results of the study were checked with numbers

of similar samples who were not among the participants.

Ethical considerations: The Kerman University

of Medical Sciences Human Research Committee

approved this study (ethics approval number:

IR.KMU.REC.1394.591). Purpose of the study,

how to publish results, and possible risks,

dangers and benefits were explained to the participants.

Participant anonymity, privacy and confidentiality

were maintained. Interviews were conducted in

a private and non-threatening environment and

audio files were be kept anonymously in a secure

place. Participants were ensured that their

responses would remain confidential. Participants

were also informed that participation in the

study was voluntary and they could withdraw

at any time. Written informed consent for participation

in the study and recording of the interview

was obtained. During the data collection, the

first author was ready to provide help and support;

if necessary.

Click

here

for

Table1:

Demographic

characteristics

of

participants

In

total,

factors

that

encouraged

early

marriage

and

motherhood

were

classified

into

two

main

categories

and

eight

sub-categories

(Table

2).

Table

2:

Main

categories

and

sub

categories

of

factors

that

encourage

early

marriage

and

motherhood

1.

External

incentives

External

motivations

related

to

family,

life

position

and

community

had

caused

adolescents

to

get

married

and

become

mothers.

1-1:

Inappropriate

economic

conditions:

The

financial

problem

was

one

of

unpleasant

situations

for

early

marriage.

Some

adolescents

were

getting

married

to

improve

economic

conditions

for

themselves

and

their

families

(Table

3.

Quotation

1).

1-2:

Instability

of

the

family:

Family

breakdown,

divorce

or

death

of

parents

had

caused

adolescents

to

get

married,

and

separation

from

family

created

a

better

position

for

them

(Table

3.

Quotation

2).

Trying

to

resolve

family

disputes

and

helping

strengthen

families

were

also

among

reasons

stated

by

adolescents

for

pregnancy

(Table

3.

Quotation

3).

1-3:

Desire

and

encouragement

of

parents:

Early

marriage

of

some

adolescents

was

due

to

urging

of

their

parents.

Financial

problems,

social

norms,

cultural

and

religious

issues

or

their

personal

attitude

were

encouraged

by

parents

to

this

desire

(Table

3.

Quotation

4,

5).

1-4:

Copying

from

others:

Excessive

interest

in

friendship

and

the

need

to

be

approved

by

friends

affected

the

decision

of

adolescents

on

marriage

(Table

3.

Quotation

6).

Early

marriage

of

sister

or

brother

had

also

encouraged

adolescents

to

get

married

in

order

to

be

similar

to

other

family

members

(Table

3.

Quotation7).

2

-

Internal

incentives

Some

factors

that

encouraged

early

marriage

were

related

to

adolescents

‘desires’,

and

were

originated

from

their

beliefs.

2-1:

Position:

Some

adolescents

were

married

in

order

not

to

lose

such

an

opportunity.

Adequate

understanding

of

the

suitor

and

detecting

ideal

features

in

him,

were

some

of

the

reasons

of

early

marriage

(Table

3.

Quotation

8).

Some

of

the

adolescents

thought

that,

protection

of

marital

relations

depended

on

childbirth.

Therefore

they

had

decided

to

get

pregnant

(Table

3.

Quotation

9).

2-2:

Subjective

beliefs

that

encourage

the

marriage

&

motherhood:

Some

adolescents

selected

marriage

because

of

their

subjective

thoughts

and

beliefs.

Some

considered

marriage

as

God’s

will

and

divine

destiny

and

were

not

opposed

to

it

(Table

3.

Quotation

10).

The

belief

“the

situation

will

get

better

and

more

comfortable

by

childbirth”,

had

caused

adolescents

to

get

pregnant

(Table3.

Quotation

11).

Early

puberty

and

gaining

some

abilities

had

caused

adolescents

to

imagine

that

they

were

ready

to

get

married

(Table

3.

Quotation

12).

Facing

cultural

beliefs

in

consequences

of

contraception

had

encouraged

adolescents

to

get

pregnant

and

act

based

on

their

mentalities

(Table

3.

Quotation

13).

2-3:

Meeting

inner

needs

and

desires:

Feelings

of

loneliness

and

desires,

love,

respect,

and

independence

had

encouraged

some

adolescents

to

be

married.

Adolescents

wanted

independence

and

freedom

in

decision

making

and

expected

to

be

addressed

as

an

influential

person.

They

were

tired

of

parental

interferences

and

were

married

for

love,

soul-mate,

and

value

acquirement

(Table

3.

Quotation

14).

Most

participants

expressed

that

they

wanted

a

child

to

get

rid

of

loneliness.

Some

adolescents

had

become

lonely

after

separating

from

previous

dependencies

such

as;

family,

friend,

school,

etc…

(Table

3.

Quotation

15).

Also

having

old

parents

who

had

not

been

able

to

be

friendly

with

their

children,

had

encouraged

adolescent

girls

to

get

pregnant

and

close

the

age

gap

between

themselves

and

their

children

(Table

3.

Quotation

16).

Love

and

desire

towards

baby,

and

satisfying

the

sense

of

possession

which

is

one

of

the

characteristics

of

adolescence

were

reflected

in

the

statements

of

participants

(Table

3.

Quotation

17).

2-4:

Insufficient

awareness:

Some

of

the

adolescents

thought

marriage

was

simple

and

viewed

it

as

a

child

play

as

they

lacked

sufficient

knowledge

about

it,

its

meaning

and

philosophy.

They

were

assuming

the

marriage

only

by

its

apparent

applications

and

had

not

thought

about

it

seriously

(Table

3.

Quotation

18).

Some

of

them

were

presuming

childbirth

as

a

simple

process,

and

were

unaware

of

the

possible

difficulties

of

pregnancy

and

childbirth

(Table

3.

Quotation

19).

Not

having

enough

information

about

the

possible

mechanisms

of

pregnancy,

unfamiliar

with

contraceptive

methods,

and

they

referred

to

their

imperfect

knowledge

in

this

field

as

the

cause

of

early

pregnancy

(Table

3.

Quotation

20).

Table

3:

Quotations

of

Participants

Quotation

1

“I

saw

my

dad

and

my

mom

were

struggling

financially.

They

had

difficult

to

covering

our

costs,

so

I

was

helping

them

as

much

as

I

could,

I

was

working,

then

I

thought

that

it

was

better

to

get

married.

I

wanted

to

leave

the

home

earlier

so

I

could

help

my

parents”.p4

Quotation

2

“I

was

nine

years

old

when

my

parents

got

divorced

...

my

mother

married

another

man.

I

had

a

lot

of

problems

with

my

stepfather

and

half-sisters

and

brothers.

I

could

not

accept

my

stepfather

as

my

father.P6

Quotation

3

“My

mother-in-law

was

angry

with

my

mother.

My

mother

said:

if

you

have

children,

the

hatred

and

resentment

between

the

two

families

will

be

resolved”.p7

Quotation

4

“When

my

sisters

got

married,

my

father

said

to

me:

if

a

good

suitor

comes

for

you,

you

have

to

accept

him.

My

parents

were

satisfied

with

him

so

I

accepted

to

get

married”

p15

Quotation

5

“A

few

months

after

our

marriage

my

husband

said:

we

must

have

a

baby

as

I

could

not

resist

my

parents’

insistence

anymore.

I

did

not

want

to

become

pregnant

too

soon,

but

my

husband’s

parents

forced

us”.p3

Quotation

6

“I

saw

my

friends

who

were

married

and

also

studying.

They

were

satisfied.

I

thought

I

could

do

the

same

thing.

I

was

always

like

them;

we

were

buying

the

same

clothes,

and

having

fun

together.

I

did

not

want

to

fall

behind

them.

When

the

first

suitor

came,

I

got

married”.

P5

Quotation

7

“Only

one

of

my

sisters

married

when

she

was

20

and

my

other

sisters

and

brothers

got

married

at

17

or

18

years.

In

our

family,

my

siblings

get

married

at

early

age”.p12

Quotation

8

“I

knew

him

very

well.

They

were

very

nice

people...

he

met

my

criteria.

I

was

going

to

school

that

time,

but

I

thought,

if

I

got

married

I

would

be

better

off

because

my

husband

had

a

good

condition.

I

did

not

want

to

miss

the

chance”p10

Quotation

9

“Three

months

had

passed

since

our

marriage

but

I

was

not

pregnant

yet.

I

told

my

husband:

if

I

do

not

get

pregnant

we

would

get

divorced,

so

you

could

marry

again

and

have

kids

...

I

was

really

scared”.p4

Quotation

10

“It

was

God’s

will

that

we

got

married.

It

just

happened.

I

said

nothing,

and

did

not

oppose

it.

I

let

it

happen”.p1

Quotation

11

“My

mother-in-law

said;

“if

you

have

a

baby,

God

will

sort

everything

out

and

if

there

is

a

problem

it

will

be

solved”.p6

Quotation

12

“I

was

fatter

than

my

peers.

I

became

menstruate

very

soon.

I

had

to

cook,

clean

and

do

housework.

I

had

learned

lots

of

things.

My

attitude

was

like

older

women,

and

I

understood

more

than

my

age.

I

thought,

I

knew

how

to

deal

with

husband

and

his

family.

My

general

knowledge

was

so

high

that

older

people

were

consulting

with

me.”p8

Quotation

13

“My

mother-in-law

said;

“if

you

use

contraceptive

pills,

you

may

never

get

pregnant.

Contraception

is

not

good”.

She

said:

if

I

use

contraceptive

pills,

my

ovaries

may

stop

working

forever

and

I

could

never

have

children”.p14

Quotation

14

“Before

I

was

married,

my

parents

decided

for

me.

I

wanted

to

be

independent

and

I

didn’t

like

people

interfere

in

my

business.

I

wanted

to

get

married

as

soon

as

possible,

perhaps

I

would

have

more

freedom.

I

wanted

to

get

married

to

somebody

that

I

love.

Someone

that

we

could

make

plan

for

our

life

together,

and

ask

me

what

I

like.

We

would

have

fun

together

and

be

together”.p3

Quotation

15

“As

I

have

no

sister

or

brother,

father,

mother

or

friends,

I

decided

to

get

pregnant,

no

one

was

beside

me”.p11

Quotation

16

“I

like

to

have

a

grown

up

child

when

I

am

still

young,

because

my

parents

were

old

and

they

could

not

understand

me.

I

wished

my

parents

were

younger

so

we

could

talk

with

each

other.

I

liked

to

get

married

early

so

my

children

wouldn’t

feel

the

same”.p2

Quotation

17

“I

like

kids

very

much.

I

wanted

to

have

children.

When

I

saw

other

people’s

children,

I

wanted

to

have

a

baby

too”.

P8.

Quotation

18

“My

dad

said:

do

you

want

to

get

married?

Yeah,

I

like

it

very

much

I

replied.

I

did

not

know

what

marriage

means.

I

thought

it

was

very

good,

I

could

put

makeup

whenever

I

wanted,

and

I

could

showoff

my

colored

hair,

my

wedding

ring

and

other

stuff.

Now

I

understand

how

playful

and

childish

I

was

thinking”.p9

Quotation

19

“I

thought

having

a

baby

is

very

simple,

I

did

not

think

it

is

hard.

I

did

not

think

of

childbirth

and

I

was

just

thinking

of

having

a

baby”.p16

Quotation

20

“I

did

not

want

to

become

pregnant.

I

was

using

contraception

but

I

got

pregnant.

I

did

not

think

that

getting

pregnant

happened

so

easily.

I

did

not

know

how

I

can

be

pregnant.

I

wanted

to

do

something

in

order

not

to

get

pregnant.

I

had

heard

there

were

ways

to

prevent

or

quit

pregnancy

but

did

not

know

them

very

well”.p13

In

Iranian

culture,

being

a

mother

is

a

predictable

and

ordinary

event

that

happens

after

marriage

and

the

reasons

for

early

motherhood

lay

in

early

marriage.

The

minimum

legal

age

of

marriage

in

Iran

is

13

for

girls

and

15

for

boys,

but

there

is

no

legal

impediment

to

early

marriage(6).

Due

to

lack

of

laws

or

their

implementation,

there

is

no

possibility

to

protect

the

girls

from

early

marriage

in

many

countries

(18,

25,

27).

In

Iranian

culture,

women

are

expected

to

get

pregnant

as

soon

as

they

get

married,

and

if

this

does

not

happen,

people

would

assume

there

exists

a

problem

and

women

should

provide

an

explanation.

Early

marriage

and

motherhood

of

the

participants

was

in

response

to

external

and

internal

instincts.

A

poor

economic

condition

was

among

the

causes

of

early

marriage.

Several

studies

indicated

that

poverty

is

one

of

the

main

causes

of

early

marriage

which

is

a

survival

strategy

for

cutting

the

costs

for

poor

families

(3,

4,

6,

7,

18-20,

22,

25,

28,

29).

Family

breakdown

was

another

incentive

for

early

marriage.

In

Iran,

offspring

are

highly

dependent

on

family

and

the

existence

of

parents

who

have

special

roles

and

responsibilities

is

essential.

Divorce

or

death

of

a

parent

can

change

the

normal

process

of

family

life.

Coyne

(2014)

recognized

the

breakdown

of

family

structure

and

the

absence

of

the

father

as

the

reasons

for

early

marriage

and

motherhood(24).

A

group

of

adolescents

were

married

due

to

the

urge

of

their

parents

and

relatives.

Such

a

situation

occurs

mainly

in

traditional

families.

UNICEF

identifies

the

most

important

reasons

for

early

marriage

as;

the

urge

of

parents,

the

need

for

self-esteem

and

social

approval,

relatives’

pressure;

preventing

social

stigma,

staying

unmarried

in

girls,

and

sex

before

marriage(3,

20).

In

Iranian

culture,

the

most

important

reasons

for

parents’

tendency

towards

early

marriage

of

their

daughters

include;

protect

the

girl

and

ensure

her

purity,

security

and

safety.

Of

course,

this

is

the

parent’s

view

and

daughters

may

not

agree.

Worry

of

some

parents

from

harassment

has

caused

them

to

be

interested

in

early

marriage

of

their

daughters.

Most

of

the

daughters

in

traditional

Iranian

culture

accept

decisions

of

parents

without

any

disagreement.

Thus

sometimes

parents

don’t

consider

desires

of

adolescents.

Early

marriage

in

many

cultures

is

a

way

to

avoid

sin

and

sexual

promiscuity

(without

legal

marriage)(19).

In

these

cultures,

unmarried

girl’s

sex

is

an

odious

sin

and

creates

severe

social

stigma

for

family.

The

Muslims

of

Iran

believe,

marriage

is

the

best

way

to

meet

the

sexual

needs

even

when

a

girl

and

boy

are

very

young.

In

Islamic

countries,

because

of

religious

beliefs

in

favor

of

early

marriage

and

fear

of

pregnancy

outside

the

marriage,

parents

agree

with

the

marriage

of

their

daughters

at

first

opportunity(20,

22).

Some

adolescents

decided

to

get

pregnant

to

meet

the

demands

of

the

relatives,

especially

the

husband

and

his

family.

In

Iranian

culture,

having

children

is

fundamental

and

preservative

of

marital

life

and

couples

have

children

to

strengthen

the

relationship

between

themselves

and

their

families.

Kibretb

(2014)

stated

that,

one

of

the

reasons

for

motherhood

among

adolescents

is

to

help

strengthen

family

relationships(4).

Some

adolescents

were

married

to

be

like

their

families

or

friends.

Netsanet

(2015)

believes

that,

early

marriage

of

mother

increases

the

likelihood

of

her

daughter

to

copy

her(3).

Most

mothers

prefer

their

daughters

to

get

married

at

the

same

age

as

they

did(7).

This

kind

of

mothers

inculcate

to

their

children

that

early

marriage

is

a

social

value.

Adolescents’

tendency

to

emulate

peers

is

also

another

reason

for

this

copying

behavior(30).

Also,

the

media

encourage

adolescents

to

sexual

relations.

Some

of

the

adolescents

were

married

to

avoid

losing

the

position.

One

of

the

social

issues

affecting

early

marriage

is

the

fear

of

not

finding

a

suitable

partner.

This

belief

exists

in

traditional

Iranian

culture,

especially

in

rural

areas.

In

some

provinces

of

Iran,

adolescent

girls

have

the

best

suitors

for

marriage

because

the

best

men

tend

to

marry

girls

who

are

at

the

peak

of

beauty.

When

the

age

of

a

girl

increases,

her

opportunities

for

marriage

diminish.

Hence,

families

prefer

early

marriage

of

girls

to

prevent

this

problem.

In

some

other

cultures,

any

delay

in

marriage

makes

them

believe

that

the

girl

does

not

have

many

options,

so

the

girls

get

married

when

they

have

their

first

suitable

opportunity(3).

From

the

Muslims’

point

of

view

(including

Iranians)

some

events

are

divine

destinies,

and

will

happen

whether

we

want

them

or

not,

so

must

accept

them.

Marriage

in

adolescents

was

considered

as

such

an

event.

In

Iranian

culture,

there

is

this

belief

that

marriage

will

happen,

if

God

will.

So

the

marriage

time

is

at

“hands

of

God”.

Existing

religious

beliefs

of

the

society

had

caused

adolescent

mothers

to

see

children

as

the

reason

for

receiving

God’s

blessing.

They

believed

that,

having

children

would

make

their

life

better

so

they

had

decided

to

get

pregnant.

Iranians

believe,

when

a

child

is

born,

he/she

brings

many

gifts

for

the

family,

and

God

paid

more

attention

to

family.

Most

adolescents

believed

they

had

enough

physical

preparation

for

marriage,

and

did

not

pay

attention

to

mental

social,

financial,

and

spiritual

preparation

that

are

essential

for

marriage

and

making

a

family.

Rapid

physical

growth

during

adolescence

created

the

impression

that

they

were

prepared

for

marriage.

Early

marriage

also

is

more

common

in

adolescents

who

feel

the

emotional

readiness

for

marriage.

They

believe

they

should

offer

their

love

and

affection

to

another

human(19).

In

Iran,

marriage

is

legal

and

religious

way

of

expressing

love

and

Iranian

culture

supports

adolescents

who

married

to

achieve

love.

A

group

of

adolescents

were

married

to

meet

their

inner

needs

and

desires.

Adolescents

at

this

age

are

full

of

emotional

instability

and

become

interested

in

early

marriage

to

get

love

and

affection(19).

Another

encouraging

factor

for

early

marriage

was

gaining

independence.

Interference

of

people,

especially

parents

were

unpleasant

for

some

adolescents,

so

they

preferred

getting

married

than

obeying

their

parents.

Being

interested

in

having

children

and

responding

to

inner

desires

such

as

getting

rid

of

loneliness

was

causing

adolescent

mothers

to

get

pregnant.

Some

of

the

reasons

that

influence

adolescents

decision

about

pregnancy

which

included;

an

interest

in

having

children,

growing

up

(responsible,

mature,

independent),

receiving

love

of

the

husband

and

getting

rid

of

loneliness,

having

a

sense

of

ownership

(

having

a

child)

and

increasing

self-confidence

(being

a

good

mother)(31).

Some

of

the

adolescent

mothers

believed

that,

early

motherhood

depended

on

the

energy

and

strength

of

the

mother

and

having

a

small

age

gap

with

children

can

be

beneficial

for

both

mother

and

children.

Some

others

thought

marriage

was

simple.

Lack

of

sufficient

information

about

the

consequences

of

early

marriage

and

suitable

age

for

marriage

had

caused

adolescents

to

believe

marriage

is

simple(7,

29).

Insufficient

knowledge

of

adolescents

about

pregnancy,

childbirth,

and

childrearing

had

also

caused

them

to

assume

having

children

is

a

simple

process,

and

they

decided

be

pregnant.

More

participants

in

this

study

had

been

pregnant

unintentionally.

Majority

of

adolescents

did

not

have

adequate

information

about

sex

and

pregnancy

mechanism,

and

were

using

contraception

incorrectly

or

did

not

have

access

to

it

(15,

16,

32,

33).

Married

adolescents

are

forced

to

have

sex

under

the

pressure

of

spouse,

family

and

community

that

will

ultimately

lead

to

pregnancy(33,

34).

In

Iranian

culture,

married

women

must

be

engaged

in

sex

and

married

teens

are

also

not

excluded

from

this

law.

In

issue

of

early

marriage

and

motherhood,

the

youth,

mass

media,

schools,

neighbors,

religious

centers,

parents,

researchers,

health

centers,

and

policy

makers

must

be

considered.

Health

providers

can

improve

families’

economy

by

introducing

them

to

support

centers.

They

could

also

help

family

disputes

by

providing

appropriate

counseling

and

advice.

Providing

appropriate

education

for

adolescents,

parents

and

other

people

involved

can

lead

to

appropriate

and

timely

marriage.

Identifying

adolescent

mothers’

educational

and

caring

needs

and

providing

appropriate

training

and

care

can

prevent

unwanted

pregnancy

and

its

consequences.

School

nurses

can

use

the

influence

of

friends

to

promote

optimum

health

behaviors

in

adolescents.

All

of

these

services

must

be

done

in

accordance

with

the

principles

of

counseling

adolescents,

in

order

to

empower

them

in

decision

making

and

solving

challenges.

However,

the

sample

size

of

this

study

was

small

and

looked

at

only

part

of

multiple

cultures

Iranian,

so

researchers

suggest

the

need

for

similar

research

in

the

field.

The

findings

of

this

study

showed

that,

decision

for

marriage

and

early

motherhood

is

influenced

by

adolescents’

external

motivations

(related

to

society

and

life

situations)

and

internal

motivations.

Exploring

the

cultural

context

of

different

societies

can

guide

healthcare

policymakers

in

identifying

high-risk

groups

and

predict

the

consequences

of

this

phenomenon

with

respect

to

different

cultures’

view,

because

achieving

optimum

health

of

mothers

and

child

requires

close

examination

of

factors

affecting

marriage

and

motherhood.

Adolescents,

parents,

teachers,

and

other

influential

people

should

be

trained

on

the

negative

consequences

of

early

marriage

and

motherhood.

Health

policymakers

in

Iran

and

other

countries

should

protect

girls

against

early

marriage

and

motherhood,

because

adolescents

need

sufficient

time

to

properly

grow,

and

for

development,

and

success.

Acknowledgements

We

wish

to

thank

all

the

adolescents

who

participated

in

this

study

1.

Kamal

SM,

Hassan

CH,

Alam

GM,

Ying

Y.

Child

marriage

in

Bangladesh:

trends

and

determinants.

Journal

of

biosocial

science.

2015;47(01):120-39.

2.

Sumon

MNK.

Differentials

and

Determinants

of

Early

Marriage

and

Child

Bearing:

A

study

of

the

Northern

Region

of

Bangladesh.

Int

j

sci

footpr.

2014;2(1):52-65.

3.

Netsanet

T.

The

Causes,

Current

Situation

and

Socio-economic

Consequences

of

Early

Marriage:

The

Case

Of

Nyagatom

Community:

AAU;

2015.

4.

Kibretb

GD.

Determinants

Of

Early

Marriage

Among

Female

Children

In

Sinan

District,

Northwest

Ethiopia.

Health

Science

Journal.

2015;9(6):1-7.

5.

Psaki

SR.

Addressing

early

marriage

and

adolescent

pregnancy

as

a

barrier

to

gender

parity

and

equality

in

education.

Background

Paper

for

EFA

Global

Monitoring

Report.

2015.

6.

Montazeri

S,

Gharacheh

M,

Mohammadi

N,

Alaghband

Rad

J,

Eftekhar

Ardabili

H.

Determinants

of

Early

Marriage

from

Married

Girls’

Perspectives

in

Iranian

Setting:

A

Qualitative

Study.

Journal

of

environmental

and

public

health.

2016;2016.

7.

Matlabi

H,

Rasouli

A,

Behtash

HH,

Dastjerd

AF,

Khazemi

B.

Factors

responsible

for

early

and

forced

marriage

in

Iran.

Science

Journal

of

Public

Health.

2013;1(5):227-9.

8.

Pogoy

AM,

Verzosa

R,

Coming

NS,

Agustino

RG.

Lived

Experiences

Of

Early

Pregnancy

Among

Teenagers:

A

Phenomenological

Study.

European

Scientific

Journal.

2014;10(2):157-69.

9.

Gyesaw

NYK,

Ankomah

A.

Experiences

of

pregnancy

and

motherhood

among

teenage

mothers

in

a

suburb

of

Accra,

Ghana:

a

qualitative

study.

International

journal

of

women’s

health.

2013;5:773-80.

10.

worldbank.

Adolescent

fertility

rate

2016.

Available

from:

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sp.ado.tfrt.

11.

Pitso

T,

Kheswa

J.

The

Vicious

Cycle

of

Teenage

Motherhood:

A

case

study

in

Eastern

Cape,

South

Africa.

Mediterranean

Journal

of

Social

Sciences.

2014;5(10):536-40.

12.

Riva

Crugnola

C,

Ierardi

E,

Gazzotti

S,

Albizzati

A.

Motherhood

in

adolescent

mothers:

Maternal

attachment,

mother–infant

styles

of

interaction

and

emotion

regulation

at

three

months.

Infant

Behavior

and

Development.

2014;37(1):44-56.

13.

Monstad

K,

Propper

C,

Salvanes

KG.

Is

teenage

motherhood

contagious?

Evidence

from

a

Natural

Experiment.

Nowegian

School

of

Economics,

Department

of

Economics:

2011

0804-6824.

14.

Sarreira

de

Oliveira

P,

Néné

M.

Nursing

care

needs

in

the

postpartum

period

of

adolescent

mothers:

systematic

review.

Journal

of

Nursing

UFPE

on

line

[JNUOL/DOI:

105205/01012007].

2014;8(11):3953-61.

15.

Rahman

MM,

Goni

MA,

Akhter

MR.

Correlates

of

early

motherhood

in

slum

areas

of

Rajshahi

City,

Bangladesh.

Avicenna.

2013;6:1-5.

16.

Diaconescu

S,

Ciuhodaru

T,

Cazacu

C,

Sztankovszky

L-Z,

Kantor

C,

Iorga

M.

Teenage

Mothers,

an

Increasing

Social

Phenomenon

in

Romania.

Causes,

Consequences

and

Solutions.

Revista

de

Cercetare

si

Interventie

Sociala.

2015;51:162-75.

17.

Malhotra

A.

The

Causes,

Consequences

and

Solutions

to

Forced

Child

Marriage

in

the

Developing

World.

International

Center

for

Research

on

Women

(ICRW)

US

House

of

Representatives

Human

Rights

Commission,

Washington

DC.

2010;15:1-12.

18.

Okonofua

F.

Prevention

of

Child

Marriage

and

Teenage

Pregnancy

in

Africa:

Need

for

more

Research

and

Innovation/Il

faut

encore

plus

de

recherche

et

d’innovation

dans

la

prévention

de

la

grossesse

chez

les

enfants

et

les

adolescentes

dans

les

mariages

africains.

African

Journal

of

Reproductive

Health/La

Revue

Africaine

de

la

Santé

Reproductive.

2013;17(4):9-13.

19.

Hejazziey

D.

The

Relationship

between

Adolescent

Development

and

Marriage

in

Cirendeu

Village,

District

East

Ciputat,

South

Tangerang,

Banten

Province

of

Indonesia.

International

Journal

of

Psychological

Studies.

2016;8(1):162-77.

20.

Jain

G,

Bisen

V,

Singh

S,

Jain

P.

Early

marriage

of

girls

as

a

barrier

to

their

education.

International

Journal

of

Advanced

Engineering

Technology.

2011;2(3):193-8.

21.

Mahato

SK,

Dhakal

RK.

Causes

and

Consequences

of

Child

Marriage:

A

Perspective

International

Journal

Of

Scientific

&

Engineering

Research.

2015;7(7):698-702.

22.

Ezeah

P.

Marriage

and

motherhood:

a

study

of

the

reproductive

health

status

and

needs

of

married

adolescent

girls

in

Nsukka,

Nigeria.

Journal

of

Sociology

and

Social

Anthropology.

2012;3:1-6.

23.

Shrestha

A.

Teenage

pregnancy

in

Nepal:

consequences,

causes

and

policy

recommendations.

48th

International

Course

on

Health

Development;

Vrije

Universiteit

Amsterdam:

KIT

(Royal

Tropical

Institute)

Development,

Policy

and

Practice;

2012.

24.

Coyne

CA.

Quasi-experimental

approaches

to

understanding

the

causes

and

consequences

of

teenage

childbirth:

Indiana

University;

2014.

25.

Mulchandani

LI.

Determinants

of

Child

Marriage.

International

Indexed

&Referred

Research

Journal.

2012;3(32):13-4.

26.

Elo

S,

Kyngäs

H.

The

qualitative

content

analysis

process.

Journal

of

advanced

nursing.

2008;62(1):107-15.

27.

Sibanda

T,

Mudhovozi

P.

Becoming

a

Single

Teenage

Mother:

A

Vicious

Cycle.

J

Soc

Sci.

2012;32(3):321-34.

28.

Sabbe

A,

Oulami

H,

Zekraoui

W,

Hikmat

H,

Temmerman

M,

Leye

E.

Determinants

of

child

and

forced

marriage

in

Morocco:

stakeholder

perspectives

on

health,

policies

and

human

rights.

BMC

international

health

and

human

rights.

2013;13(1):43-56.

29.

Khanam

K,

Laskar

BI.

Causes

and

Consequences

of

Child

Marriage–A

Study

of

Milannagar

Shantipur

Village

in

Goalpara

District.

International

Journal

of

Interdisciplinary

Research

in

Science

Society

and

Culture(IJIRSSC).

2015;1(2):100-9.

30.

Kapinos

KA,

Yakusheva

O.

Long-Term

Effect

of

Exposure

to

a

Friend’s

Adolescent

Childbirth

on

Fertility,

Education,

and

Earnings.

Journal

of

Adolescent

Health.

2016;59(3):311-7.

e2.

31.

Butler

K,

Winkworth

G,

McArthur

M,

Smyth

J.

Experiences

and

Aspirations

of

Younger

Mothers.

Institute

of

Child

Protection

Studies,

Australian

Catholic

University,

Canberra.

2010.

32.

Mothiba

TM,

Maputle

MS.

Factors

contributing

to

teenage

pregnancy

in

the

Capricorn

district

of

the

Limpopo

Province.

curationis.

2012;35(1):1-5.

33.

Alenkhe

OA,

Akaba

J.

Teenage

pregnancy

in

Benin

City:

Causes

and

Consequences

for

Future

National

Leaders.

International

Journal

of

Social

Sciences

and

Humanities

Review.

2013;4(2):33-41.

34.

Kalamar

AM,

Lee-Rife

S,

Hindin

MJ.

Interventions

to

prevent

child

marriage

among

young

people

in

low-and

middle-income

countries:

a

systematic

review

of

the

published

and

gray

literature.

Journal

of

Adolescent

Health.

2016;59(3):S16-S21.

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|